Apple Park in Cupertino, California

Foster + Partners- Type Commercial / Office Headquarters / office

- Material Glass

- Date 2010 - 2017

- City Cupertino (California)

- Country United States

- Photograph Nigel Young Mikael Jansson DJI Phantom 4 Pro iMore Mark Mahaney

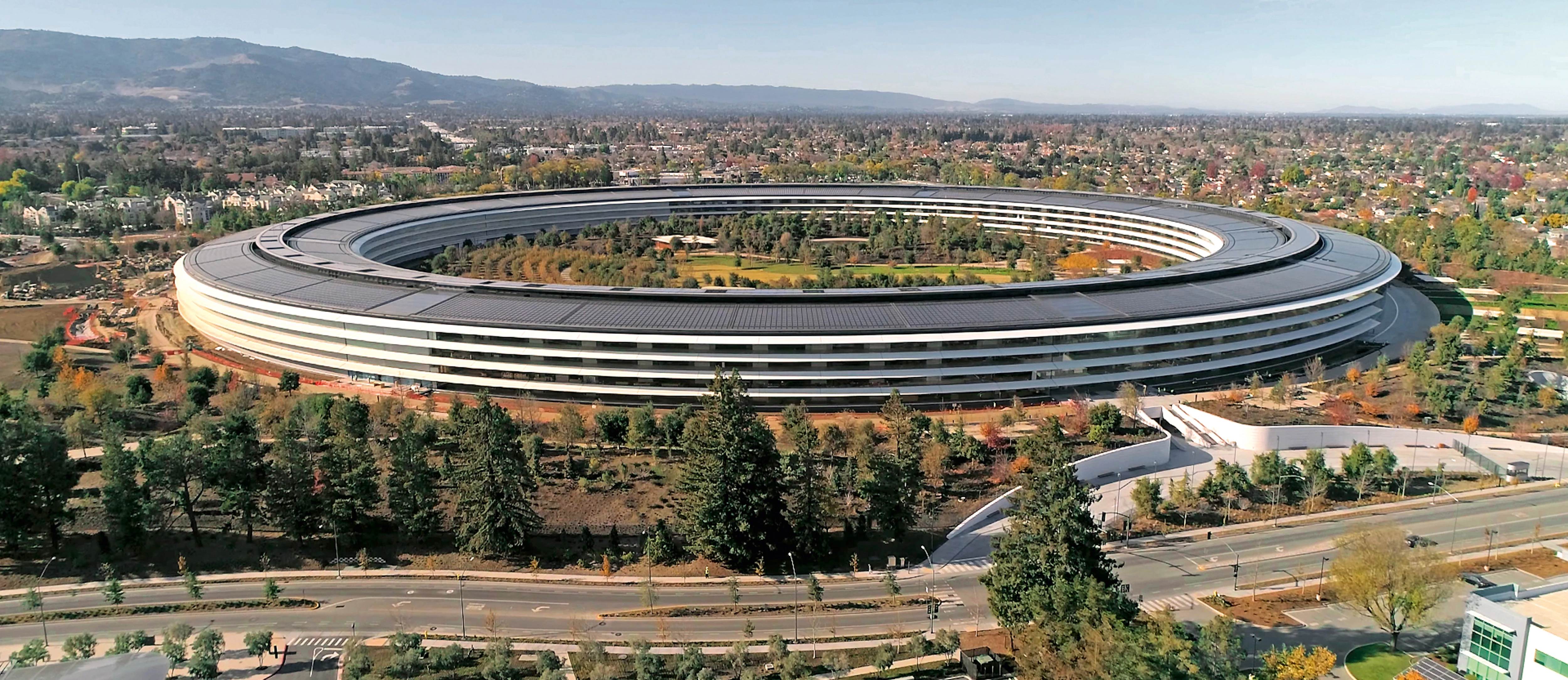

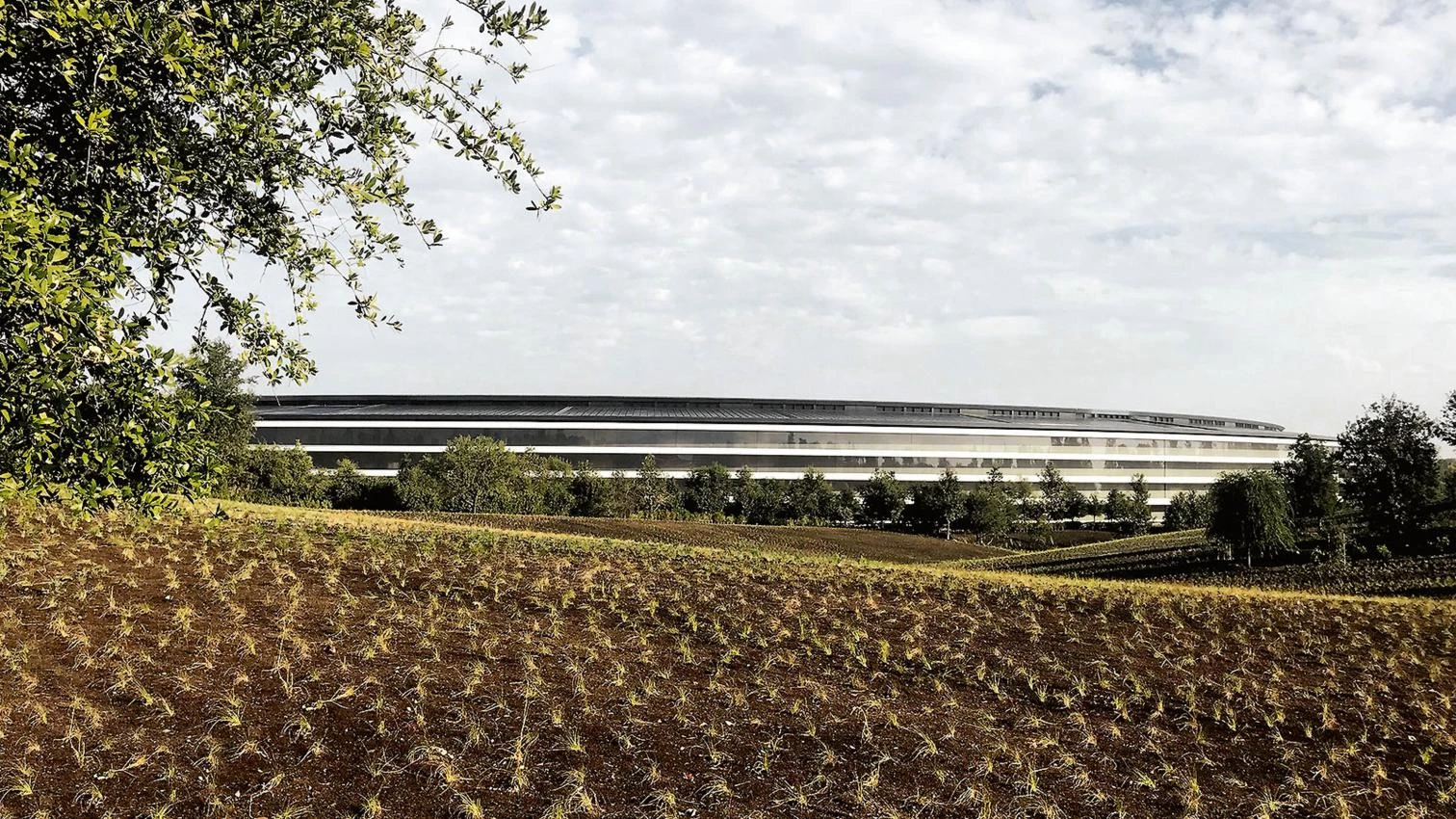

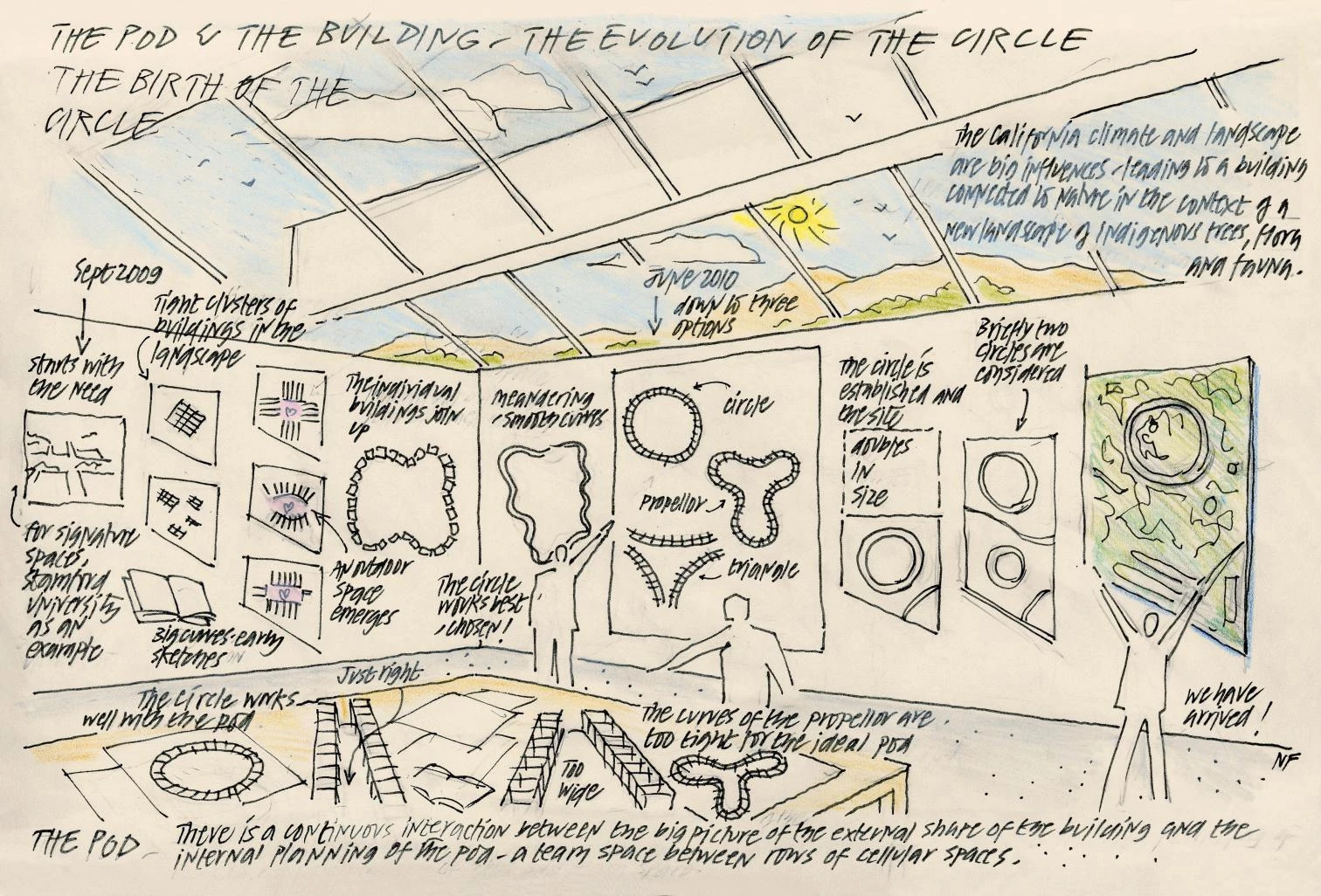

A circle is whole, continuous, unbroken, closed. Its shape implies completeness, a kind of unified perfection. Apple Park, Apple’s ring-shaped new headquarters designed by Foster + Partners, invites interpretation; it is a building and a symbol. Located in Cupertino, California, Apple Park is a 21st-century update of the mid-20th-century corporate office campus, enhanced with environmental sensitivity and an emphasis on employee wellness.

In most of the United States, the suburban corporate campus has fallen out of fashion as a business ideal. Many companies have returned at least part of their operations to central cities, locations that younger educated workers are believed to prefer. The technology companies of Silicon Valley, however, have largely bucked this trend with an ever-sprawling footprint, with all the ensuing environmental and social burdens that this entails. Apple’s grand investment in Cupertino cements its suburban identity, and by extension, the suburban Bay Area as the dominant landscape of the technology industry in the United States.

The corporate campuses of the mid-20th century were built on greenfield sites. The best of them, like Eero Saarinen’s General Motors Technical Center in Warren, Michigan, or the John Deere Headquarters in Moline, Illinois, exuded the optimism of postwar America and its booming economy. These campuses presented a forward-looking (if somewhat sterile) view of work life and corporate innovation. New products and ideas would spring from an isolated company culture and then be disseminated to the world by truck and plane and through broadcast and print media. These campuses also signaled white flight, the accelerating decentralization of the American urban landscape, and the dominance of the automobile.

Apple Park does not critique these precedents – it accepts decentralization and the suburban condition – but it evolves the model. Silicon Valley is not a typical suburban region, of course. Norman Foster notes the region’s “homegrown affinities,” which make it fertile territory for technological innovation: Stanford University, an array of hardware, software, and internet companies located nearby, an educated and skilled workforce, a vibrant start-up culture, and access to capital. “The landscape has this wonderful California spirit,” Foster recalled. “There is a sense that anything can happen there.”

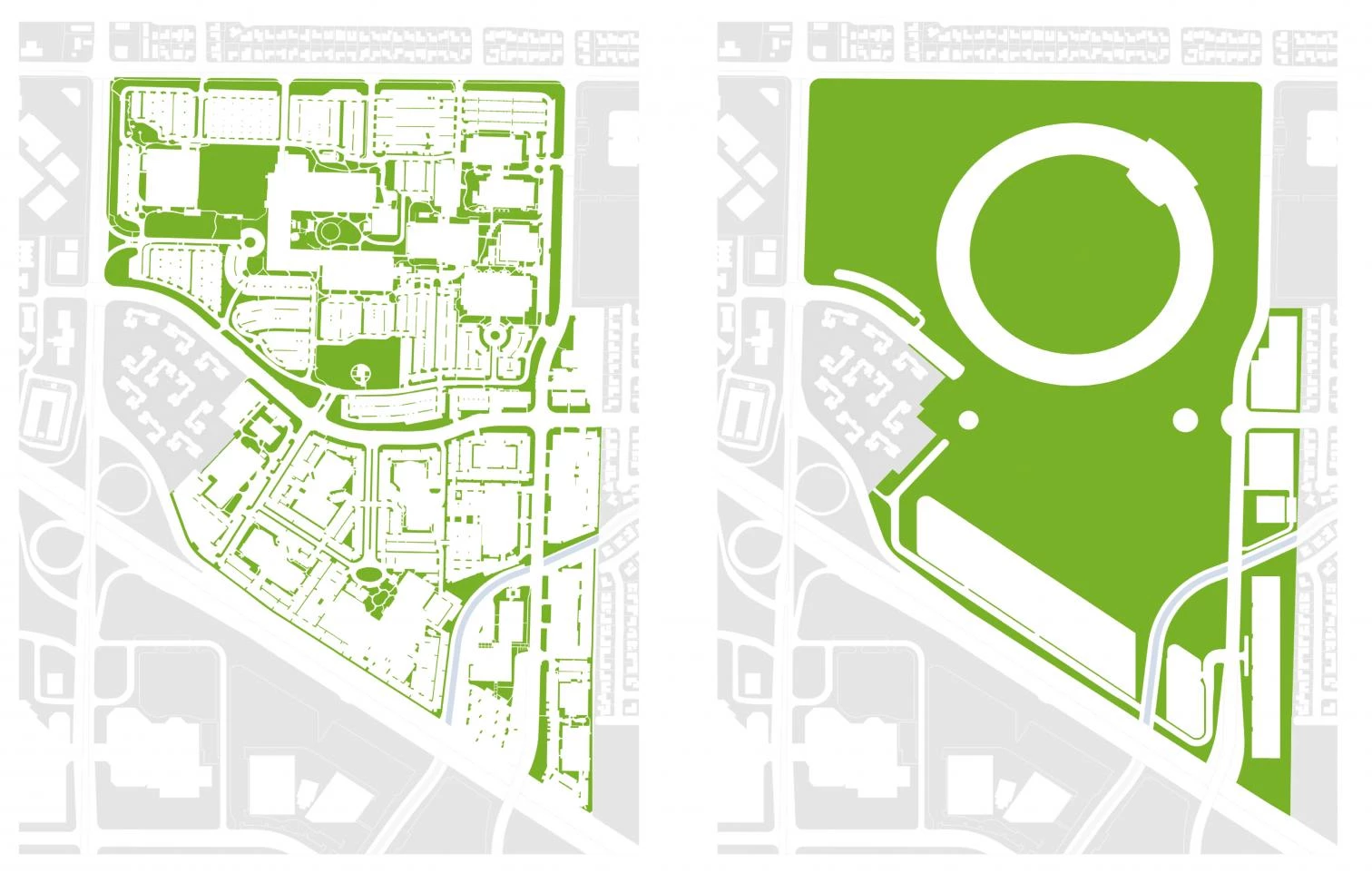

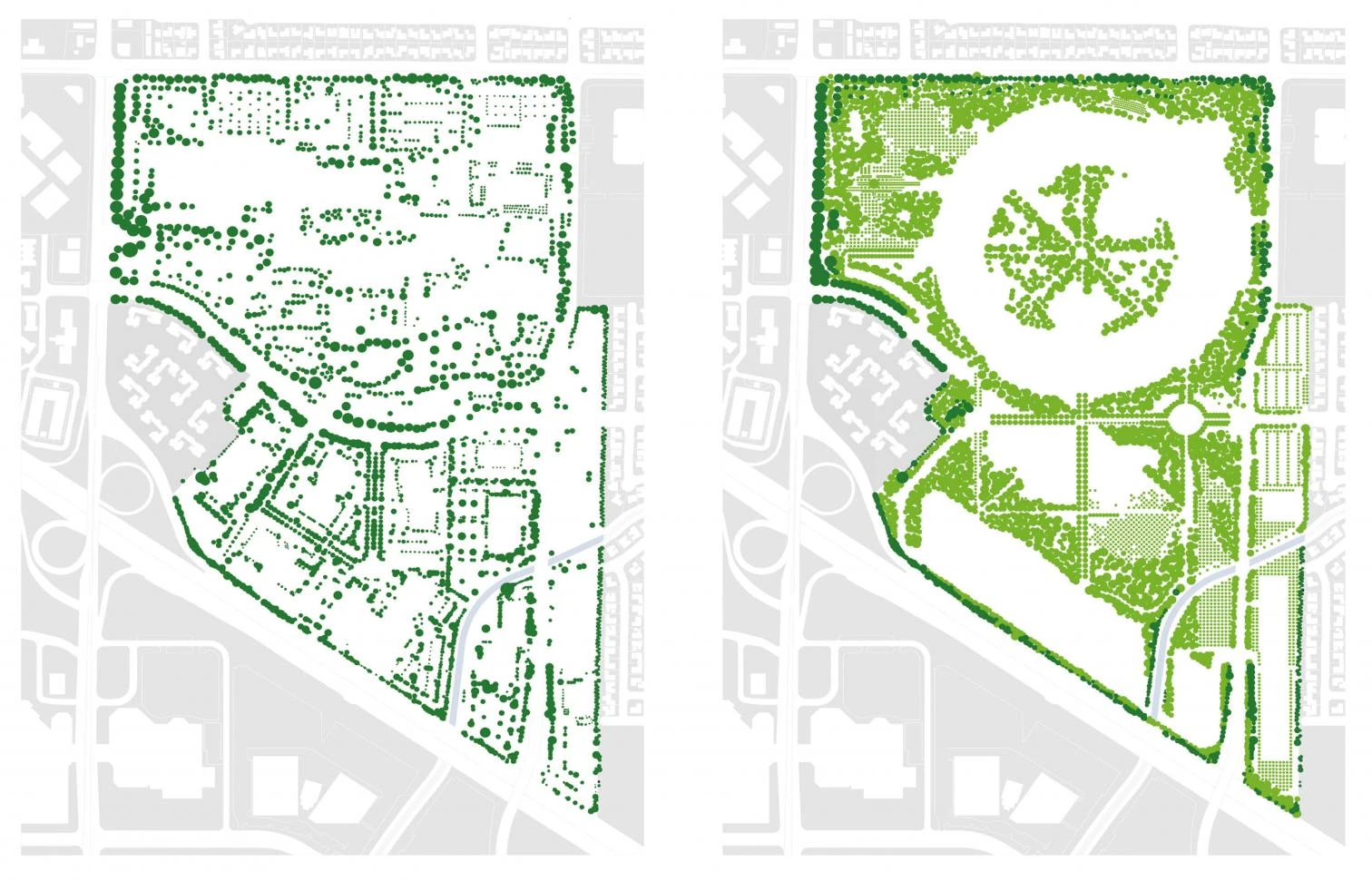

A Landscape in the Landscape

Built on the site of the former Hewlett Packard headquarters, Apple Park reintroduces an element of the natural into a formerly paved corner of Silicon Valley. Working with Philadelphia-based landscape architects OLIN, Foster + Partners has turned the 175-acre site, formerly covered in parking lots, into a tree-filled campus with winding paths and two-mile miles of running and walking trails for employees. Before his untimely death, Steve Jobs, Apple’s cofounder and CEO, personally selected many of the 9,000 drought-resistant trees; some are fruit orchards, which evoke the landscape of his California youth.

“I want to leave a signature campus that expresses the values of the company for generations,” Jobs told his biographer, Walter Isaacson. Isaacson writes that Jobs selected Foster + Partners for the project because Jobs considered them to be the finest architects in the world. Norman Foster describes a hands-on and highly personal working relationship between himself and Jobs. “Steve and I shared a vision for the project,” Foster said. “It was the coming together of two teams to ultimately become one.”

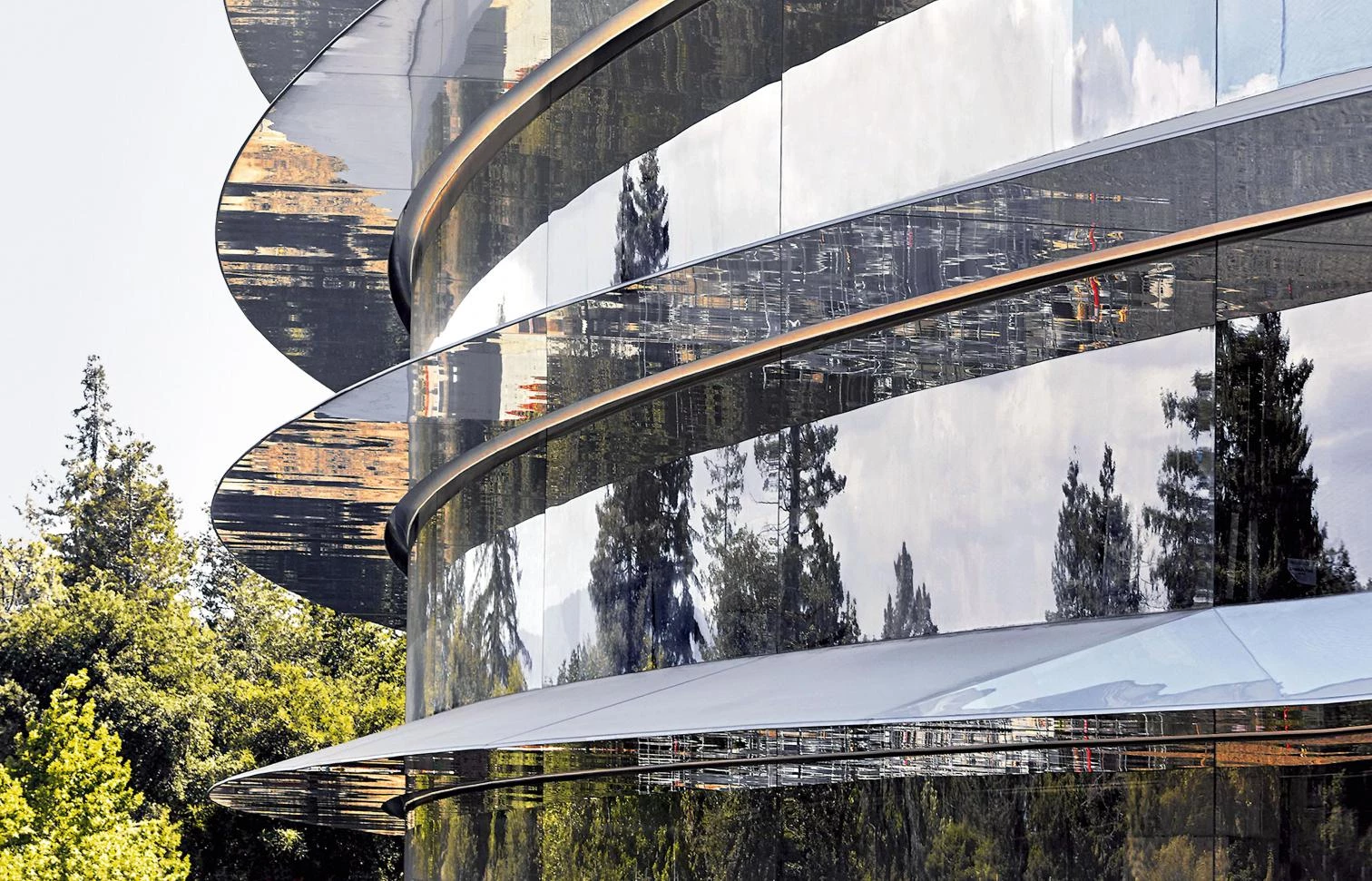

The attention to design, the quality of materials, and the innovative spirit that distinguish Apple's products is transferred to the Cupertino building, the smooth facade of which is fitted out with the world's largest curved glass.

Certainly, the rigor and elegance of the work of Foster + Partners is well-matched to the culture of Apple, as is the company’s interest in advancing research and material development. (The relationship has proven to be an enduring one; Foster + Partners is also now designing many of the company’s flagship stores all around the world.) Apple’s design and technology has transformed everyday objects, elevating electronics, personal devices, and information platforms to status symbols and objects of desire. They didn’t invent the smart phone, they just made the best one. The strongest Apple products (the iPhone and the Mac OS) are intuitive to use and feel like an extension of the body.

The building is conceived similarly, with the plan of relating to the physical and mental demands of the 12,000 employees, giving them access to natural light and air and sweeping views of the landscape. Workers sit in clusters by department in a wide variety of office types, emphasizing a democratic, non-hierarchical culture where information can be easily shared and collaboration is encouraged (Wired magazine, one of the only publications allowed inside the building, nevertheless reports that there are cordoned-off areas for top-secret research and product development, proving even the most democratic design intentions often collide with programmatic realities).

Circulation is pushed to the endless, smooth perimeter, underscoring the restive vistas of this manmade arcadia. Much like Apple worked with the glassmaker Corning to create the ultrathin screens for the iPhone, Foster + Partners has developed the world’s largest curved glass panels, which give the building its taut and seamless skin – the kind of research and innovation for which the firm is known. Glass shades extend from the building, diminishing solar heat gain and glare. During the region’s long stretches of temperate weather, the building will use natural ventilation for cooling, switching to air conditioning on only the hottest days. Building integrated photovoltaics, working in tandem with an on-site solar farm, allows the entire complex to generate more electricity than it consumes – a laudable accomplishment for a consumer-products company in an age of rapid climate change.

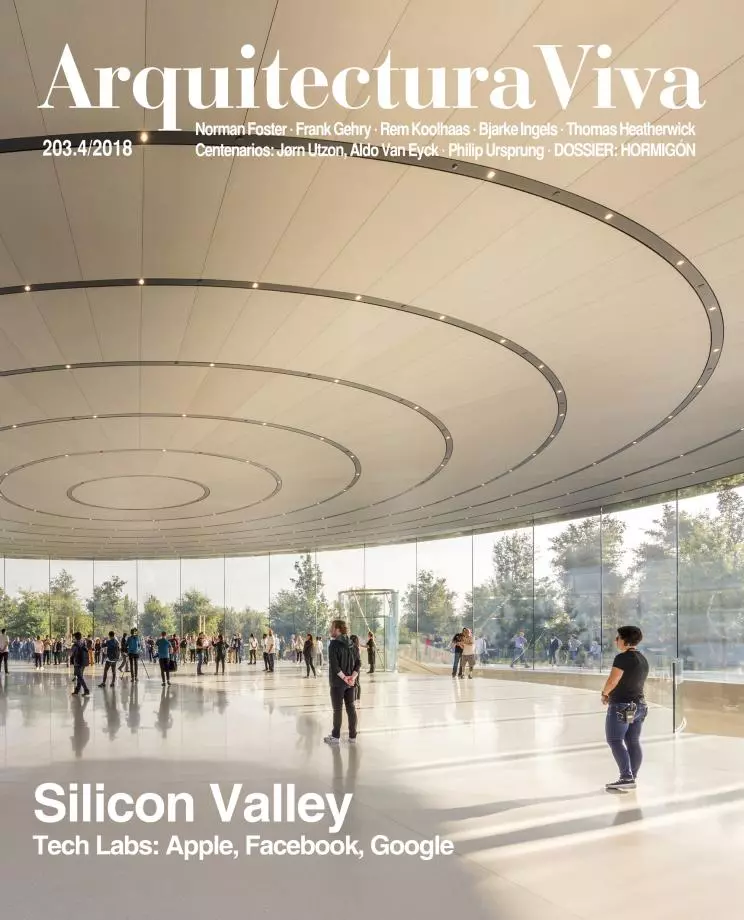

Also on site, the 1,000-seat Steve Jobs Theater perches atop a hill overlooking the main building, though the auditorium itself is below ground. Visitors enter the theater through a 165-foot diameter cylindrical glass entry pavilion capped by a saucer-shaped carbon fiber roof. Some of the company’s hotly anticipated – and widely broadcast product launches – will be held in the space, bringing the world, via video link, into the depths of Apple Park.

Within the complex rises the new Steve Jobs Theater, which one reaches through a glass cylinder 50 meters in diameter, crowned with a carbon-fiber roof that has the shape of a flying saucer.

For employees who never worked under Steve Jobs, Apple Park stands as a built manifestation of his vision, one that will serve the company for decades to come. “I think we have a shot at building the best office building in the world,” Jobs told Isaacson. He may have succeeded, but compelling questions remain. Was his notion of a ‘signature campus’ an expression of Apple’s future, or a nostalgic longing to return to the Valley of his youth? Will it inspire other technology companies to build and develop in more sustainable ways? Perhaps most importantly, is the destiny of corporate America and innovation located in a suburban Eden, or in the messy energy of its resurgent cities? It is up to the next generation to decide.

Deborah Berke, an American architect and academic, is dean of the Yale School of Architecture.

Obra Work

Nueva sede para Apple; Apple Park Campus in Cupertino

Arquitectos Architects

Foster + Partners

Fotos Photos

Mikael Jansson; DJI Phantom 4 Pro; iMore; Mark Mahaney; Nigel Young / Foster + Partners