Three Feasts and a Funeral

Galicia, Catalonia and the Basque Country build mediatic, cosmopolitan buildings while Madrid remains intoxicated with folklore.

The promise and the risk of global culture have been expressed in Spain through three cosmopolitan feasts and a parochial funeral. The inauguration of the Domus in La Coruña, the Museum of Contemporary Art of Barcelona and the metro of Bilbao contrast with the sad paralysis of Madrid, humiliated by folklore and grandiloquence. While Galicia, Catalonia and the Basque Country endow themselves with international architectures, the capital drowns amid the rhetorical hypertrophy of museums and the proliferation of an urban furniture and civic statuary whose ridiculous archaism inspires both laughter and lamentation.

This culture of spectacle, which during the past decade has spread throughout the world, combines fervor for the foreign with devotion to the domestic, in variable proportions which do not exclude the nostalgia for the genuine that facsimiles and replicas express.

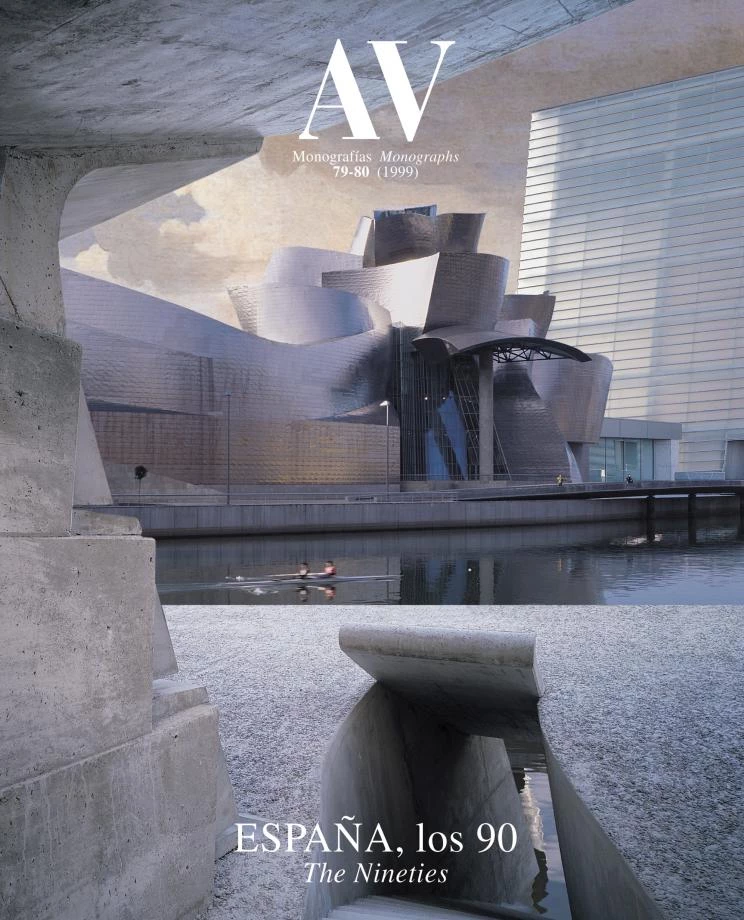

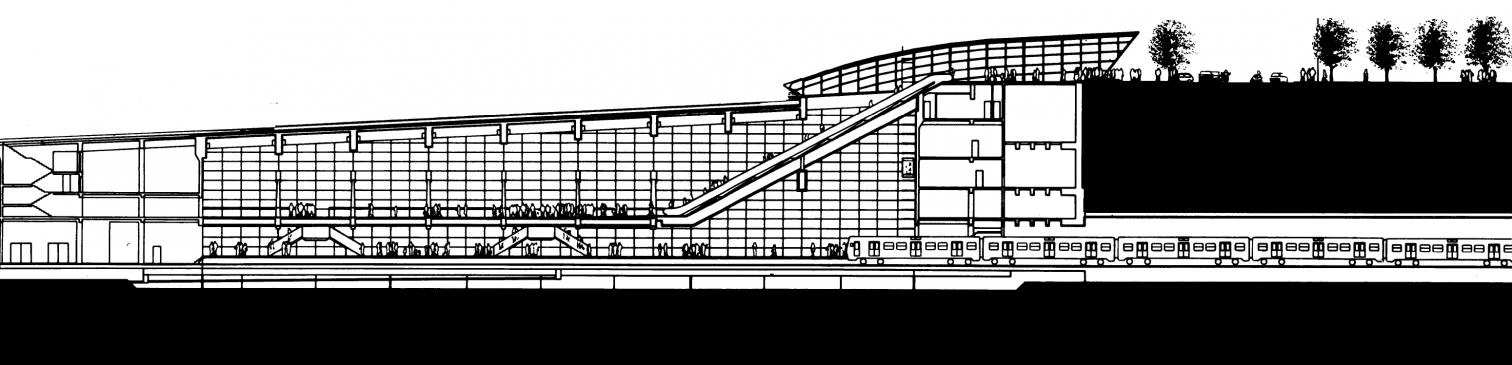

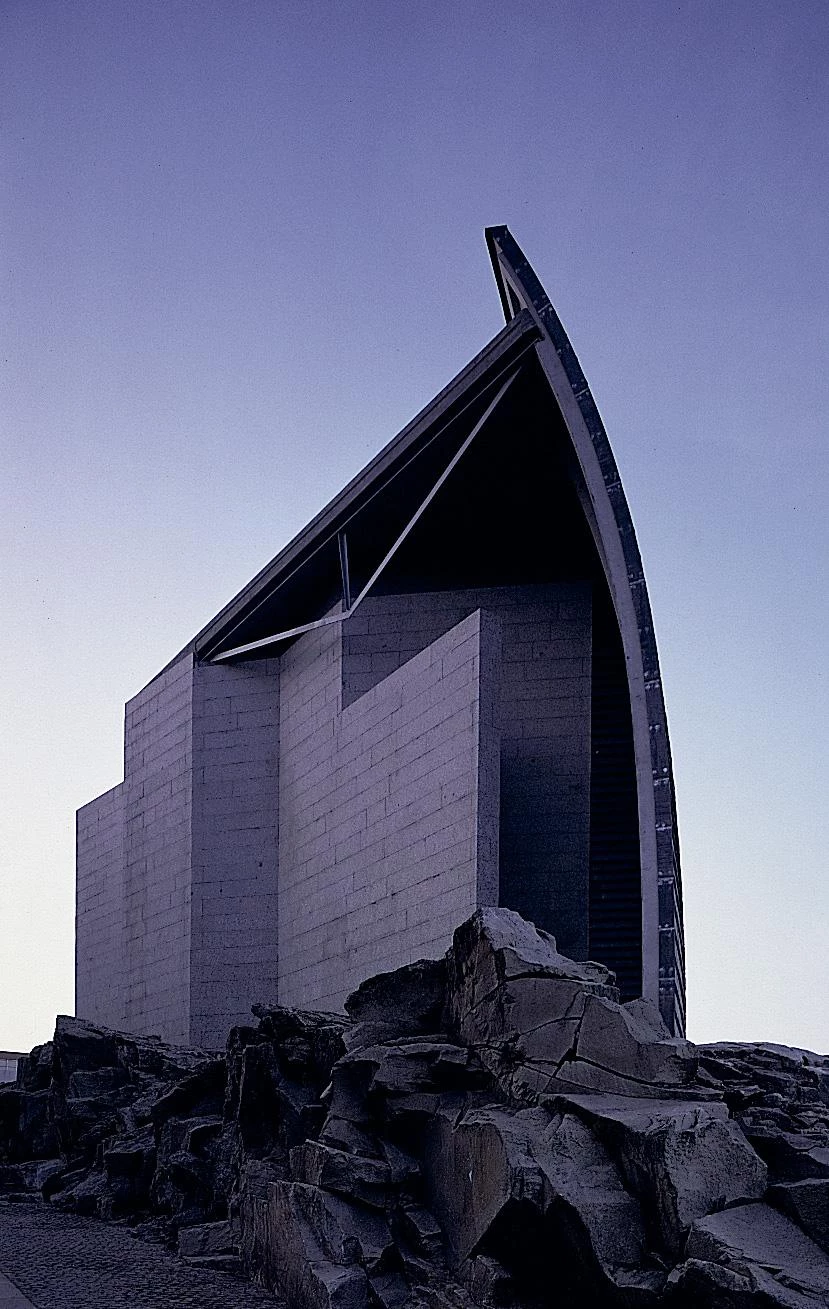

With the Metro by Foster in Bilbao (above), the Domus by Isozaki in La Coruña (center), and the MACBA by Meier in Barcelona (below), Spanish regions take part in the globalization of architecture.

Paradoxically, in Spain historical regionalisms have embraced architectural internationalism. Arata Isozaki in La Coruña, Richard Meier in Barcelona and Norman Foster in Bilbao express the opening of Spanish culture to Asian, American and European currents which are transforming a country fully immersed in the adventure and challenge of a planet-wide material and symbolic market.

In Galicia, the slate sail of Isozaki’s Domus has been the emblem of an architectural renewal that has had its centers in La Coruña – whose Museum of Fine Arts has been enlarged with painstaking subtlety by Manuel Gallego –and in Santiago, where the Galician Center of Contemporary Art, a work of the Portuguese Álvaro Siza, and pieces by the German Josef Paul Kleihues and the Italian Giorgio Grassi will soon be joined by more buildings by Isozaki and Siza, besides a communications tower by Foster.

In Barcelona, Meier’s luminous white museum in the old quarter has been the central piece of an urban regeneration that during the year also had significant moments in the opening of the commercial and recreational complex of Port Vell, designed by Piñón & Viaplana, and in the National Museum of Art of Catalonia, which already displays a collection of Romanesque apses at the Palau de Montjuïc, remodeled by the Italian Gae Aulenti.

In Bilbao, finally, the convulsions of Basque society have not hindered the culmination of the backbone of its urban regeneration, a metropolitan railway with stations designed with efficient elegance by Foster; a project to be complemented by a new airport, a work of Santiago Calatrava, and several large-scale cultural buildings, notably the Guggenheim Museum by the Californian Frank Gehry, whose sculptural frame already rises beside the Nervión.

This year such fertility in the periphery was haplessly counterbalanced in the peninsular center, where the capital’s misadventures were aggravated by two new episodes: a megalomaniac competition to transform the Prado into a citadel of museums, and the invasion of Madrid’s sidewalks by several thousand aberrantly designed publicity columns that ended up inciting a people’s demonstration against physical and visual pollution.

With Europe submerged in the unease and uncertainty of adapting to a world without economic frontiers, and Spain dispiritedly trapped in the twilight of a political period of material modernization and social disintegration, architecture finds itself at an unprecedentedly turbid crossroads in which our suspicion of a road’s end is as clear as our ignorance of the future path. As the Spanish philosopher Ortega y Gasset said at another critical point of our troubled history, we do not know what is happening to us and that is precisely what is happening to us.