The Panda and the Dragon

Is the Middle Kingdom panda or dragon? Is it the kind bear that fascinates everyone or the mythical animal that everyone respects and fears? Probably, China is at once panda and dragon: a voracious mammal that needs to consume thousands of bamboo shoots a day, and a soaring reptile that extends its presence to the corners of the world. Both the emblem of zoos worldwide and the leading character of so many legendary episodes are equivocal icons: the sweet and cuddly panda is in fact a cellulose-shredding machine, while the fierce dragon of Western mythology is in the East a protecting and benevolent force. But these ambiguous symbols suit a country that must supply the food, raw materials and energy demanded by a population of 1.3 billion, and to do so it needs to multiply its influence and display its soft power around: if it wants to feed the panda it must walk the dragon.

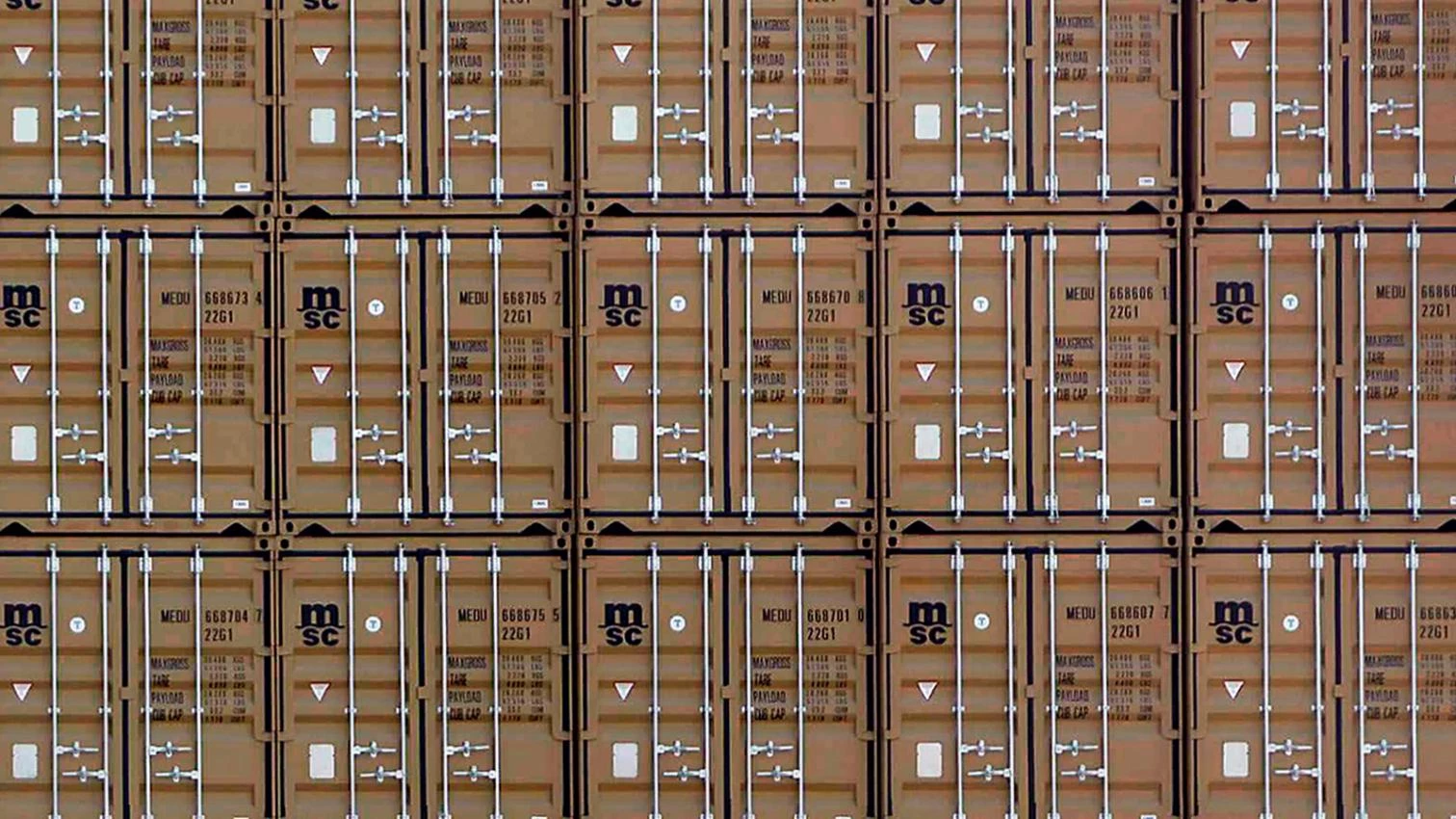

The huge, unprecedented effort to take hundreds of millions out of misery has often been abrasive and ruthless, and this has been expressed in the abrupt transitions from country to city, and in the desolate aspect of so many of the new urban landscapes. These environments, however, are the stage of an emerging prosperity that steers the country towards the role of hegemonic power, with an increasing and already overbearing presence in Asia, Africa and Latin America. China has become the first trading world power, with six of the nine largest commercial ports and half of the container traffic. The trade flows from Asia explain the priority given by the European Union to the railway infrastructures of the Mediterranean Arch, because the transportation volume in that sea already triples that of the Atlantic Ocean, reversing the Western orientation dominant during the last five centuries.

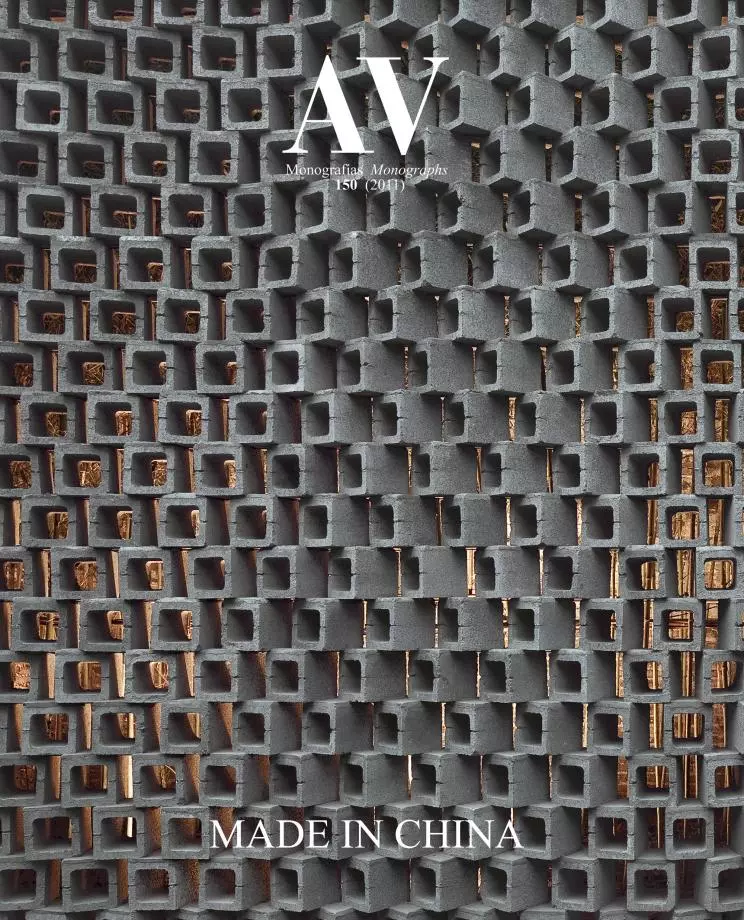

China is today the main moneylender, exceeding the World Bank, and in its expansion it also offers technology and human capital, thus becoming a powerful development agent in many countries. It does so, indeed, to obtain the soy, minerals and oil its hungry panda needs, but it does so deploying a kind and industrious dragon. Its state capitalism has become a model for many, even if the panda’s habitat is still deficient. But ‘Made in China’ does no longer mean cheap and slovenly mass production, and in the field of construction there are many examples, inside and outside the country, that show the quality of what can be accomplished when work ethic is combined with the pursuit of excellence. When seven years ago we published ‘China Boom’, most authors were foreign; today the list is Chinese only, and that says a lot about the achievements of the country of the panda and the dragon.

Luis Fernández-Galiano