Apocalytic and totemic in the face of mass urbanity: following the early Umberto Eco, such could be the dilemma of today’s architects. If the semiologist of our pop youth distinguished between the apocalyptics who fear mass culture and the integrated who submit to it, attitudes toward the contemporary city can also be polarized between those who judge the boundless urbanization of territories as an ecological and social tragedy, and those who join in on the real estate tide by raising signs of identity or force. The quarter of a million victims of the Boxing Day tsunami drew attention to the physical fragility of modern suburbanity with devastating emotional violence, and the hurricanes that whipped Louisiana and Texas – from the foretold destruction of New Orleans to the chaotic evacuation of Houston – have likewise shaken the smug self-confidence of the United States with frustration and panic, nourishing millenarian vertigos and mute apocalypses. In such a panorama of risk and uncertainty – accentuated by the natural calamities and the specter of climatic change, but previously opened in history and memory by 9-11 and its echoes, from Madrid’s 11-M to London’s 7-J – our stars of architecture are either crowning or commencing urban totems that turn their backs on the beat of the world, and we are at a loss as to how to take them, whether as arrogant icons of masculine affirmation before the tribulations of the times, or as vertical exorcisms pretending to keep vigil over the defenseless slumber of cities besieged by shadows.

El rascacielos propuesto por Santiago Calatrava para Chicago será el más alto de Estados Unidos.

A good interpreter of the tremors of our times is the geographer and professor Jared Diamond. Some years ago he explained the success of the West in Guns, Germs and Steel: the Fates of Human Societies, a Pulitzer Prize winner that sold a million copies. The sequel, Collapse: How Societies Choose to Fail or Succeed, addresses the other side of the coin, the reasons for the failure of some societies of the past, from the inhabitants of Easter Island to the Vikings of Greenland, which serve as an example and a warning for contemporary societies like China, the United States, or Australia whose current development shows the same features that led to the sinking of the former. Among these factors, the determinant for Diamond is the social response to environmental problems, and his persuasive description of the gradual collapse of collective life after the devastation of a fragile habitat – a consequence of social decisions that are more deliberate than inevitable – has produced the expectable impact on the anguished post-tsunami conscience, and one will have generate an even greater one at the settling of the perception of vulnerability that Katrina and Rita have brought to the heart of a country which, caught in the mire of an impossible war, suddenly finds itself defenseless as well in the face of climatic catastrophe: a political and technical crisis that joins with apocalyptic terrorism and the unfathomable mutations produced by science in our biological nature in building for us a nightmare future. Meanwhile, Diamond describes life in Los Angeles suburbs, protected by private police, where people drink bottled water, live on private pensions, and send their children to private schools – so that they do not much care about the deterioration of the police, water supply, social security, and public schools – and he wonders how long before the excluded begin to threaten the rich neighborhoods as in the past they attacked the palaces of Mayan kings or tore down the statues of Easter Island. No fence will keep out the poor, he says, and this is something he need not repeat to those of us who see the news coming from Melilla and Ceuta (the Spanish cities in northern Africa, frequently entered by illegal immigrants that climb the fence separating them from Morocco), from a border overwhelmed as much by assaults as by the colossal gradient of fertility and income.

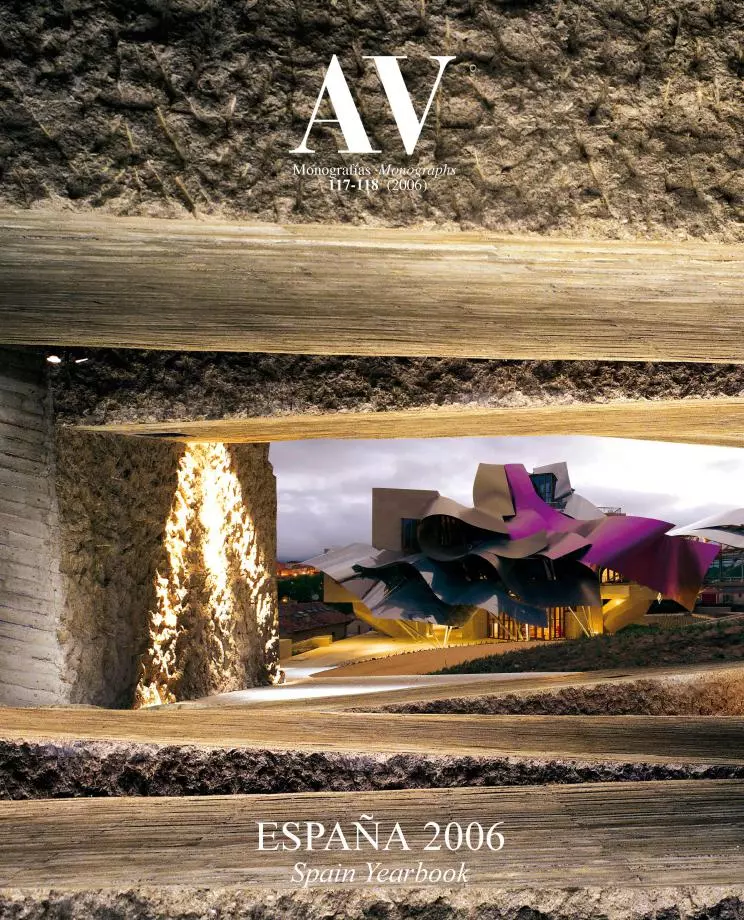

In this shaken planet, the leaders of architecture blindly compete with the social leaders, the former pursuing their narcissistic careers in the same way that the latter concern themselves only with the political or economic ruses that precariously keep the feeble building of an irresponsible nomenklatura on its feet. Take for example two figures whom the media frequently tag as artists and even geniuses, and who for different reasons have been making news of late. One is Santiago Calatrava, who in October opened a solo exhibition of his sculptures, drawings, and models in New York City’s Metropolitan Museum of Art; and inaugurated Valencia’s Palace of the Arts, a work as colossal and calligraphic as a Flash Gordon comic; who in September, in the company with Hillary Clinton, laid the first stone – or the first beam – of his bristling, lyrical transport hub in Ground Zero; who in August presented Malmö with a twisted skycraper that according to The Architect’s Newspaper makes its occupants dizzy; and who in July presented a twisting, Solomonic project – again in organic, mannerist torsion – to materialize in Chicago, cradle of the skyscraper, as the tallest building in the United States, in dialogue with the two local giants, the John Hancock and the Sears towers, so defying in its splendid location, right where the Chicago River meets Lake Michigan, and so disdainful of the security concerns triggered by 9-11 as to have elicited the censure of the developer Donald Trump: “No one in his right mind would put up a building that high in today’s horrible world. I don’t think it’s a real project. It’s all a joke”. Well, this same Calatrava who has made the headlines during 2005 is the butt of an anecdote printed in The New York Times which illustrates the self-referential character of contemporary architecture. According to Brian Carley, vice president of the Fordham Company, developer of the Chicago skyscraper that is to be called the Fordham Needle, the architect’s wife turned to him during a meeting in Zurich and said: “You know, Brian, whatever you call it, it’ll be known as the Calatrava”.

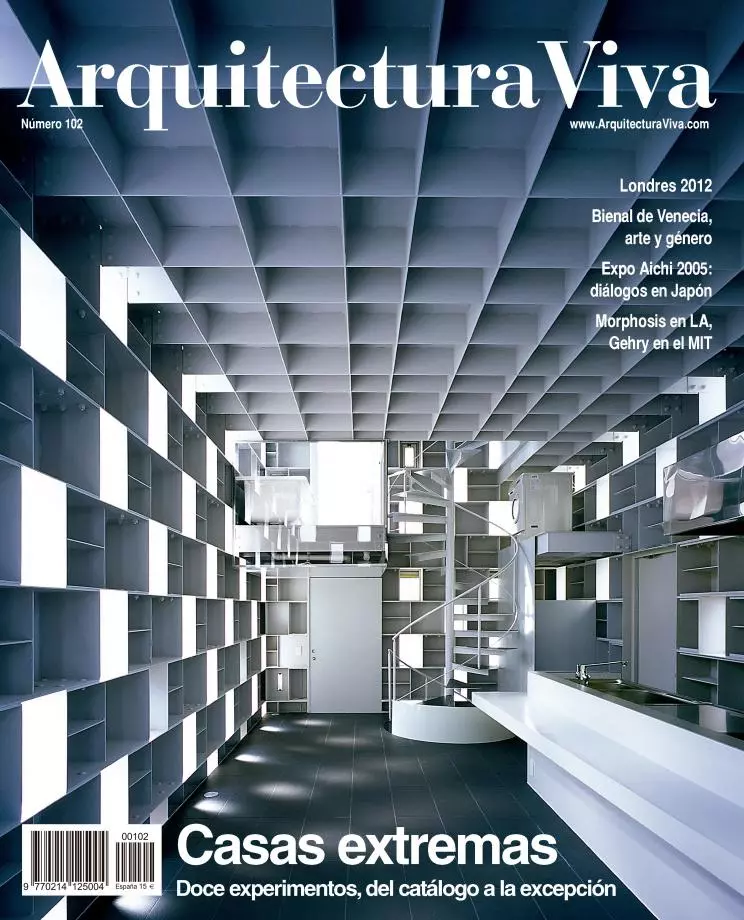

El nuevo icono urbano de Barcelona es la torre Agbar, construida por Jean Nouvel como un obús de hormigón perforado azarosamente y revestido con vidrios coloreados que cambian su aspecto en la noche.

Whether we like it or not, Robertina is right. And if the spectacular, resounding enlargement of the Reina Sofía Museum, opened in September, has been named after Nouvel, it is simply a recognition of the mediatic notoriety that now distinguishes star architects, celebrities competing in glitter with their public and private clients. In the Puerta América hotel, opened only a few days before, Nouvel has had to share the limelight with the motley cast of designer figures aboard, and this is the only reason why the building of colored canopies is not known by his name, but as ‘the hotel of the architects’ or ‘the hotel of the stars’, which only reinforces our argument. And in the Agbar tower, inaugurated by King Juan Carlos in the same month, the protagonism of the architect was so clamorous that El País did not hesitate to title the report “Nouvel’s tower, new totem of the Barcelona sky”. The royal was relegated to second place both typographically and photographically, as was the president of the company and of La Caixa bank, Ricard Fornesa, who described the building as “a gift to the city”. A gift from the company or from the architect? The extraordinary hype showered on the architect transpires in a context where the hostile takeover bid of Gas Natural (controlled by the Barcelona-based La Caixa) over Endesa, one of the largest electric companies in Spain – which affects corporate headquarters and the geographic localization of power over energy – agglutinates the country’s political and economic debate, a matter involving interests far more transcendental than the originality or the extravagance of a concrete shell randomly perforated with pixellated windows and capriciously colored beneath glazed blinds that sheath it like a fantasy condom. Gas Natural, too, has a main office of its own in the making, designed by the late Enric Miralles with the emblematic uniqueness that the firm wished to endow itself with in order to assert its implantation in Barcelona after the merging of Catalana de Gas and Gas Madrid, and after the acquisition of Enagás, the public distribution monopoly, that resulted from the parliamentary pacts made between the socialist government in Madrid and the Catalan nationalists in 1993.

But the great battles of territories for energy and water – which hardly dissimulate the aesthetic fencing of the guest artists – are fought in the common field of an unstoppable growth that undermines the environmental foundations of our very survival. The electric sparkle of our luminous landscapes does not dissipate the dark spots of the future. Blinded by the kilowatt, we forget Katrina and Kyoto. Architects raise illuminated totems, pretending to forget that priapism is an erectile dysfunction. At night in Sin City, its icons look like gods protecting us from the dark, but they are false idols that are impotent in the face of the catastrophe that hangs over the happy smug city. As the British historian Eileen Power once wrote, the Romans, blind to what was happening to them, spoke of Roma immortalis on the very eve of Rome’s fall.