In an unusual speech, Chinese President Xi Jinping condemned weird architecture, and many in the West listened in agreement. However, his call for pleasant art (“sunshine in a blue sky and a breeze in spring”), socialist and patriotic, has also sparked up the recent directive of the communication media authority that imposes stints in the countryside for intellectuals and artists, and in this case the echoes of the Cultural Revolution promoted by Mao Zedong from 1966 to 1976 have raised all alarms. Reeducation through immersion in the peasant world left a lost generation in its wake, but the month-long stays in rural zones or mining areas for employees of public press, radio, film, and television companies seem insignificant compared to all the drama that marked the exodus of China’s urban youth almost half a century ago. At any rate, Xi’s aesthetic opinions can set the creative pace of a country that harbors a formidable art market and which in the past decade has been a privileged stage for iconic architecture.

He who is the most powerful man in China since Mao has launched an ambitious agenda covering everything from economic liberalization and war against corruption to the revision of one-child-per-family policies and the regulation of internal migrations, and now comes the turn of the ideological realm of the arts, where Xi advocates restoral of the ‘cultural hegemony’ that Gramsci considered indispensable to successful political struggle. In the context of an art and literature symposium held in Beijing on 14 October, Xi spoke for two hours about architecture and art having to “inspire minds, warm hearts, cultivate taste, and clean up undesirable work styles,” calling on the nation to avoid mercantilization and “spread contemporary Chinese values, incorporate traditional Chinese culture, and reflect the aesthetic interests of the Chinese people.”

Already seen in China as the most important official take on art since Mao’s mythical interventions at the Yan’an Forum in 1942, Xi’s discourse did not hesitate to offer examples of what he judged as ‘weird’, centering his critiques on the building raised by Rem Koolhaas in Beijing as headquarters of the state television network CCTV, and a bridge in Chongqing which in shape and color resembles female genitalia. What some have named Xi’s ‘Maoist turn’ has been promoted on the visual prominence of the examples given, provoking defensive reactions from architects like Koolhaas himself (“CCTV is a very serious building … Chinese culture and Chinese architecture will benefit”), or from developers like Pan Shiyi, whose Soho projects with Zaha Hadid have been dismissed as weird by the pro-government Global Times.

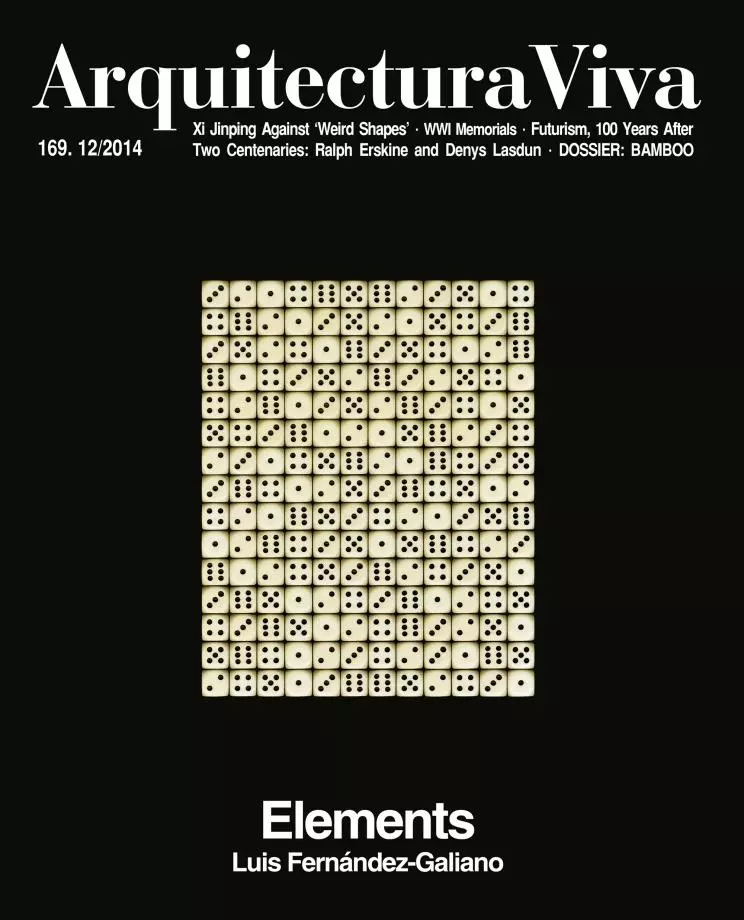

In his rejection of extravagance, Xi is in tune with a climate of opinion that the crisis has spread throughout the world, and which among other things will increase respect for heritage, an area where China’s vigorous urban development has had devastating consequences; in this convergence it is significant that the author of the building most criticized by Xi has stormed the Venice Biennale with an exhibition that upholds the fundamentals of architecture over the variable languages of architects. But in the insistent assertion of Chinese culture and values lies a sublayer of nationalism that is cause for alarm, taking place, as it does, in a geopolitical context of tensions between the great powers in the Pacific, and of Chinese economic expansionism in Africa and Latin America. Seen from Europe, perhaps no more than a peninsula of Asia, Xi’s calm and patriotic aesthetic perhaps warrants as much sympathy as apprehension.