The 2008 Olympic Games symbolically endorse China’s protagonism in today’s world: the planet’s largest nation flaunts its economic power and organizational skills through a sports, political and urban event that puts the ‘Middle Kingdom’ at the center of the global stage. At the same time, the colossal structures raised for the occasion – designed mainly by foreigners – turn Beijing into a rich laboratory of architectures that permit taking the temperature of a feverish discipline. Rising over a landscape of fast urban growth and vast destruction, which has led to the disappearance of the traditional city of hutongs and courthouses, the five major public works – to which we add here a private development as an example of the country’s present building boom –are emblems of China’s rise, but also serve to illustrate the current architectural debate.

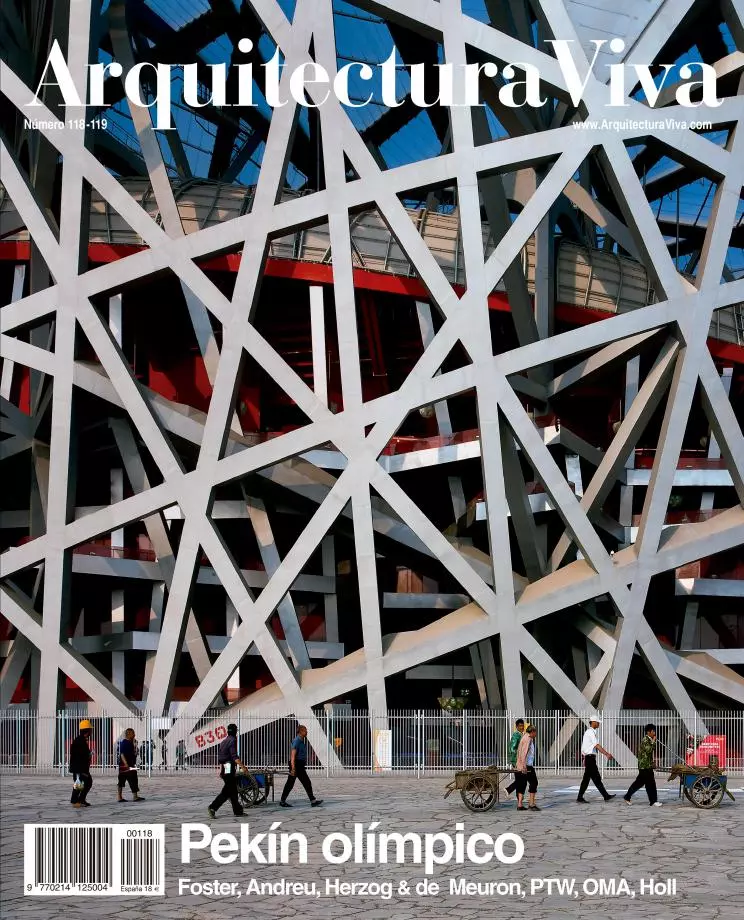

The airport by Norman Foster, with its exact diagram of flows and an unexpected lightness in what is after all the largest building in the world, shows the stubborn resilience of modernity; a design approach that is also present in the National Theater by the polytechnicien and also airport architect Paul Andreu, whose pearly ellipsoid of glass and titanium over the water inevitably evokes that French geometric monumentality that leads us back to Boullée. Postmodern in their epidermic representation of random meshes are, in contrast, the two large sports venues of the Olympic Park: the great stadium by Herzog & de Meuron, turned into an instant icon of the Games – both techtonic and pyrotechnical –, through a huge skein that knits the steel to conform what has been described as an intimate and titanic nest; and the appealing swimming pools by PTW, known as the water cube because their prismatic precinct is clad in a translucent skin of soft ETFE bubbles. Midway between epithelial postmodernity and heroic modernity are the two high-rise projects, the striking logo drawn up as a folded frame by OMA to serve as headquarters of the CCTV, with its calligraphic expression of the structural stresses and its gymnastic, formal displays in a tradition that goes from the Wolkenbügel to the Max Reinhardt Haus, and through the KIO towers; and the Linked Hybrid by Steven Holl, eight intertwined towers that unite the metaphysical abstraction of a residential still life and the technical dynamism of their industrial footbridges, in the wake of those we admire in the Van Nelle or the Pompeia factories.

This foreign legion of excellence – only the Chinese Ai Weiwei appears prominently in the credits of the stadium project – has tried to interpret the needs and idiosyncracies of the country, but has also used this unique occasion to bring to China the present dilemmas of western architecture. European for the most part – British, French, Swiss, Dutch and even German if we were to include the urban axis by Albert Speer Jr. –, with the testimonial presence of an Australian and an American team, this gathering of talent significantly excludes the Asians – surely because it was out of the question to grant major commissions to the Japanese, by far the continent’s most experienced –, but still it is representative of the moment: the Olympic Beijing speaks as much about today’s China as about a global architecture hesitant between function and spectacle.