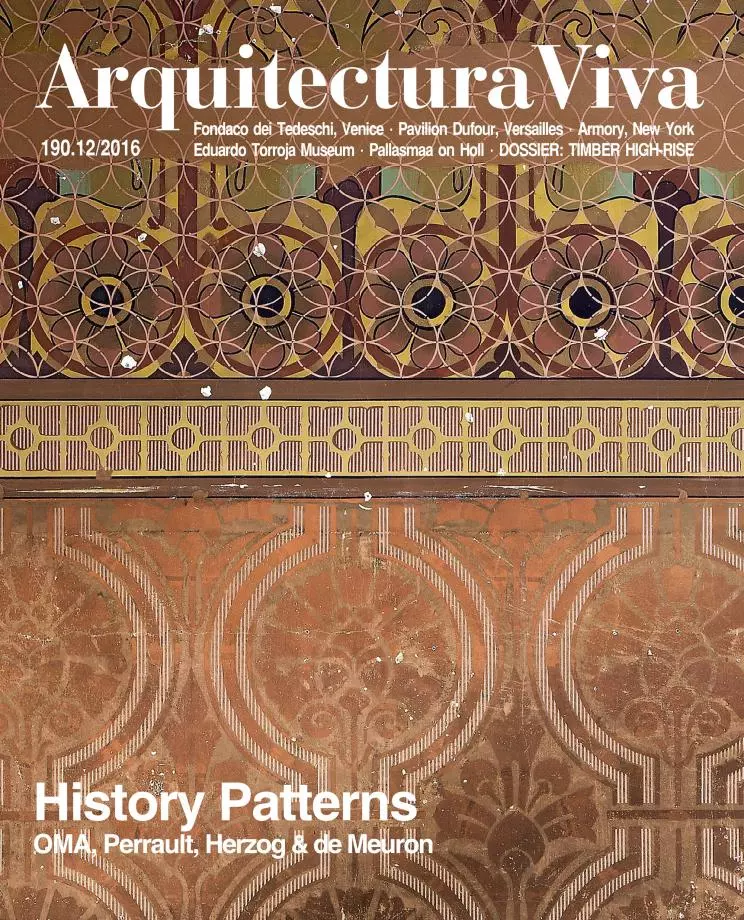

Refurbishment of the Pavilion Dufour at the Palace, Versailles

The Invisible Pyramid, by Michèle Champenois- Architect Dominique Perrault Architecture

- Type Refurbishment

- Material Aluminum Metal

- Date 2011 - 2016

- City Versalles

- Country France

- Photograph André Morin Gaëlle Lauriot-Prévost Vincent-Fillon Patrick-Tourneboeuf

Twenty years after the Bibliothèque Nationale de France was inaugurated by François Mitterrand in Paris, on the banks of the Seine, Dominique Perrault has at the Palace of Versailles completed work on the Pavilion Dufour, now fully transformed to accommodate a reception foyer, a restaurant, an auditorium, and new spaces created under the Cour des Princes. It has been three years of complex work around a brilliant solution that manifests itself externally only in the exit staircase that ends the visitor route, the ‘Perrault Stair.’

At once radical and “respectful towards heritage” (in the architect’s own words), the pavilion’s transformation introduces visitors to the splendor of the palace. The introduction is effected through a majestic modern space in a halo of golden light, decorated by the designer Gaëlle Lauriot-Prévost, a habitual collaborator of Perrault.

The architect has been successful in this first challenge with a great historical monument. He has managed to adjust problems from inside, and consolidate and restore the pavilion’s old wing, in collaboration with Frédéric Didier, chief architect for historical monuments in charge of Versailles. The result is a large reception space and a very clear-cut visitor route in a key enclave of the history of France which attracts 7.5 million visitors a year, three-fourths from abroad.

As regards the precedent at the Louvre, with Pei’s pyramid in the 1980s, one could say that Versailles has achieved what Perrault calls a “timeless piece.” Inserted in a historical site, it is an “invisible pyramid,” given that the only element visible on the outside is the glazed volume accompanying the Perrault Stair and which, through a prismatic refration effect, collimates natural light to distribute it through the basement.

In 1989, when Dominique Perrault won the international competition for the Bibliothèque Nationale de France, he was 36 years old. He had to deal with virgin land, an area open to conquest, creation, and invention. Since the library opened in 1996, a new neighborhood has grown around it, giving eastern Paris a real urban configuration. Where the library towers now stand, there was nothing. But in Versailles, with the royal enclave consisting of the park, the palace, the museums, and the Trianons, there was everything. Everything that – from the mid-17th century under Louis XIV to the early decades of the 19th under Louis- Philippe – has formed a coherent precinct devoted, as printed on the pediment of the Pavilion Dufour, “to all the glories of France.” The architect’s concern has been to understand the built place and restore the “substance of heritage.”

The architectural and landscaping coherence of the complex has strengthened with time, and the Republic has never stopped honoring the legacy of the monarchy, upholding Versailles as a national monument to respect and venerate as well as a venue for grand events of international diplomacy.

Grand receptions have been the vocation of Versailles since the Sun King. The very way it presents itself toward the city, with the palace’s horseshoe ground plan, is an invitation to enter and be led into the intimate space of the Cour de Marbre. This layout is enhanced by two symmetrical pavilions designed by Ange-Jacques Gabriel at the close of the 18th century. The north one was erected in 1771 and now bears the name of its architect, author, too, of the buildings that border the Place de la Concorde in Paris, while the south one was raised starting 1814 by Alexandre Dufour, following plans left by Gabriel.

Immersed in the heart of the monumental chaos that lies behind the classical facades and symmetrical layout, Perrault became an explorer of the enclave, determined to understand the building, dig into its history, get to the bottom of the foundations both literally and figuratively, create new underground spaces, and enlarge existing buildings. The architect has treated the commission as an opportunity and a step forward in the development of what he calls ‘groundspaces,’ dug out spaces. The term coined by Perrault also resembles the title of a recent book (Groundscapes-Autres topographies, Éditions HYX, 2016) that discusses the design strategy used in Seoul Women’s University, the Court of Justice of the European Union in Luxemboug, or the unexecuted project for the Mariinsky Theater in St. Petersburg.

The spring 2016 opening of the reception hall, the June inauguration of the Pavilion Dufour by François Hollande, President of the Republic, and then its final completion in September, with the restaurant to be run by the multi-awarded chef Alain Ducasse, illustrate the importance of the project, which in creating new facilities (reception, a restaurant, and an auditorium) has restored the classical architecture of the building and retained the symmetrical configuration of the monument, while ensuring fluid access and movement for the millions of visitors arriving at Versailles, many of them for the first time.

From Inside Out

The brief of the 2011 competition allowed constructing a new facade, but Perrault was the only contestant who opted not to, instead proposing what would make him the winner: the virtual invisibility of a major intervention on the Versailles complex, enhancing its symmetries and adapting to the crowds of tourists without interfering with the monument’s fundamental aspects.

Perrault redistributed the interiors, unraveling the tangle of passageways, demolishing the partitions added in the course of time (especially the thick structure of reinforced concrete that went up in the 1930s), and also eliminating divisions that had been made in the attic in the 1990s, when renovation work was carried out to make room for offices. For his part, Frédéric Didier, chief architect for historical monuments, issued directives for restoring the facades and roofs and also the vaulted rooms underneath the Cour des Princes, as well as for recovering the stone foyer along the pavilion’s facade. Together the two architects have preserved the exedras of an old hall, and even a hidden staircase that had been found, adding to the discovery of the foundations of an old wall – a find which brought out the vaulted rooms in all their splendor – and of some old cisterns that now house the bookstore and souvenir shop located at the point where the visitor route ends.

On the outside, the pavilion is very discreet. More liberties have been taken indoors, where Gaëlle Lariot-Prévost has masterfully designed subtle fabrics of wire mesh, besides the diversity of light fixtures adorning the restaurant rooms, the metal-clad stairs, and the elements providing visual and acoustic comfort in the attic auditorium. Together these features result in a coherent and inventive decoration that enables contemporary art, as exemplified here in the work of Claude Rutault, to have its own place in the history of Versailles.

The south wing has been freed up completely by transferring the offices of the palace conservators to a general administrative area situated in what is called ‘Le Grand Commun,’ on a street adjacent to the palace. The move was the fruit of an ambitious masterplan drawn up in 2003, which subsequent administrators – beginning with former culture minister Jean-Jacques Aillagon, who was followed by Catherine Pégard, appointed head of the organism in charge of the palace, museum, and national estate of Versailles – have implemented.

The pavilion is conceived as a point for welcoming people, a ‘regal’ reception place on a par with the symbols of French history and the prestige of the founding monarch. At the entrance, visitors are bathed in a golden light. With her mastery of the scenography, Gaëlle Lauriot-Prévost’s rigorous design is fearless in engaging in dialogue with the building’s baroque imagery. The pleats, the drapes, the suns (of the Sun King), and their reflections can be translated to the contemporary language without loss of force. The halo of golden light becomes a metaphor.

The light fixtures are fixed to horizontal posts, under a canopy of wire mesh whose irregular drapery dresses the pavilion’s high ceilings in waves. Around the projectors, a light feature tangled in petals of golden anodized aluminum multiplies the powerful luminous fountain through sparkles, and projects images through reflections. The unity of the ceiling (from some points the large waves of the drapery seem to calm down) is achieved through the choice of material: a wire mesh dropped over the rear wall like a stage curtain. As for the reception counters, they take on a neutral presence through their shape and their color (black). The whole floor has been re-clad with metal, through a ‘Versailles-type’ parquet that follows the classical model with diamond patterns and is composed of heat-laminated plates of metal the color of anthracite, which gives them a bluish iridescence.

On the first floor is the restaurant Ore, entrusted to Alain Ducasse, whose decoration is comfortable and sedate: the wooden plinths take on protagonism, and the ceiling is adorned with suns formed by luminous tubes fastened to one or more circular supports. The bar is lit with similar tubes, which drop like stalactites towards the counter. A wire mesh collar, golden and pleated, serves as a screen and gives the light a magical twinkle.

On the top floor, an auditorium seating 150 occupies the space under the roof. A structure of horizontal wooden strips forms an acoustic shell independent of the stone masonry. The intimate atmosphere of this stranded ship is accentuated by its simple and relaxing appearance.

On the stairs we again find luminous tubes, this time in a horizontal position and set on cables with tensors that float between the flights of steps. Whatever route they take, all visitors to the pavilion end up in the vaulted spaces of the old kitchens, where the museum store is delicately placed, looking larger than it is thanks to the lighting.

As they approach the exit, visitors to Versailles are once again bathed, though only for an instant, by that same copper-like light they saw when they first entered the building, which comes from a glazed volume whose walls of anodized aluminum, golden and matte, create a very gentle light by means of reflection. Again there is a wall of light… but also the symbolic expression of a reflexive approach which has ultimately made possible a gentle reconciliation between contemporary architecture and historical heritage.

Obra Work

Rehabilitación del Pabellón Dufour en Versalles (Francia) Refurbishment of the Pavilion Dufour at the Palace of Versailles (France).

Cliente Client

Opérateur du patrimoine et des Projets Immobiliers de la Culture / Etablissement Public du Château, du musée et du domaine national de Versailles.

Arquitectos Architects

Dominique Perrault Architecte.

Consultores Consultants

Gaëlle Lauriot- Prévost Design (dirección artística artistic design); Jean-Paul Lamoureux (acústica e iluminación acoustics and lighting).

Fotos Photos

André Morin (pp. 28, 29, 30, 32, 33 abajo bottom, 37); Gaëlle Lauriot- Prévost (p.33 arriba top); Vincent Fillon (pp. 34, 35); Patrick-Tourneboeuf (p. 36).