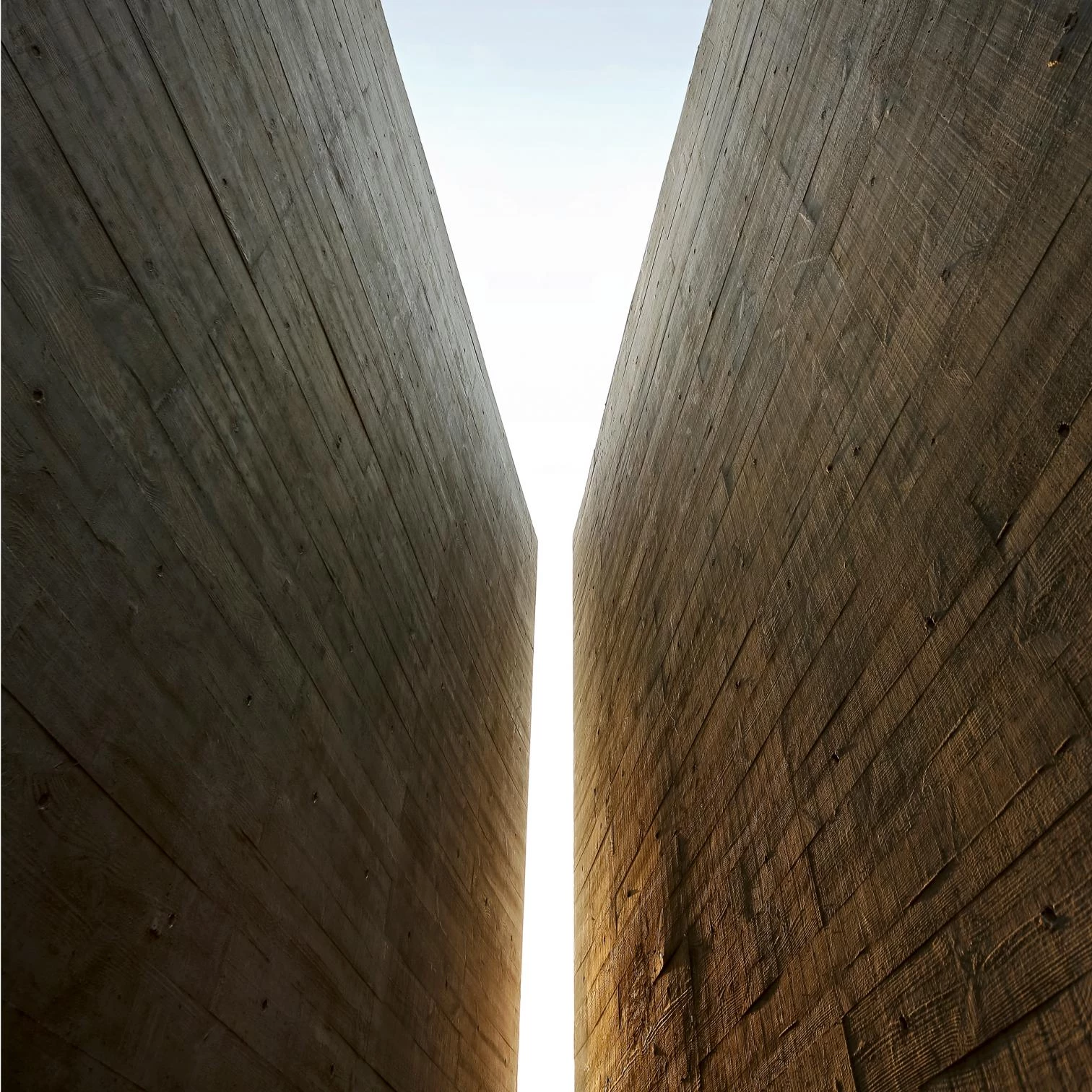

Gong Dong builds with light and with matter. The Beijing architect was dazzled by light on the other side of the Pacific, through his post-graduate training in Illinois; he built luminous and somber works on the coasts of China and deep in the countryside; and brings that Eastern light to European lands, to the Venice Biennale by the Adriatic or to the forums of this puzzle of nations. Light thus comes from the East, but a light trapped in the matter of buildings that are firm and dry, lyrical in the poetry of perception and pragmatic in the prose of function, which blend into the landscape and at the same time assert their presence on it, respectful towards the existing and propositive in front of the obsolete, rooted in tradition and bent on invention. With feet on the ground and head in the clouds, this oxymoronic architect goes back to the past to prefigure the future, shaping light with matter and matter with light.

Natural light cuts like a knife the volumes of his seashore library, which opens the books to the beach through horizontal windows that echo the line of the horizon, and that creates meditation spaces where the openings enhance volumes and textures. And artificial light, filtered through lattices, spreads from the pavilions of his hotel on the Li River valley, turning them into light lanterns fractured by warm bamboo cascades, as fractured is the unique relief of its karstic landscape. Be it natural or artificial, light rules both the low-lying library by the sea and the sloping roofs of the hotel that takes shelter in its mountain cradle, phenomenologically interpreting antithetical natural environments, and showing its reverence towards landscape with materials that invite handling and touching through the paradoxical tool of the gaze, because this is an architecture that does not flatter vision, but guides the eye to the hand.

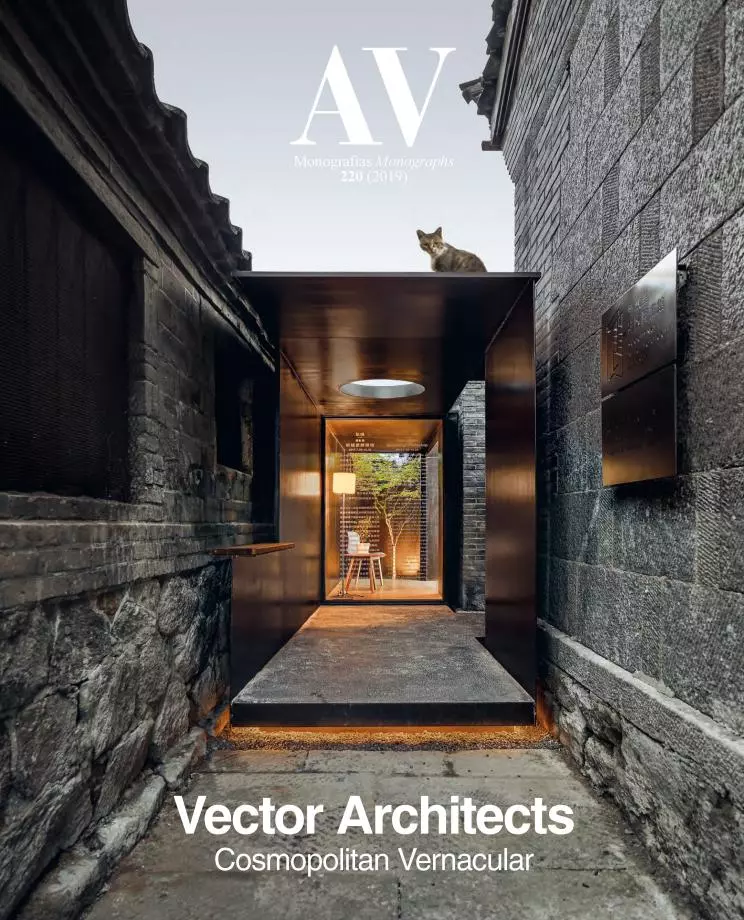

Combining nature and artifice, fusing memory and need, and grafting the buds of the contemporary in the aging tree of heritage, the work of Vector Architects is representative of a generation that does not wish to import iconic forms from international labs, or become self-absorbed in the disciplined extension of a millenary heritage, because they build with the ease of those who know their place in the world. When Gong Dong faces the dialogue with the existing, his palette of materials and lights is not used to stridently show the singularity of the new, or to tamely extend the frozen narrative of the old: the versatility of his compositive and constructive resources is used to blur the boundaries between what is already there and what is added, establishing a conversation that makes continuity the guiding thread, so that the work is both of our time and timeless, belongs to the world and also to the place.