Architects are from Venus

The relationship between architects and politicians is both close and conflictive, as can be seen in China, Russia and the Gulf, or in the latest Spanish rows.

Politicians are from Mars, architects are from Venus. To paraphrase the neo-conservative Robert Kagan, whose Of Paradise and Power explained the differences between Americans and Europeans in those terms, the current conflicts between politicians and architects in Spain – from Juan Navarro’s firing in Madrid or Santiago Calatrava’s court case in Bilbao to the parliamentary investigation of the New Yorker Peter Eisenman’s project in Santiago de Compostela – could be attributed to the different position each group takes in the theater of shadows of social representation. While politicians struggle for power through campaigns glazed with the vocabulary of war, architects inhabit an amniotic paradise of sensual beauty and symbolic seduction. When these parallel universes meet, architecture becomes the repose of the warrior, the object of desire of the politician succumbing to the disorderly appetite of the cupiditas aedificatoria, or the wet dream of the statesman determined to leave as big a mark on geography as on history. But the paradise of political power and the power of the architectural paradise are night trains crossing one another, fleeing phantoms that vanish like our remembrance of dreams, and only rarely do political will and architectural imagination come in tune to produce memorable monuments: Le Corbusier’s Chandigarh exists thanks to Pandit Nehru, Oscar Niemeyer’s Brasilia cannot be separated from the figure of Juscelino Kubitschek, and even Frank Gehry’s Guggenheim would never have come to pass without the go-ahead of Xabier Arzalluz.

Nicolas Sarkozy initiated his presidency of France with a family portrait that gathered the stars of contemporary architecture.

In any case it takes two to tango, and the history of the architecture of the last century is sprinkled with the names of sponsors and clients who knew how to team up with their architects. Many were magnates with cultural sensibilities or a desire for recognition, among them Frank Lloyd Wright’s Edgar Kaufmann or Hilla Rebay, Mies van der Rohe’s Phyllis Lambert, Louis Kahn’s Paul Mellon, or Renzo Piano’s Dominique de Menil; it is partlyto the likes of these that we owe many of the century’s masterworks in the United States. In Europe, meanwhile, public patronage was more significant, and politicians were protagonists to such a degree that we can speak of Mussolini’s Rome or Mitterrand’s Paris, drawing an arc that stretches from the totalitarian utopias of Hitler or Stalin (but also of the early Franco or the late Ceausescu), to the grand urban projects of the democracies. These profane marriages between architect and politician now happen in all corners of the world, and so it is that Vladimir Putin’s Russia or Nursultan Nazarbayev’s Kazakhstan compete with the Gulf emirates or Olympic Beijing in using iconic works to flaunt their economic push, varnishing their autocratic regimes with the spectacle of architectural celebrity.

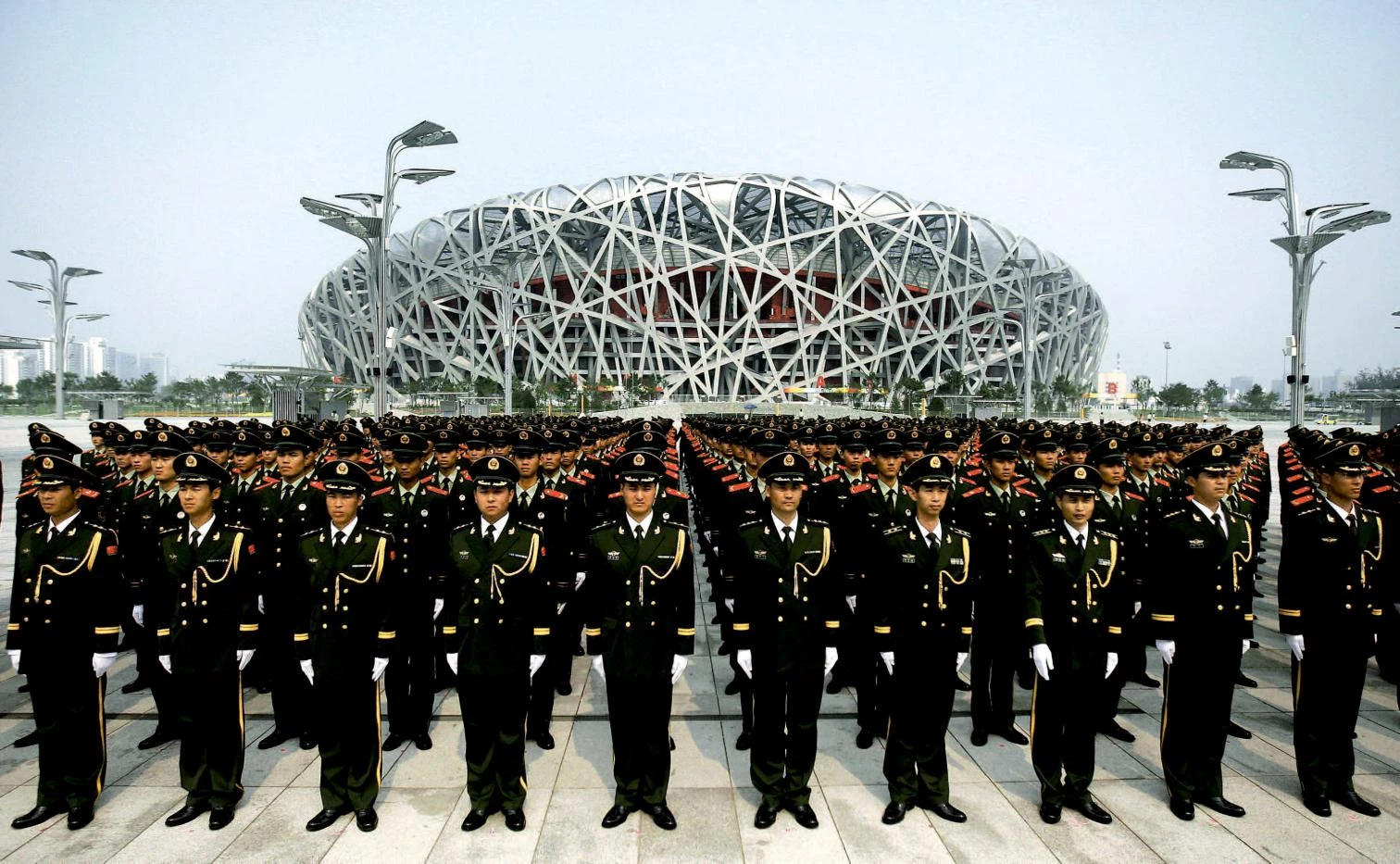

The National Stadium for the Olympic Games in Beijing, designed as a nest by the Swiss Herzog & de Meuron, has become a symbol of the country, immediately reproduced on bills, where its image replaces that of Mao.

To be sure, the architects who are erecting milestonesfor the eastern boom are the same ones who not long ago met with Nicolas Sarkozy at the Elysée Palace for the family portrait of a French presidency that has the aim to carry out radical reforms while selecting a dream team of builders who will ensure it a place in history. The coincidence should not come as too much of a surprise, for in these times of weak ideologies architects have made realpolitiktheir religion and rarely will they refuse a project for political motives or ethical reasons. Even inmore polarized periods of history, the great masters have sought to adapt to the climate of the moment, and just as Mies built a monument to Karl Liebknecht and Rosa Luxemburg with the hammer and sickle only to later try to please the Nazis by designing a pavilion with the swastika, Le Corbusier unflaggingly tried to be the architect of Marshall Petain’s collaborationist regime and yet after the war ended up building the Unité d’Habitation under the auspices of General De Gaulle’s first government. With such precedents, the flings of today’s architecturalstars seem like venial sins, if indeed we can consider venial the current situation of human rights and democratic liberties in China, the former Soviet republics, or the emirates of the Gulf.

Today’s architectural elite shows as little attachment to ideological postures as professional football players do to the T-shirts of their clubs. It offers itself to the highest bidder and its integrity takes refuge in artistic excellence. The Calatrava case illustrates this better than any other. When his native Valencia made a right turn during the second half of the 90s, the architect had no trouble modifying his colossal City of Arts and Sciences project, replacing a titanic tower with an auditorium, to accommodate the priorities of the new powers that be. But when the same council of Bilbao who had commissioned him to build a footbridge authorized grafting on it another designed by Arata Isozaki, Calatrava resorted to the courts demanding respect for his intellectual property. Socialists, conservatives, what difference does it make? The Valencian’s sculptural forms can be put at the service of either just as they were emblems of both the Lisbon Expo and the Athens Olympics, and yet a handrail can be a casus belli, an offense that turns Venusian architects into bellicose Martian litigants.

The titanic scale of the tents by Norman Foster in Astana and Moscow show the huge economic power and the yearn for recognition of Nursultan Nazarbayev´s Kazakhstan and of Vladimir Putin´s Russia.

The latest rows in Madrid and Galicia are even more puzzling. In the capital, the Teatro del Canal was started by the former regional president Alberto Ruiz-Gallardón, and reluctantly continued by his successor, Esperanza Aguirre, who, instead of making it her own, with some changes in the program, which is the cynical but efficient usual thing to do, chose to make a dead end of it, maybe in the hope that her predecessor’s musical and theatrical ambitions would wilt, in the process running over a self withdrawn architect who crosses the street of politics without remembering to look. In Santiago de Compostela, the electoral defeat of the regional president Manuel Fraga left half-finished the work he probably would like to be remembered for, the City of Culture of Galicia, and his successors in the region’s government play a Hamletian “she loves me, she loves me not” that can only lead them to make the complex theirs and give it a happy ending, with the amendments and alterations they deem necessary. For after all, the project’s eventual failure or success no longer belongs to Fraga, but to those now occupying the Pazo de Raxoi. The Scottish Parliament also carried out an enquiry of its own seat, designed by the prematurely deceased Enric Miralles, and censure of the budgetary overflowing did not prevent the work from capping Britain’s most prestigious architectural award, the Stirling Prize, and becoming a symbol of Scotland’s rise, as is sure to happen in Galicia with the City of Culture if those responsible for it know how to bring it to a satisfactory conclusion.

All great works are in the end controversial, and all exceed the limits of legislative periods, therefore risking political change. The Barcelona Olympics, the Seville Expo, the Guggenheim-Bilbao or the Prado Museum, the AVE high-speed train stations, or the new generation of airport terminals: of these works which have transformed the country’s territory or its image, not one was executed without tough political and media confrontations. But architects are from Venus, have no power, and can only hope to survive in the battlefield of partisan conflict if the contenders respect them the way they do the Red Cross, though even then architects will always be exposed to a stray bullet. As for the politicians from Mars, whether or not they succumb to the lure of architecture, they should understand that it is not necessary to shoot the pianist, who will always be there to play the song they request. The architect materializes the sultan’s dreams, but is only a eunuch in his harem. Though it is also true that, blinded perhaps by their proximity to power, architects often imagine themselves building a work of their own, forgetting that they are hired to dream the dreams of others. As in the Fernando Arrabal theater play, and contrary to all evidence, every morning the architect expects the emperor of Assyria to offer himself for breakfast.

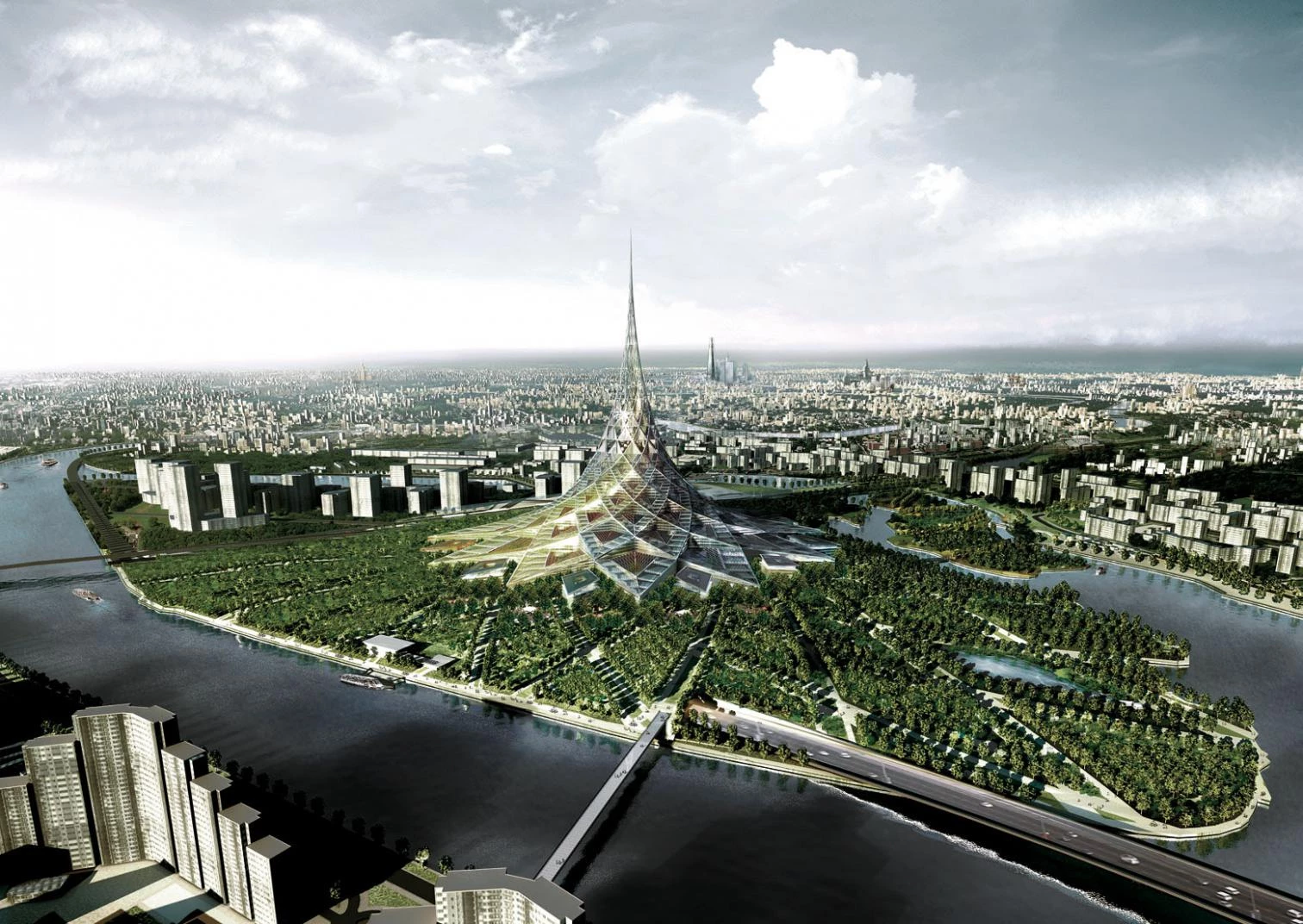

The Persian Gulf also promotes signature architectures,whole cites such that by Foster in Abu Dhabi and by OMA in Ras al Khaimah, or large urban projects as the one by the same Dutch team in Dubai.