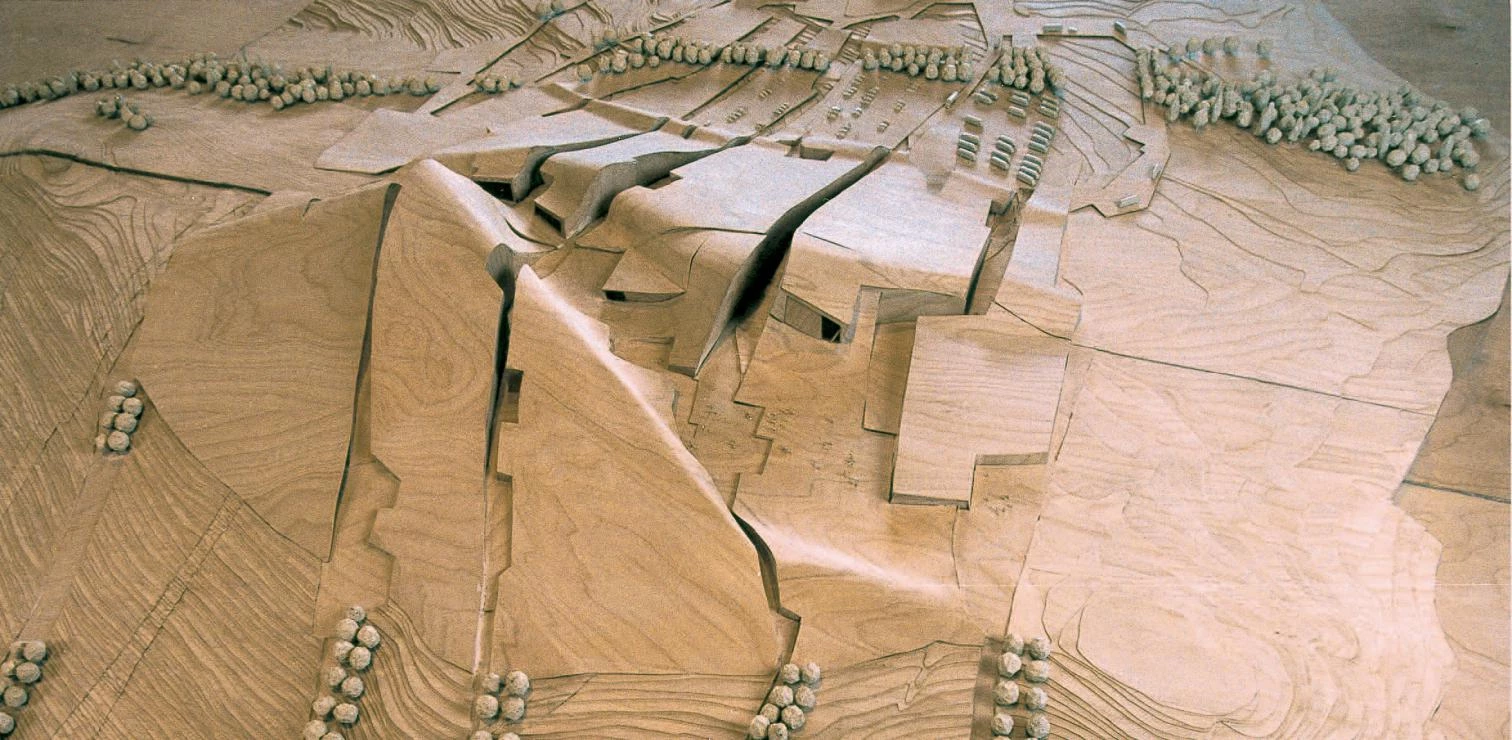

A pilgrim of languages, Peter Eisenman has reached in Compostela the end of a path. All his experiments with form converge in this project that may well be the most important of his career. Facing a holy city, he molds a hill with waves perforated by deep gorges, and below this warped landscape arranges the museums, libraries and auditoriums of a cultural acropolis for Galicia. In this tactile topography, the paths explored by an impatient biography are sheaved together: the obsession with syntax of the seventies, present here in the orthogonal grids that eventually deform in rhythmical distortions; the artificial excavations of the eighties, reproduced through the extrapolation of the old town scheme to the intact site of the new precinct; and the random folds of the nineties, brought to a choreographical extreme in an undulating bark that spreads a stone canopy over the hill.

From his deformed grids in the seventies to his artificial excavations in the eighties and his random folds in the nineties, the formal experiences of Eisenman converge in this project for a cultural acropolis.

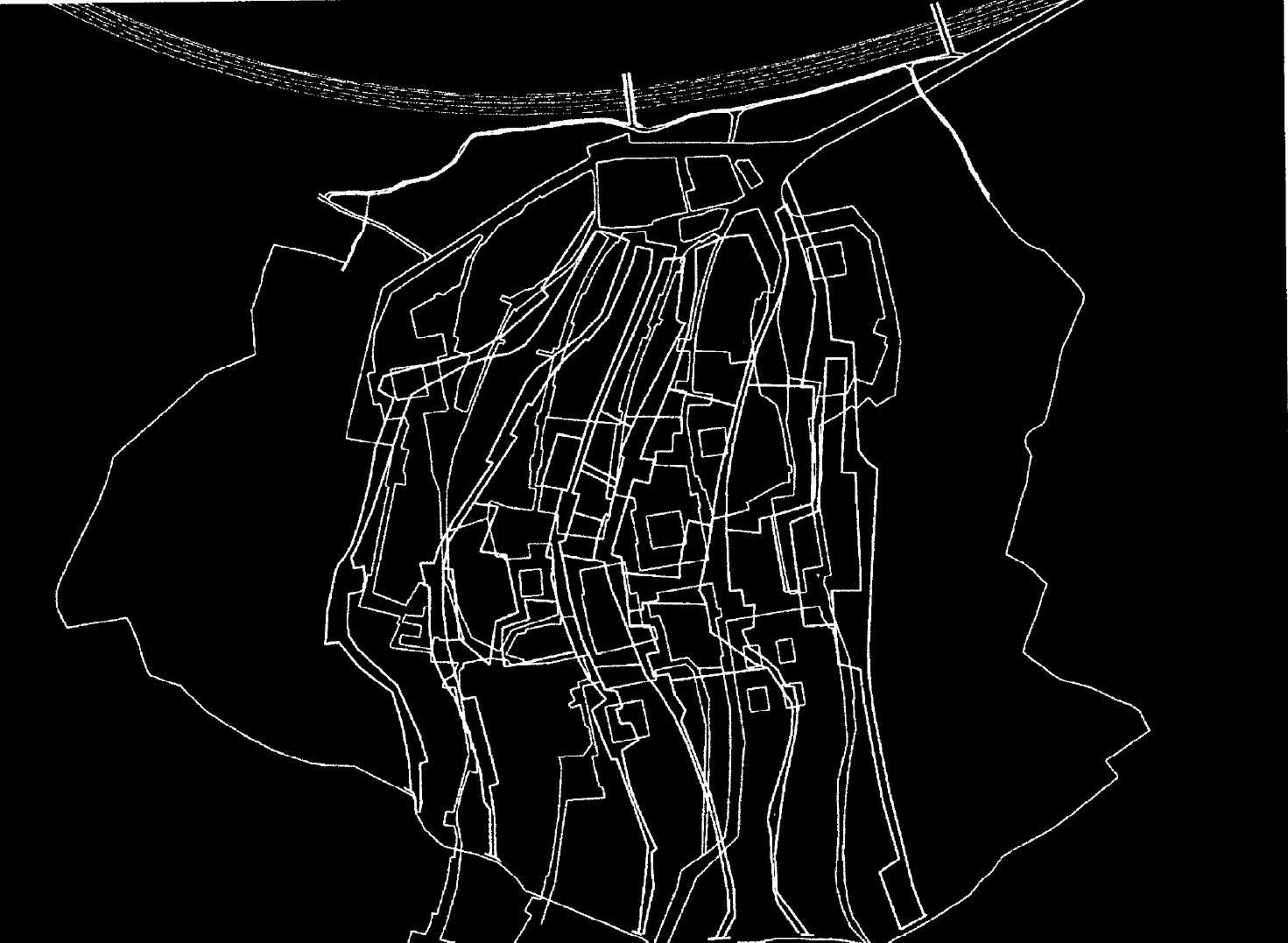

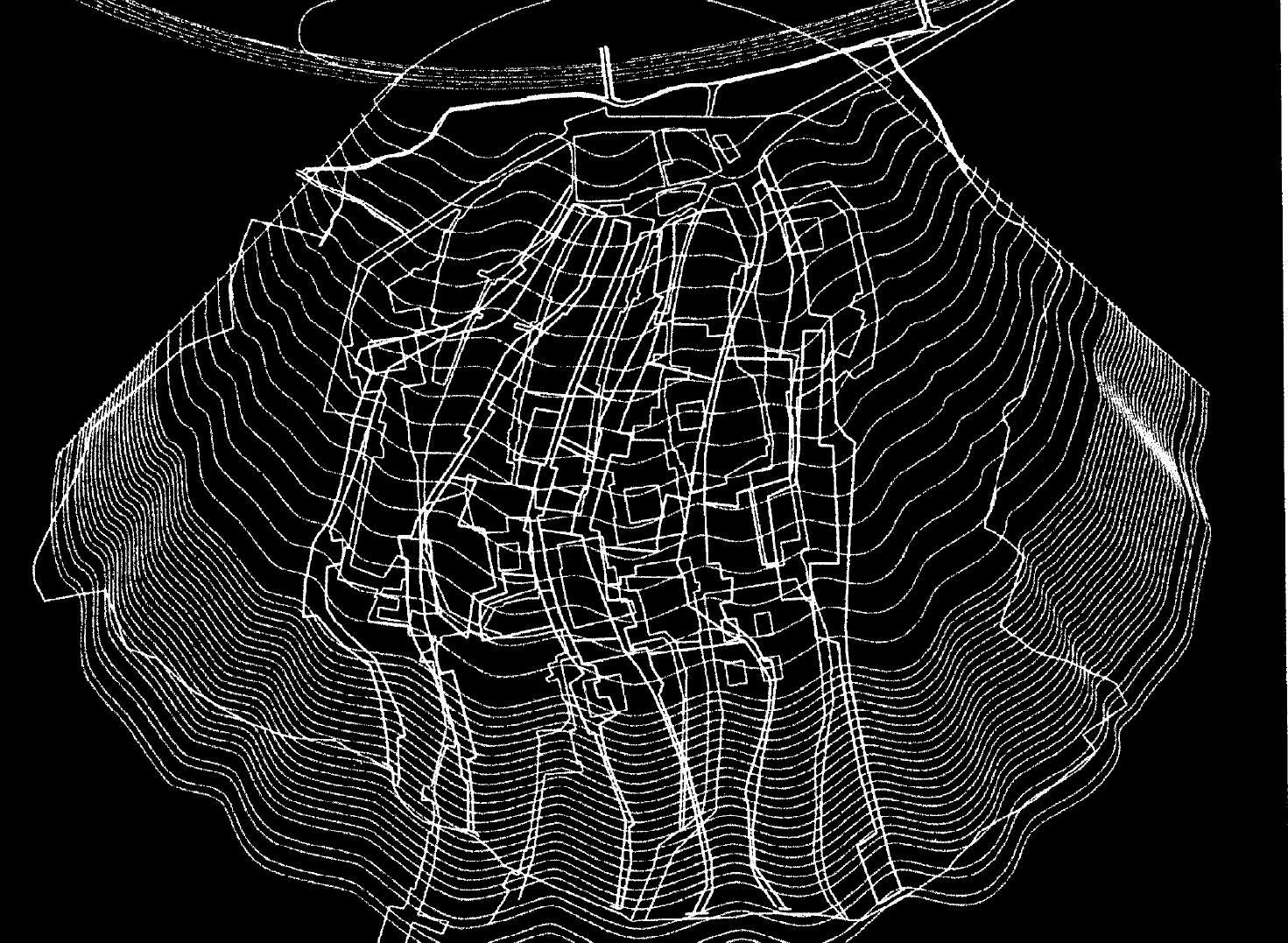

Resembling geological strata on which geometrical cracks have been carved, the volume of the City of Culture unfolds over the terrain like a pliable sculpture, and blurs its limits to blend into a place strung together by five long treelined boulevards. These allude to the same five streets of Saniago’s old quarter, as well as to their traditional extensions with rueiros, and in fact the final shape of the complex springs from the plan of the historic core, which is superposed on the characteristic striated surface of the venera, the scallop shell that is the symbol of the pilgrim’s road to Santiago. Raising its shaken silhouette to the cathedral towers, over the highway that connects Galicia’s Atlantic front, the new City of Culture presents itself as a magic mountain for pilgrims of knowledge.

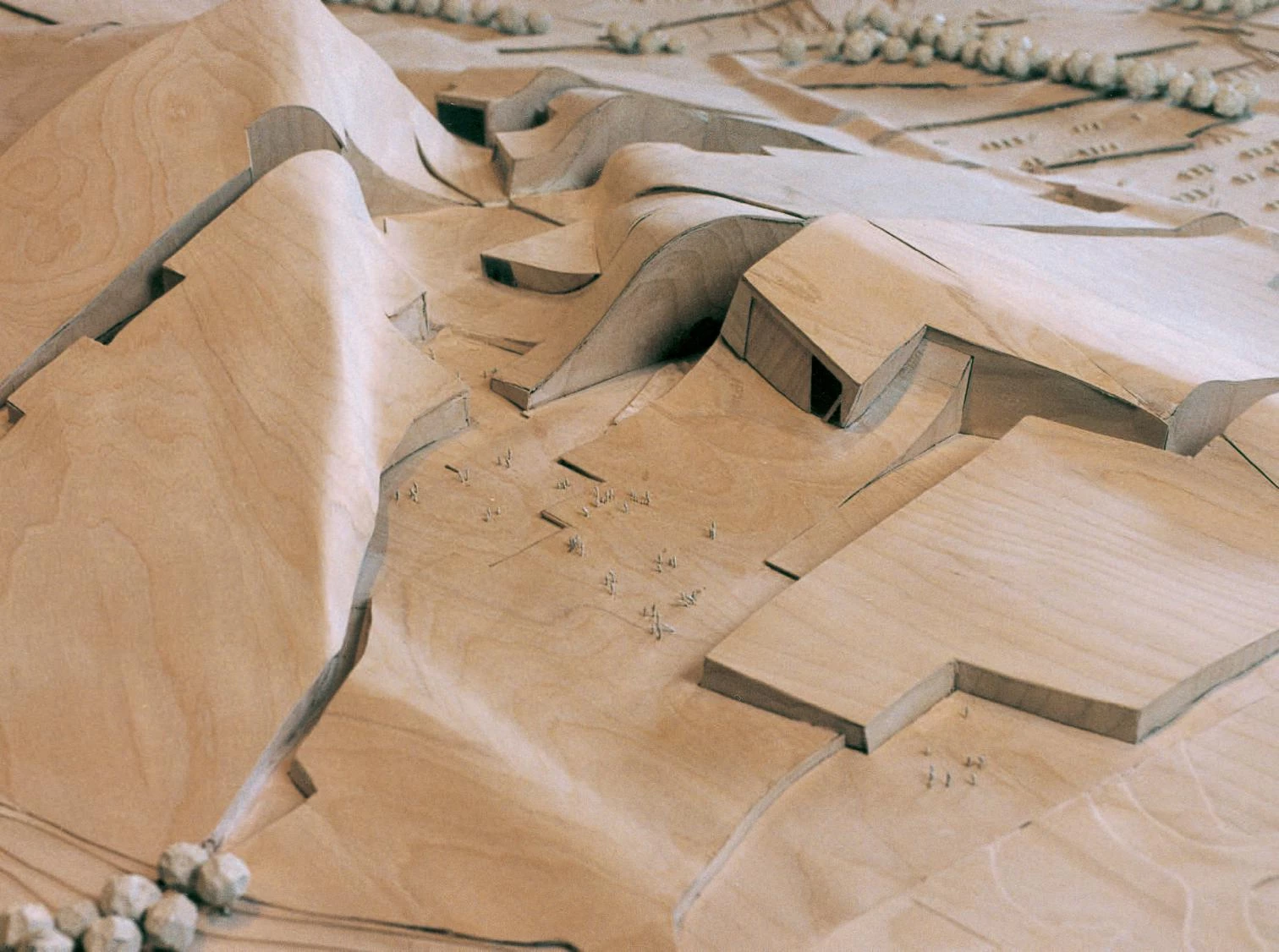

The architect describes the project as a fluid shell, and fluid indeed is the moldable material of this pulsating carapace that spills its waves on the landscape, where they continue to ripple, in progressive deceleration, like a lazy swell of granite; fluid is the clayish plasticity of those roofs rising from the ground, dropping to vanish in the pavement and rising anew, like an arrhythmic heartbeat that invites one to exchange sight for touch; and fluid, too, is the vibrating tremor of the vaginal lips that, though cut up and cracked, evoke the mollusk more than the shell. After all the venera, symbol of Santiago, is first a symbol of Venus, and its etymology, in its ductile receptiveness, echoes feminine shapes. Fleeing from the realm of categorical geometries, this topography also avoids the violence of edges, which only appear where the mass is penetrated by the superimposed urban scheme: a metaphorical and inverted representation of nature’s abduction by construction.

In his passage from edges to waves, Eisenman leaves behind the angular origami of the nineties to explore new ground – territory he had already explored in the Bruges and Manhattan competitions, but never developed with the confident eloquence he has demonstrated in Santiago. Understood by the architect as a way of resolving the opposition between figure and ground, this topographical architecture also revises the limits of what Kenneth Frampton, in the tradition of Semper, likes to call tectonic and stereotomic: the light structure linked to the roof, and the heavy construction in contact with the ground. Simultaneously tectonic and stereotomic, the stone roofs here are assembled and molded, melting into the terrain in a woven continuum that extends over the mountain a thick carpet of granite, in whose sculpted folds the morbid forms of geological erosion are fused with the clear-cut contours of archeological excavation.

The project superimposes the folds of the pilgrim’s shell with the street pattern of Santiago’s historical quarter, fusing the terrain and the roofs with a gesture that blurs the limits between the tectonic and the stereotomic.

Comparing the theatrical pomp of these rotund garments to the calligraphic incisions and sharp edges of previous projects, we note that the architect has abandoned the pleated severeness of Romanesque saints for the undulating tunics of Gothic angels, the diagrammatic facades of Renaissance palaces for the volumetric roar of Baroque altar-pieces, and the faceted geometry of the F-117 Nighthawk for the warped horizontality of the B-2 Spirit. By onomastic coincidence, Peter Eisenman reconciles tectonic iron with stereotomic stone, and his drift from syntactic grids to sculptural volumes may also be a shift from surname to forename. But it also happens that the architect’s brother is a historian, according to whom the James/Santiago we associate with the venera and believe to be buried in Compostela is not James the Great, but James the Lord’s Brother – in his opinion the only James of the New Testament to have really existed, and the legitimate successor of Jesus, before Peter, as head of the Christian Church.

This unexpected coincidence closes a fraternal virtuous circle, with a Jew entrusted with the construction of a sanctuary of culture in the vicinity of the tomb of the rival of Paul, he who made the new religion universal by sectioning its Jewish roots. The tomb of the Apostle may well have been but a brilliant Medieval invention seeking to bond northern Spain to European Christendom; Galician president Manuel Fraga may perhaps not see himself as the successor of the cathedral’s builders; and Robert Eisenman’s story about James may indeed be no more than a hypothesis made of the flimsy wicker of erudition and fiction. But in the most fmous page of À la recherche du temps perdu, Proust notices that the wrapping of his madeleine cake reproduces the fluted fan of the pilgrim’s shell, and surely the pleasure produced by such a magical, mythical undulating form heralds a happy ending for this architectural pilgrimage from grammar to memory, from edge to wave, and from eye to skin.