Catalunya, Catalunya

Regional Planning and Regional Politics

If architects were the only voters, Pasqual Maragall would carry the day completely. Indeed, as far as fostering the quality of architecture is concerned, few politicians have as distinguished a service record as Barcelona’s former mayor. Under his mandate the city acquired a degree of world prestige that has few precedents, and the Olympic Barcelona of urban planning and design became a Mecca of architectural tourism. When the Royal Institute of British Architects awarded its gold medal to Barcelona (its first time, in more than a hundred years of existence, not to honor an individual, but a city), the only issue debated on by the jury was whether to personalize the prize in Maragall or, as things eventually turned out, in all the mayors and urban planners of the city’s recent past. And so it was that when Maragall decided to run in the Catalan regional elections, numerous architects sought to help fund the campaign by donating drawings and sketches for auction.

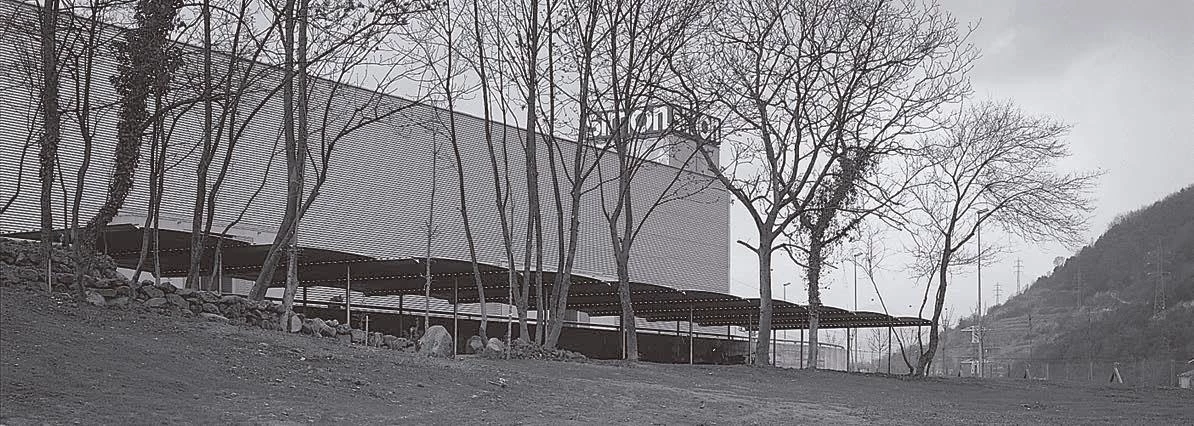

The Simón warehouse in Olot (above) and the Barcelona Botanical Garden (below) show how modernization can be reconciled with visual quality in the environment.

Curiously, Maragall’s cosmopolitan passion for architecture is censured by partisans of Jordi Pujol, who dismiss the ex-mayor as a candidate of design, too much a snob and too much a traveler. Pujol’s page on the Internet invites one to search Pasqui in Rome or New York, France or Madrid, anywhere outside the rich oasis of Catalonia, and attributes to him a deep ignorance of the region, while “de ciutats guais i dissenyades en sé més que el Mariscal.” But such lambasting of Maragall’s association with the mascot Cobi is hardly convincing, coming from a president who, feeling left out of the Olympic spotlight, himself tried to create an electoral platform through the populist adventure of Port Aventura, a theme park that opened with mountain climber Pujol and his parachutist wife Ferrusola braving the Dragon Khan roller coaster. The experience had its share of frights, as those caused by the corruption scandal of Javier de la Rosa when the place was still called Tibigardens, but did set the rule that no self-respecting regional president can carry on without building a theme park of his own, and Pujol’s counterparts elsewhere in Spain followed suit: Chaves with Isla Mágica, Zaplana with Terra Mítica, Gallardón with Warner’s Hollywood at San Martín, Bono with the Ciudad de los Bosques in Toledo and the Reino de Don Quijote in Ciudad Real, and even Rodríguez Ibarra with the ‘cultural park’ of Emérita Viva.

In the end Pujol has beaten them all, with the subsequent entry of Universal Studios in Port Aven-tura consolidating the Tarragona amusement center’s position as the Parisian Disneyland’s main competitor in Europe, not to mention that Catalonia also boasts the planet’s most unique dispersed theme park, the Daliland triangle formed by Figueras, Púbol and Port-Lligat. Pujol, who has that certain Dalinian cheek in his expression and a rather surreal air in his public appearances, occasionally defends an idea of Catalonia that in caricature resembles a theme park of itself. Halfway between the ethnic reserve that Albert Boadella satirized in his play M-7 Catalonia and a hypothetical Catalan version of the island of national essences that Julian Barnes describes in his novel England, England, Catalonia has reconciled cultural nationalism with the gluttony of many town councilors, and this non sancto marriage between recreational nationalism (Savater dixit) and real estate has degraded the landscape to extremes that can only offend those who truly love Catalonia.

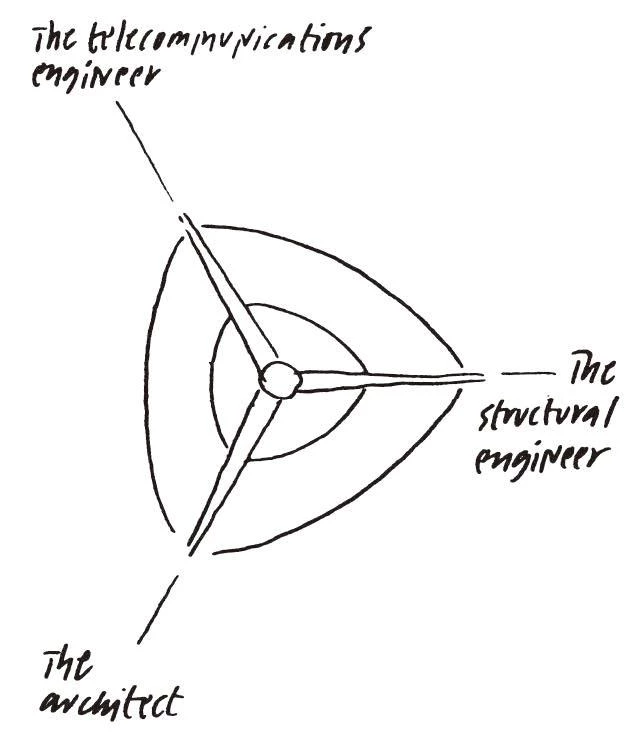

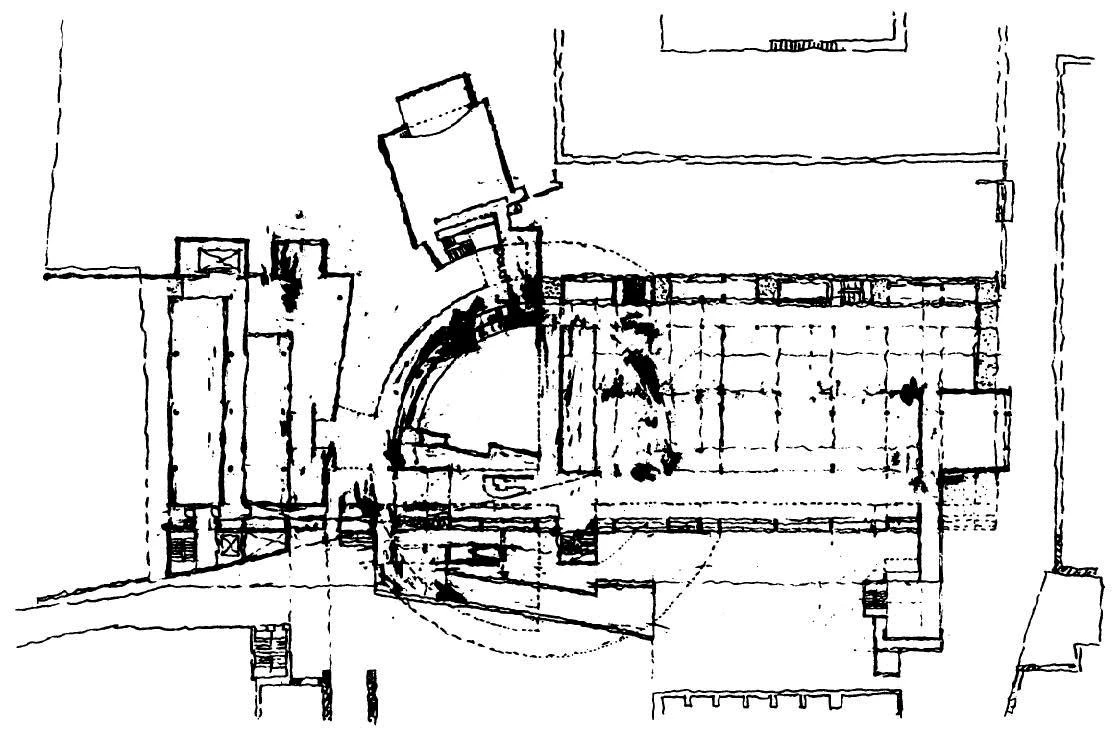

The only building by British architect Norman Foster to be designed for Barcelona, the Collserola Communications Tower was incorporated into the city’s skyline at the time of the Olympic Games held in 1992.

In the recent ceremony of the Generalitat’s National Prize for Cultural Heritage, which for the first time was awarded to a newly constructed building, Lluís Clotet and Ignacio Paricio’s Simón plant at Olot, a much dismayed Pujol had to hear out the architects lamenting the territorial deterioration that is spoiling Catalonia, while the author of the new Liceo, architect and critic Ignasi de Solà-Morales, has publicly deplored ‘catastrophic urbanism’ and the erosion of the landscape that the ‘abominable’ valley of Llobregat exemplifies. This is certainly not what one would have expected of a policy of communal sensibility that has its emotional identity in the rural areas, much less when Maragall had already shown, in the city of Barcelona, how economic modernization and liberal attitudes are not necessarily at odds with visual quality in the environment – as recently proven by the completion of a late but exquisite aftereffect of the Olympic fervor, Carlos Ferrater’s Botanical Garden. In the comparison between Baltimore and Bavaria, it must be pointed out that the ex-mayor has translated his admiration for North America better than the president has done his sympathy for Bavarian capitalism.

Nevertheless it would be excessive to set an Olympic Maragall against a thematic Pujol, and in Catalonia there is no Galician-style conflict between urban and rural politicians of the kind Rajoy and Cuiña are engaging in to succeed Manuel Fraga. The undeniably formidable stature of both candidates puts the debate on a higher plane, dignifying political activity and increasing the admiration that the majority of Spaniards feels for Catalonia. Once the lucid sarcasm of Vidal-Quadras was sacrified on the expiatory altar of the last investiture, neither mockery of Pujol’s mercantilistic complaints nor skepticism about Maragall’s third way can negate the fact that these two political animals have swept all second-raters off the stage, to fight a one-on-one that makes us once again enjoy politics as an intelligent spectacle.

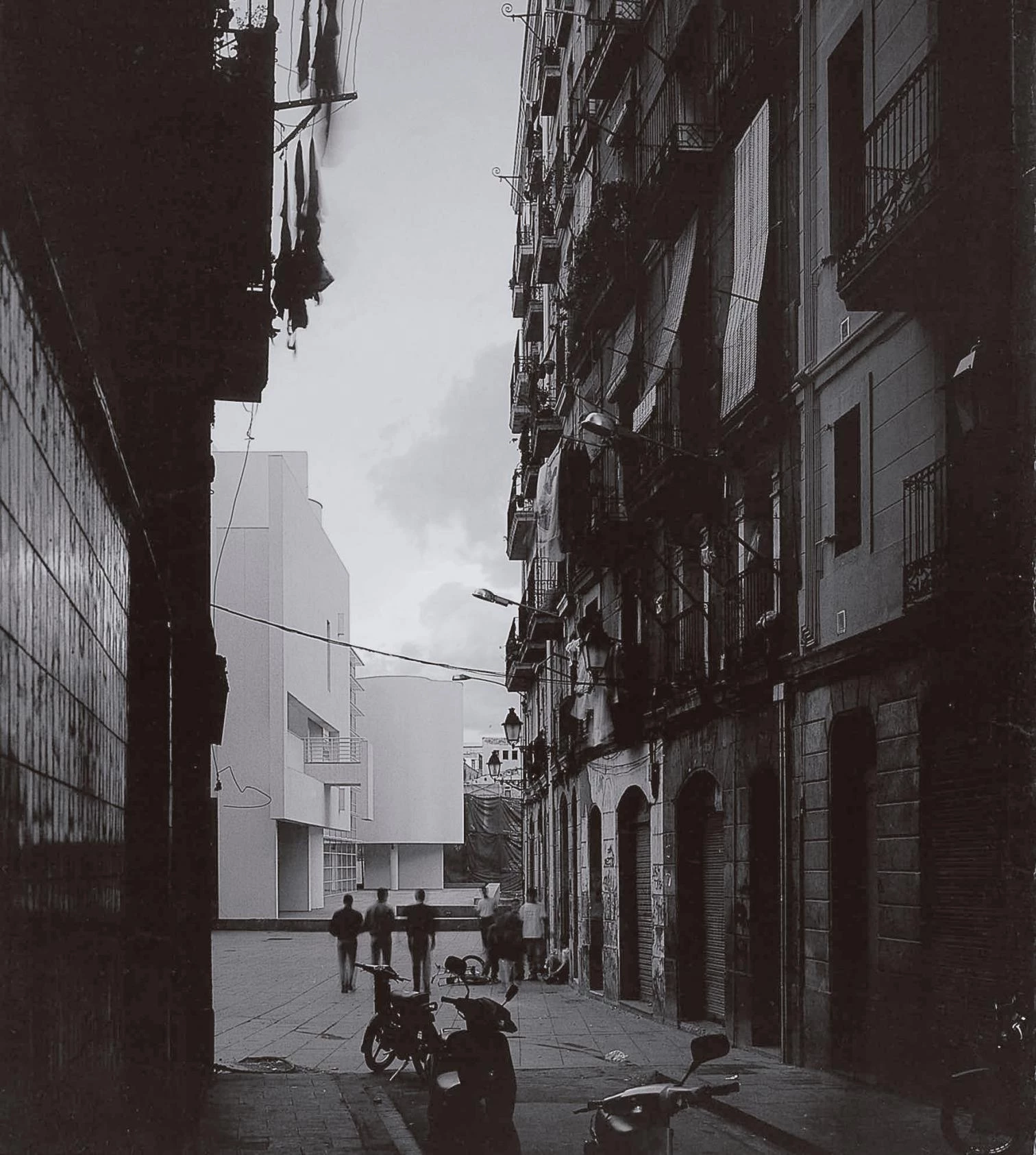

Author of the Barcelona Museum of Contemporary Art, Richard Meier is one of the five winners of the Pritzker Prize who donated his drawings in order to finance Pascual Maragall’s campaign for president of Catalonia.

The Vote of Architects

Maragall’s American electoral methods have led him to seek financial help from intellectual and artistic elites. Architects donated drawings to the campaign and, along with artists’ works, these were displayed and auctioned in events called ‘Art pel canvi’. With signatures like Arroyo, Gordillo, Lam, Matta or Tàpies, the list of painters is dignified. But the roster of architects who through drawings have supported the city’s ex-mayor in his bid for a place in regional government, is extraordinary. Besides the expected presence of the entire Catalan crème de la crème, led by Bohigas, Tusquets and Miralles and a representation from Madrid headed by Moneo and Navarro Baldeweg, the collection of international names reads like a who’s who: the Americans Meier and Gehry; the Brits Foster, Grimshaw and Chipperfield; the Italians Venezia and Fuksas; the Portuguese Souto de Moura and Siza; and the French Perrault. Such an accumulation of talent – counting as many as five Pritzkers and including architects who have never built in Barcelona, and thus owe nothing to Maragall –makes one wonder instead about the absences: Bofill, Calatrava, Isozaki or Gregotti are names a candid glance would have expected to find here.