The Friendly Islam

The Aga Kahn Awards, which distinguish works for Muslim communities, have selected projects of very different scales, from the skyscraper to the shelter.

Architecture’s most generous prize is also the warmest. Including a US$500,000 endowment and handed out every three years, the Aga Khan Award is not bestowed on the authors of projects, but on the projects themselves, thereby placing the attention on architects, developers, and clients alike. Focusing on works carried out for Muslim communities, geographically it prioritizes a warm belt where poverty abounds, so the works selected tend to pay attention to climate issues and appropriate technology. And concerned about architecture’s ethical and cultural dimensions, its winners have transcended the strict limits of building to include anything from the restoration of monuments and urban renewal to emergency housing. Plural, regionalist, and responsible, the award given by the imam of Ishmaelite Muslims, hereditary spiritual leader of some 35 million believers spread throughout the world, is exemplary in its criteria, rigorous in its selection process, and commendable in the composition of its juries, which have been graced by the likes of Tange, Stirling, Venturi, Gehry, Eisenman, Siza, Zaha Hadid, or, in the last edition, the Catalan Elías Torres.

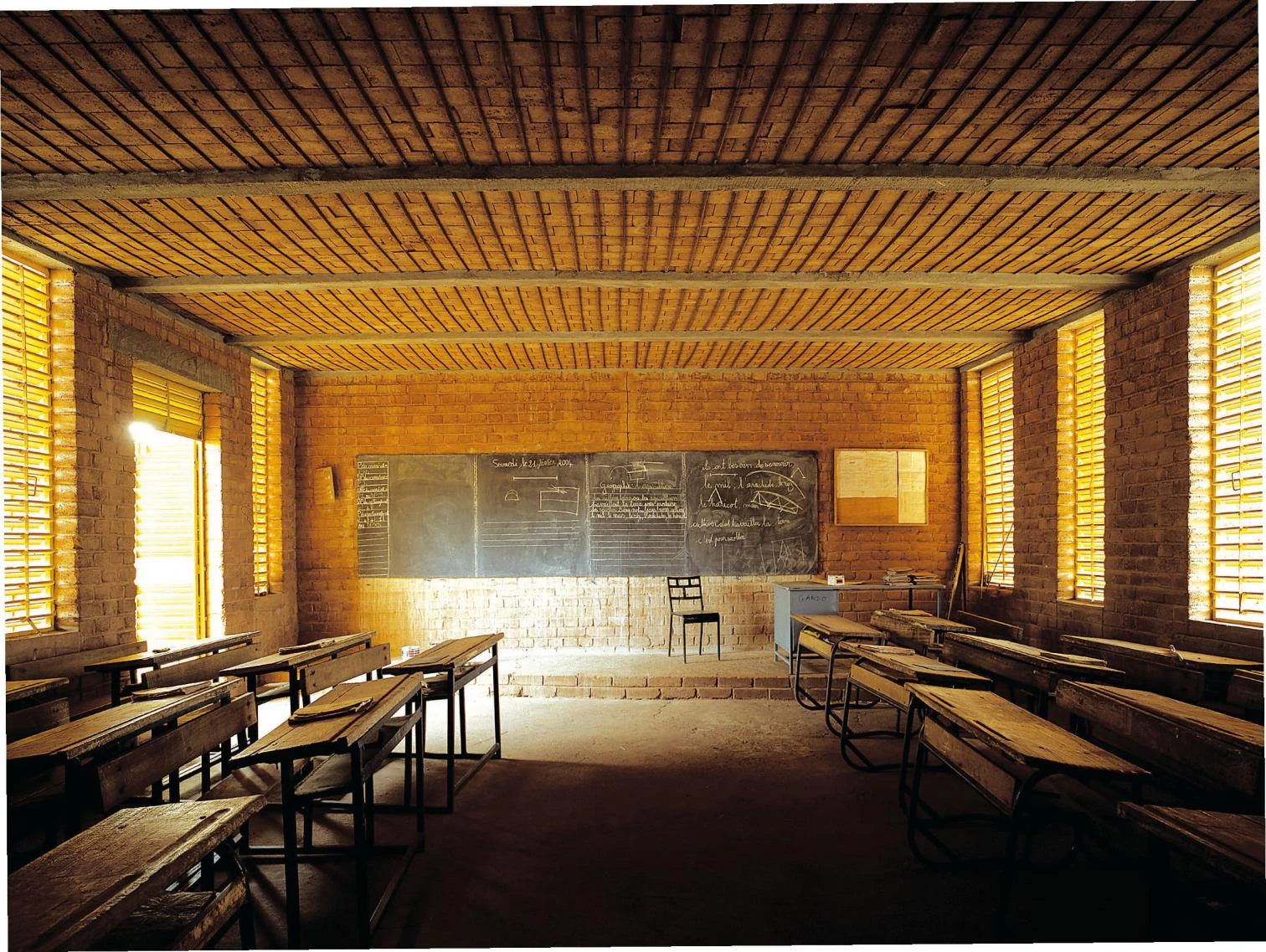

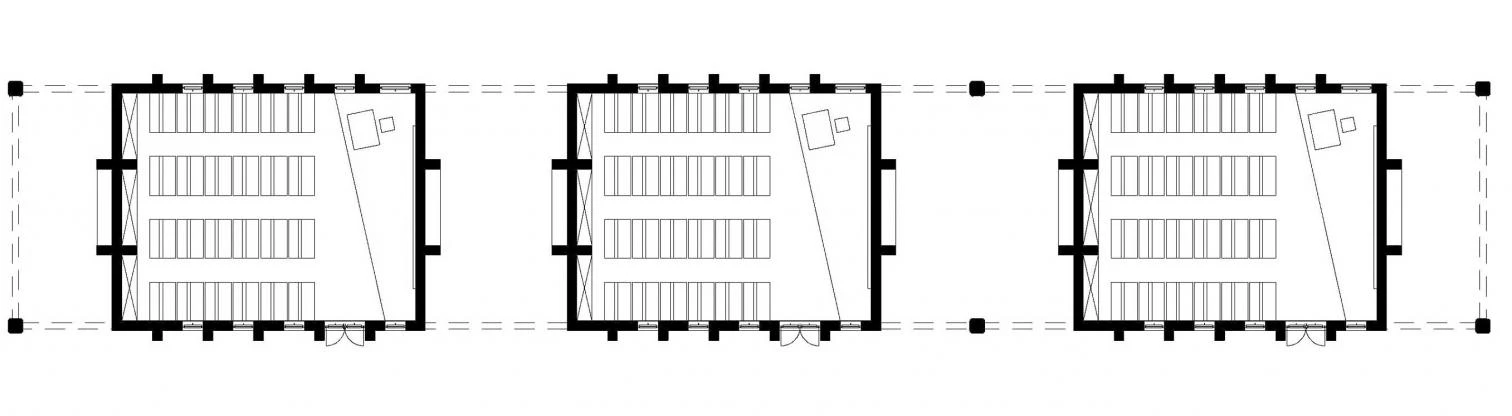

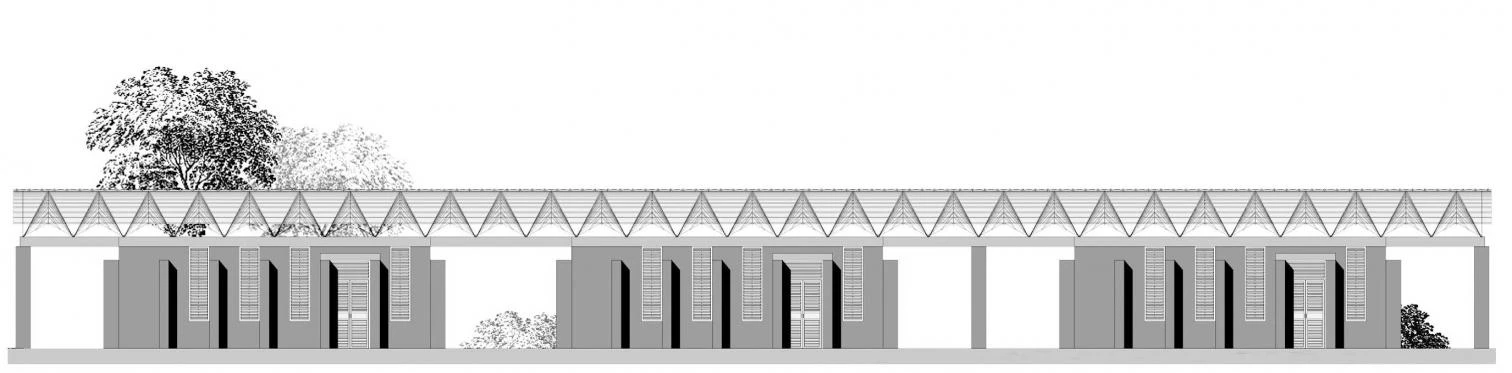

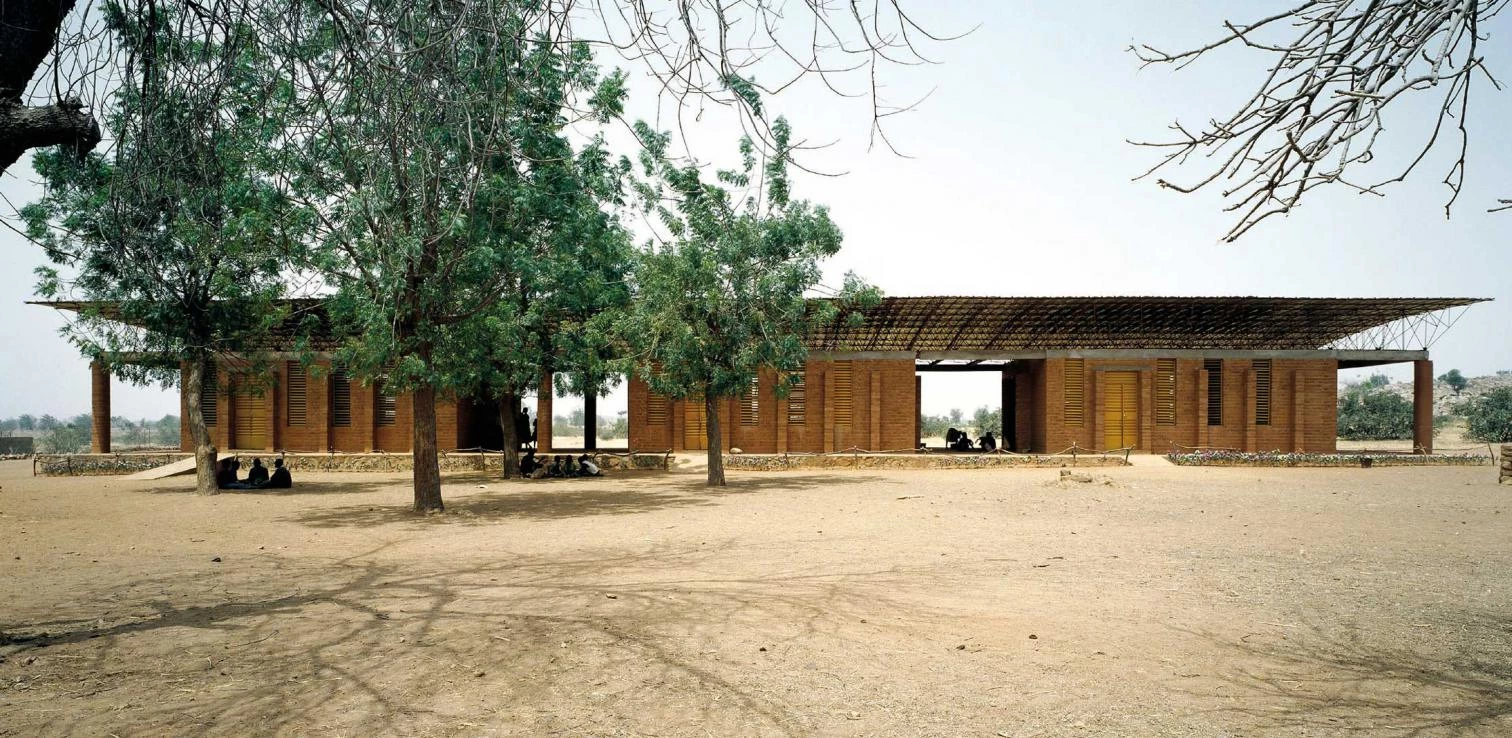

The primary school of Gando, in Burkina Faso, has three adobe-built classrooms sheltered by a corrugated sheet roof, held by a spaceframe, which provides shade to the perimeter porch and the intermediate voids.

It seems strange that a religious leader should be behind all this. Picture the Pope or the Dalai Lama spearheading an architectural prize. But this Geneva-born, Harvard-educated Shiite Muslim, a descendant of Muhammad through his daughter Fatima and symbolic heir of the scientific and intellectual achievements of the Fatimid dynasty, comes from a family whose most recent generations have been linked to international cooperation, first in the context of the League of Nations, which his grandfather presided, then within the United Nations, where his uncle, brother, and children have held important posts. Such a tradition of service underlies the Aga Khan network of institutions, which works for the improvement of living conditions in the planet’s least prosperous zones, and in fields ranging from architecture, education, and health to industrial or tourist promotion, rural development, and financing through microloans. Only in this context can one understand the uniqueness of an award that spontaneously arouses admiration and good feelings, but which in its ninth edition has rather blurred its lines by transferring emphasis, in the wake of a total overhaul of its executive committee and jury, from social and ecological responsibility to technical and symbolic experimentation.

Among the seven projects celebrated on November 27, in the course of a ceremony held in New Delhi and presided by India’s Prime Minister and the Aga Khan himself, are the Petronas Towers, the skyscrapers that the Argentinian-born César Pelli’s New Haven office built in Kuala Lumpur, from 1993 to 1999, as an architectural icon of the oil-triggered economic boom of Mahatmir Mohamed’s Malaysia: two giants whose world record for height and elegant evocation of Islamic tradition may have given them a picturesque popularity, reinforced through movies like the one that has Sean Connery and Catherine Zeta-Jones doing impossible acrobatics on its vertiginous peaks, but which indeed speak more of the representation of power than of social sensibility. A circumstance that is less prominent in the other great work of this year’s Aga Khan Awards, the Alexandria library, a monumental inclined disk completed two years ago by the Norwegian studio Snøhetta, winner of the 1989 competition organized by the Egyptian government and the International Union of Architects: a formidable cultural symbol and an urban milestone which launched the career of the young emerging Scandinavian office, elected recently to design one of the emblematic buildings of New York’s Ground Zero.

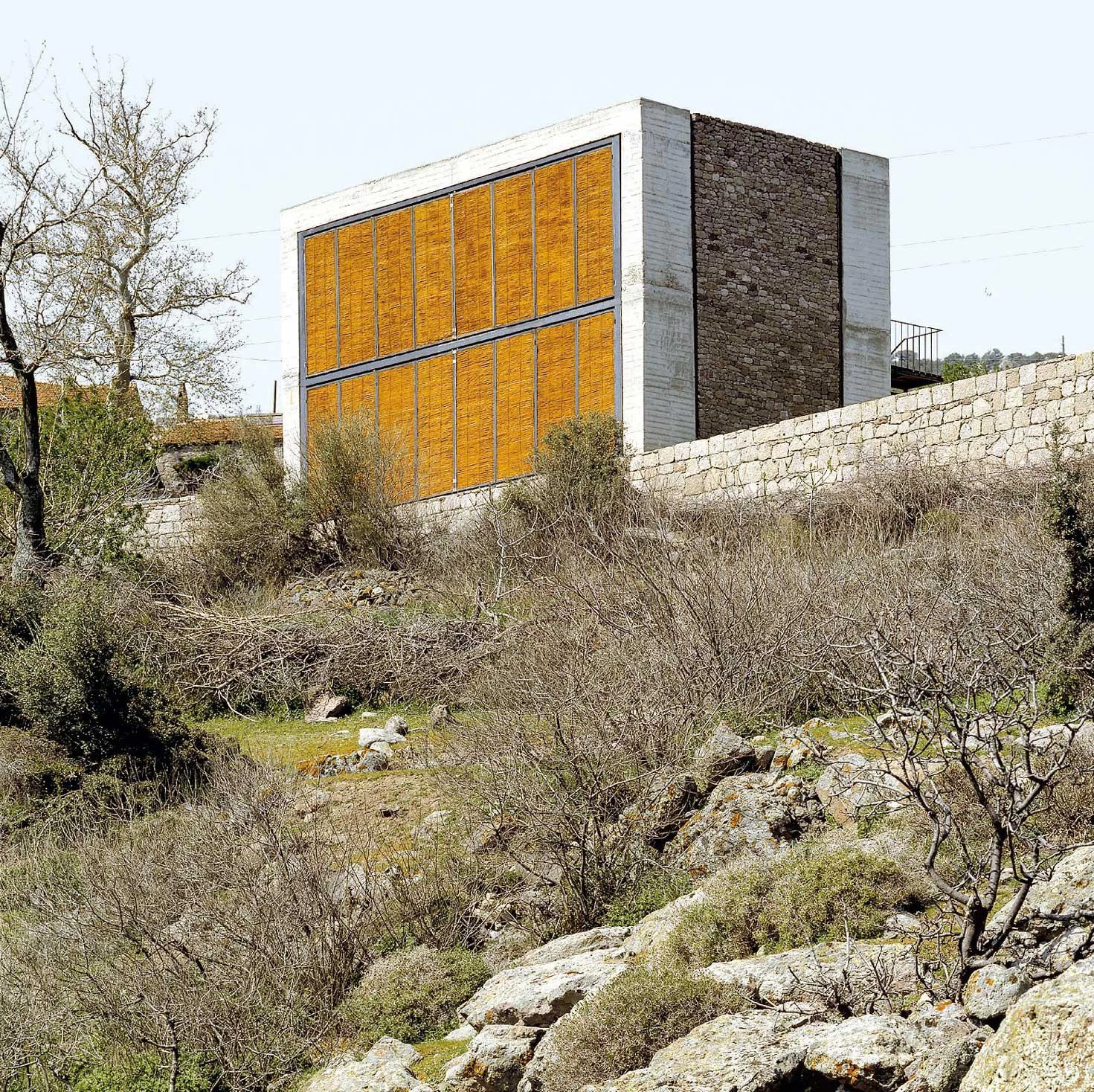

The B2 house, a summer residence on the Turkish Aegean coast, uses vernacular materials and simple techniques to shape a lookout effortlessly blended into the landscape that closes hermetically when not inhabited.

Three of the remaining projects belong to the alternative line of previous Aga Khan Awards celebrating excellence achieved with modest means. The primary school of Gando, in Burkina Faso, three simple adobe classrooms with porches in between and a light roof of corrugated metal overhead, was built by the village’s own inhabitants under the supervision of the son of the tribal chief, Diébédo Francis Kéré, who while studying architecture in Berlin obtained philanthropic funding with which to raise a structure that is exemplary in its social commitment, adaptation to climate, and formal purity. Similar in its combination of local techniques and geometric rigor is the B2 house on the Aegean coast, designed by Han Tümertekin as a weekend refuge for two Istanbul-based brothers, with humble materials shaping a minimalist lookout of singular dignity and solemn simplicity. As for the prototype of a shelter, developed in California by the Iranian architect Nader Khalili and used in various United Nations programs, the sandbags are placed in circles to form domes and the structure is reinforced with barbed wire, the usual materials of armed conflict thus put at the service of humanitarian emergency.

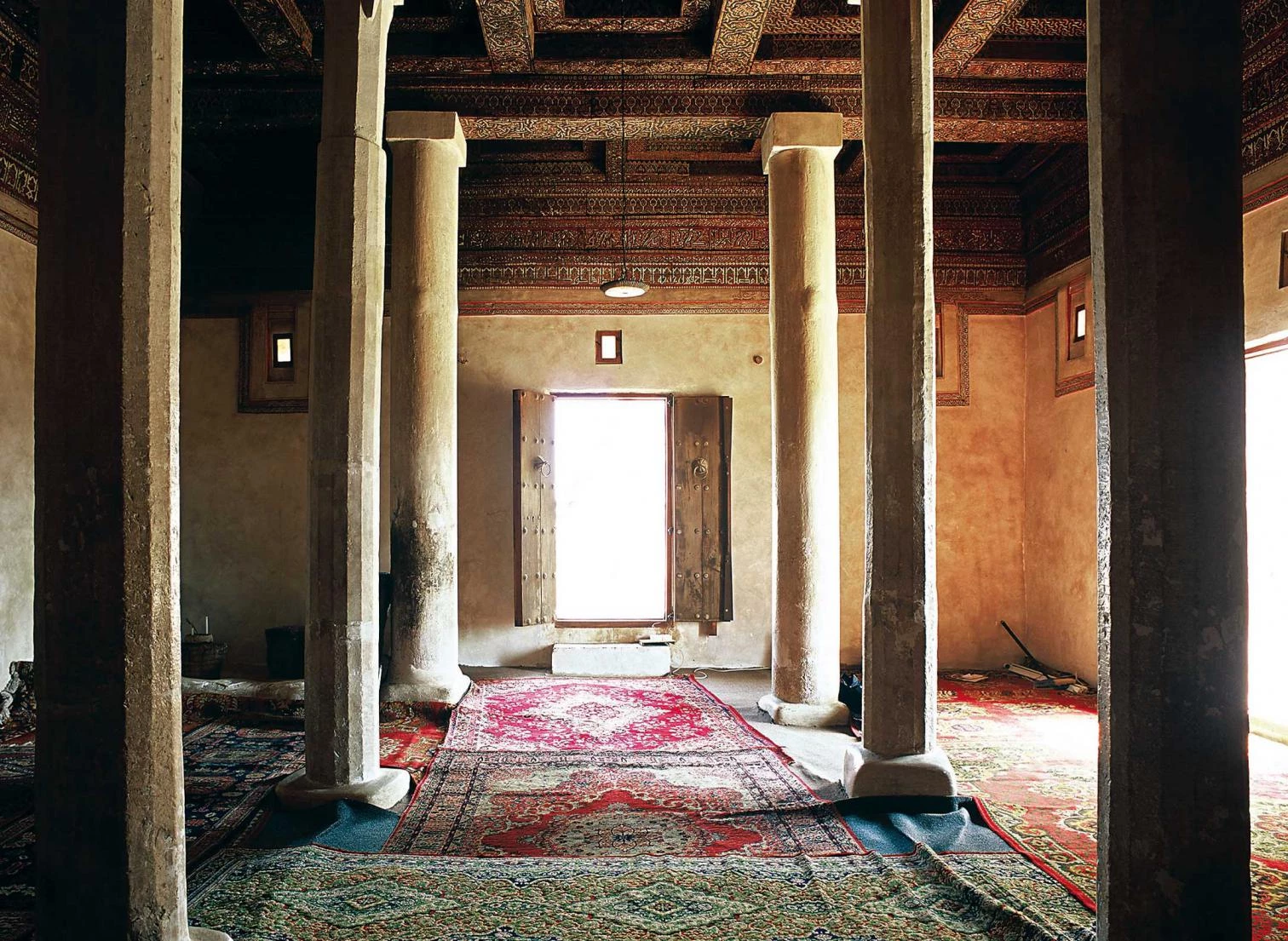

Finally, and also in continuity with previous awards, this year’s edition includes two interventions on heritage. The restoration of the mosque of Al-Abbas, a delicate, meticulously decorated cube built in Yemen in the 12th century, was carried out with utmost rigor by the French Marylène Barret in the course of ten years of precarious political stability in the country. And the program for regenerating the old city of Jerusalem, drawn up by a Swiss association that tries to ensure equanimity in an environment torn by hatred and violence, has undertaken over 160 rehabilitation projects to improve the living conditions of the Palestine population and maintain the cultural value and physical beauty of an urban entity of exceptional importance for three different religions, placed in a territory laden, as has often been said, with too much history for its limited geography. If we remember that the leader of the 19 suicide terrorists of 9-11 was an architect, Mohamed Atta, a self-declared enemy of cosmopolitan modernity who was writing a doctoral thesis, in a Hamburg university, on the urban heritage of the Arab world, we can understand up to what point the Aga Khan Awards pluck the nerve fibers of a Western world that insists on looking at the Muslim as ‘the other’, but also those of an Islamic world divided by abysses as extreme as those that separate skyscrapers of oil from igloos of sand.

The restoration in Yemen of the Al Abbas mosque or the rehabilitation of the old city in a Jerusalem torn by conflict contrast with the dome-shaped prototype of emergency shelter made of sandbags reinforced by barbed wire.