Venice, Lions and Chimeras

The Venice Biennale shows the changing forms of the latest currents in the 9th edition of its international architecture exhibition, with the title

The lion of St. Mark is a chimera. It appears that the bronze figure representing Venice’s patron saint is a 4th-century chimera that came from the eastern Mediterranean. The city, then, has in its possession not only the Evangelist’s body, brought in from Alexandria by 9th-century crusades, but also his sculptural symbol. It is an image that different mostras of the by now centenary biennale have handed out as an artistic or cinematographic trophy. And few events have deserved to be feted with Golden Lions as much as the latest Mostra di Architettura, an exhibition profusely supplied with projects of monstrous beauty and imaginary nature. Baudelerian in its exaltation of convulsive beauty, surreal in its penchant for exquisite corpses, and postmodern in its celebration of ruptures and torsions, the Biennale put together by Kurt Forster under the motto Metamorph explores a territory rich in fractal topographies and digital warpings, a terrain as molded by biomorphic expressionisms as it is veiled by shadows or reflections, and surely closer to Kafka than to Ovid in its register of organic mutations and formal traumas. As much for architects who discovered Venice by way of Ruskin’s Gothic rigorism as for those who came through Tafuri’s critical Renaissance prism, this Biennale promises to be tiresome and pedagogical.

St. Mark’s winged lion, symbol of Venice and model for the awards of the biennale, represents an ancient chimera.

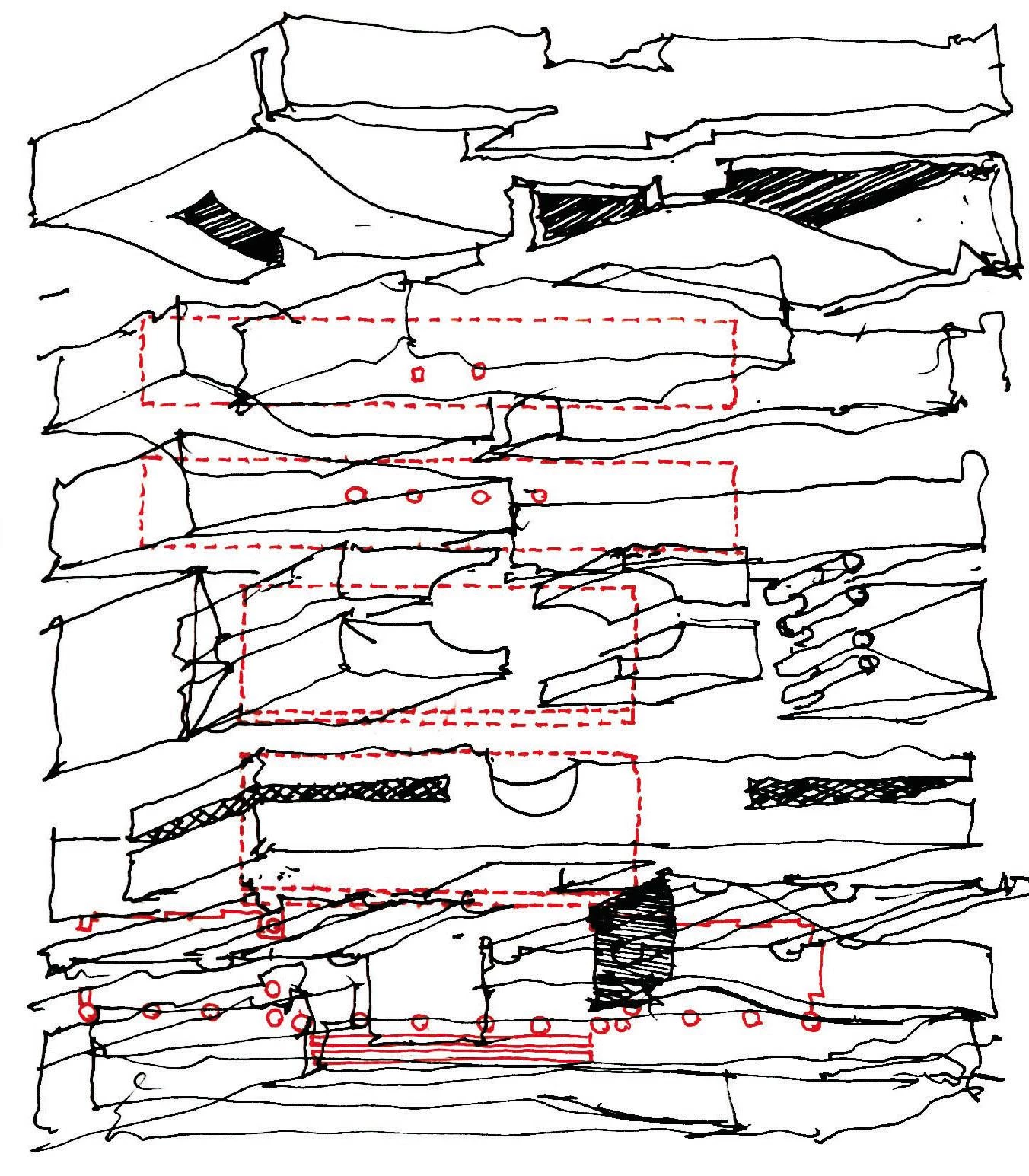

Peter Eisenman received the Golden Lion for his entire career, culminating an ‘Italian’ year highlighted by the publication of his book on Terragni, the honoris causa doctorate in Rome’s La Sapienza, and the installation of the Castelvecchio of Verona, a dialogue with Scarpa that is still visitable, as is his intelligent scenography in the Biennale itself, where the formal journey that leads from Palladio and Piranesi to the work of the New Yorker, with a stop at the author of the Casa del Fascio, is materialized in a syntactic promenade through an architectural chimera built with slices of buildings juxtaposed like anatomical fragments of the mythical animal. The Golden Lion for works presented in the official section fell upon two projects of the Japanese studio SANAA (Kazuyo Sejima and Ryue Nishizawa), the just finished 21st Century Museum of Contemporary Art in Kanazawa, an unorthodox complex of exquisite prismal halls enclosed in a glass circle that subjects the program’s random demands to the luminous rigor of geometry, and the as yet uncertain enlargement of Valencia’s IVAM: two museums whose light serenity contrasts with the storm that shakes the landscapes of the Biennale.

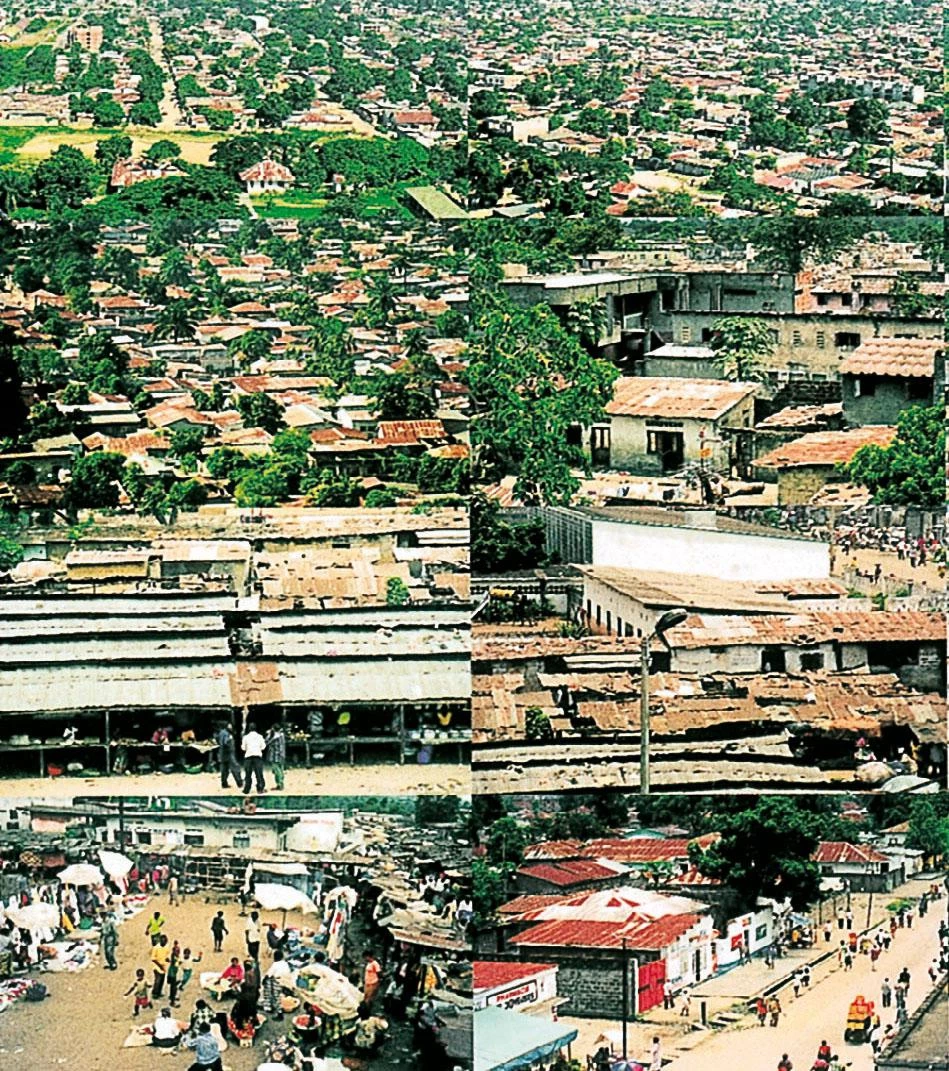

Finally, the Golden Lion for Best National Pavilion went to Belgium’s, a pòvera installation of blackboards and screens on Kinshasa – selected in the pre-Biennale competition organized by the young Flemish Institute of Architecture – that from the angle of post-colonial anthropology asks essential questions about the immaterial nature of urbanity in a chaotic, dynamic country still burdened by the memory of the Congo of Leopold, which brought western arrogance to the heart of darkness.

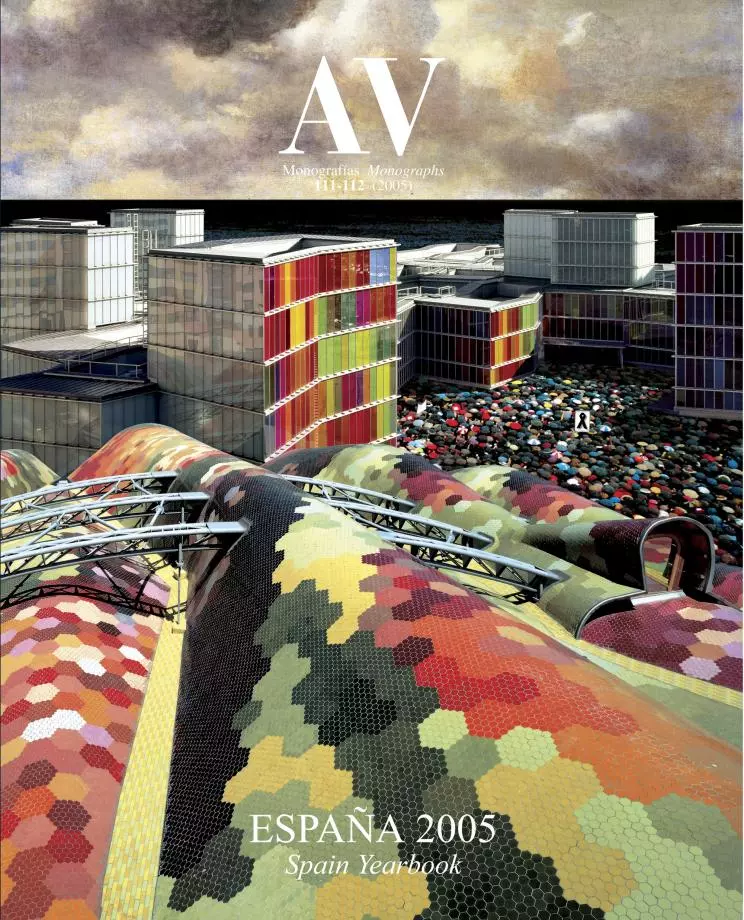

The Japanese office of Sejima & Nishizawa received the Golden Lion to the works in the main show for two museums of contemporary art, the one built in Kanazawa and that designed for the Spanish IVAM.

Other sections distinguished projects of young teams like those of Denmark’s Plot (Julien de Smedt and Bjarke Ingels) in Stavanger and London’s FOA (Alejandro Zaera and Farshid Moussavi) in Basel, two provocative proposals that join landscape and construction to imagine a topographical urbanity; works that use tormented geometries to test spatial innovations, such as the Japanese Shuhei Endo’s sheet metal loops that blur interior and exterior, or to express political ruptures, such as the fissures used by the Austrian veteran Günther Domenig to fracture the intimidating regularity of Nazi architecture in the Documentation Center of Nuremberg; and major projects linked to events, such as Torres & Martínez Lapeña’s esplanade, the central piece of the Barcelona Forum, or the Swimming Center that the Sydney office of PTW is building in the heart of Olympic Beijing amid much difficulty and controversy that the prize may help overcome (tribulations, incidentally, that it shares with the two grand ‘missings’ in this year’s Venetian event, namely OMA/Koolhaas and Herzog & de Meuron, both with colossal projects for Beijing 2008 now under revision). Finally, the award for best installation went to that put together by the photographer Armin Linke with the architect Piero Zanini, and for best photograph among those assembled by Nanni Baltzer the jury chose one of planet Mars taken by the NASA probe, the day after the capsule Genesis crashed into the Utah desert!

Peter Eisenman, who designed a syntactic installation for the Venetian mostra, was awarded the Golden Lion for an oeuvre that has significantly inspired many of the projects shown in the Corderie.

The Belgian, that showed the urbanism of Kinshasa, was judged the best national pavilion, in competition with the critical proposals of those of Germany, Japan or Great Britain.

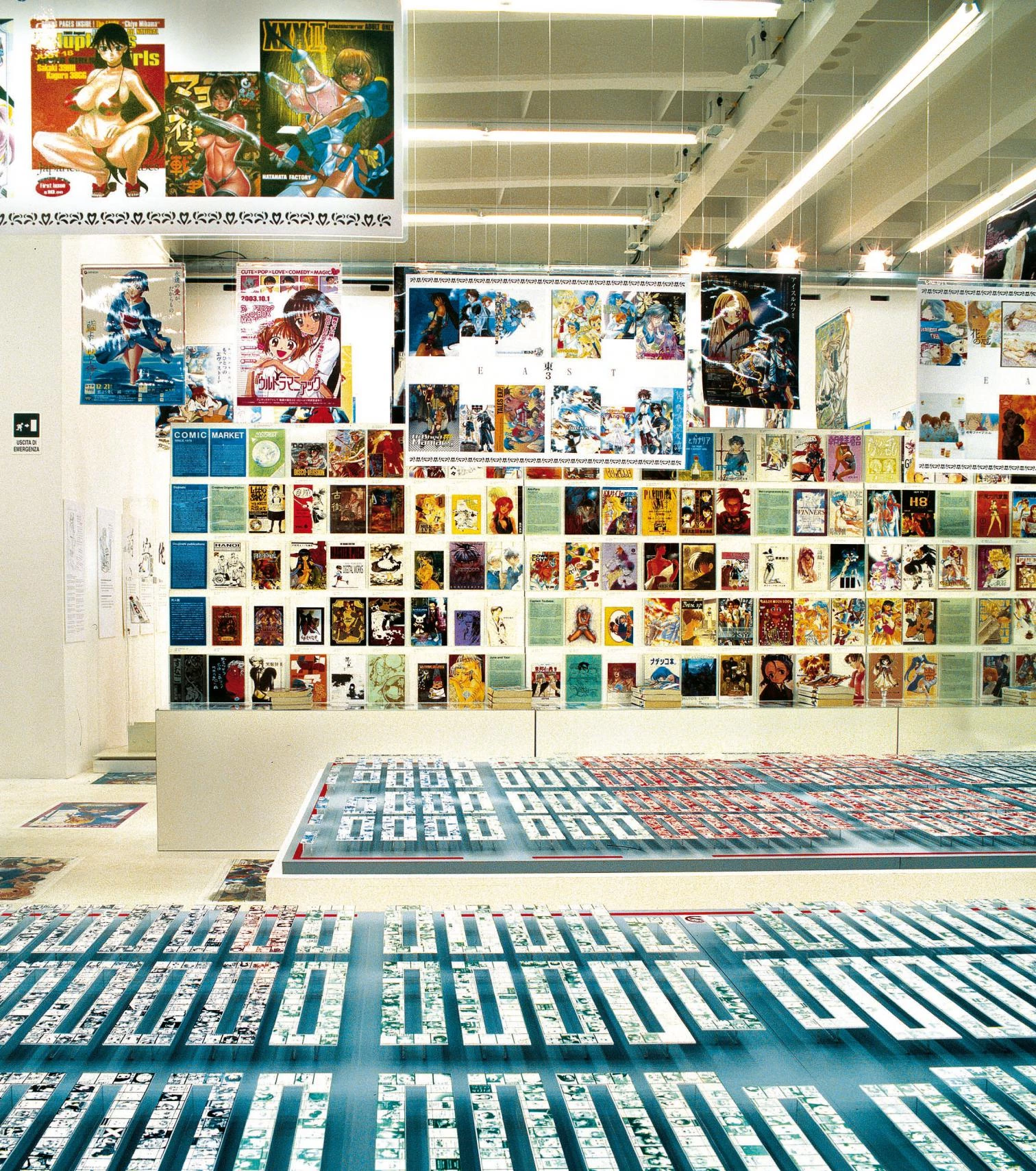

But beyond the random details of awards, visitors to the Venetian macro-exhibition – which unfolds on warped plinths designed by Asymptote in the Corderie of the Arsenal, in the labyrinthian packet of the Italian pavilion, or in the dispersed flotilla of national pavilions in the Giardini – will have the chance to verify both the centrifugal confusion of contemporary architecture and its determination to carve itself a niche in the media scene. From the disturbing spectacularity of the Japanese pavilion, which documents the half-puerile, half-pedophile culture of the so-called otaku, solitary youngsters obsessed with computer games and manga, to the insistent reinventing of the Danes, who have imported a luxury curator, the Canadian graphic designer Bruce Mau, to emulate Madonna, passing through the marketing skill of the British Pavilion with its canonization of personalities, or the critical intelligence of the German, which shows signature architecture gobbled up by the spread of junk urbanism, the journey through this accumulation of attention-seeking objects is bound to provoke a certain melancholy sense of saturation. Though it has become fashionable among movie stars like Brad Pitt, architecture cannot compete with Hollywood, and those who went (on the very day of the Golden Lion awards, and fifteen years after Pink Floyd’s concert before Sansovino’s loggetta) to the showing of Spielberg’s Shark Tale on the colossal stage set up on St. Mark’s Square will understand, with no need of explanations, that the spectacle of music or movies is not comparable to the more modest and persistent presence of the building in the city. Bellerophon managed to kill the Chimera with the help of Pegasus, but architects will need more than a winged horse to confront the monsters that the dream of reason engenders. Beside St. Mark’s winged lion, the Hellenistic figure of a warrior on a crocodile represents Venice’s original patron, St. Theodosius, in his struggle with the dragon. This image of the protector of Byzantine armies could perhaps serve as an alternative emblem of the necessary confrontation between architects and the chimeras of their imagination.