On 24 October, the Barrié de la Maza Foundation in La Coruña opened the exhibition ‘Rafael Moneo: A Theoretical Reflection from within the Profession’. Conceived as a journey through the archives of his practice, this is the first retrospective show on the oeuvre of the Navarrese architect.

The exhibition recounts the trajectory of an architect who has sought to define an approach to architectural design that, amid the changing conditions of our times, is anchored to a stable disciplinary base, taking the difficult position of defending architecture as culture and as a specific form of knowledge. But besides laying before us the work of a particular architect, the exhibition gives us a good part of the history of recent architecture as seen through his eyes. From the organicist and structuralist tendencies of the 1950s and 1960s and the Italian discourses on the city to the theoretical anxiety of American East Coast architects of the1970s and 1980s and the emergence of the global ‘star system’ in the 1990s, the Moneo retrospective shows how the architect has resisted, reflected on, and assimilated these forces and given form to a cultural reflection of his own. The selection also puts emphasis on the importance of drawing in his lifework, for him a fundamental tool in both his work process and the formulation of his thinking.

If I had to decide on an appropriate tone for presenting the architecture of Rafael Moneo, it would be more epical than lyrical. The reason for this is not the alleged heroic nature of his work, but rather the fact that epic artists always need to nourish their work with knowledge and experiences they have had, with the facts and circumstances they have managed to accumulate in the course of their lives. The more they know, the more capable they are of creating a narration of their own. Moneo’s work unfolds in a similar way, evolving and transforming as one of the most accurate dioramas of his times, places, and circumstances.

The Formative Years

As a young architect, Rafael Moneo (1937) began his career with an organicism characteristic of the ‘Madrid school’: a functionalist architecture seeking expressive forms without deviating from the modern logic of construction honesty. Working with Sáenz de Oíza on Torres Blancas (1958–61), choosing Jørn Utzon’s studio in Denmark as next workplace and participating in the project for the Sydney Opera House (1961–62), and collaborating with Fernando Higueras in the Restoration Center (Spanish National Architecture Prize 1961) were all in line with this tendency.

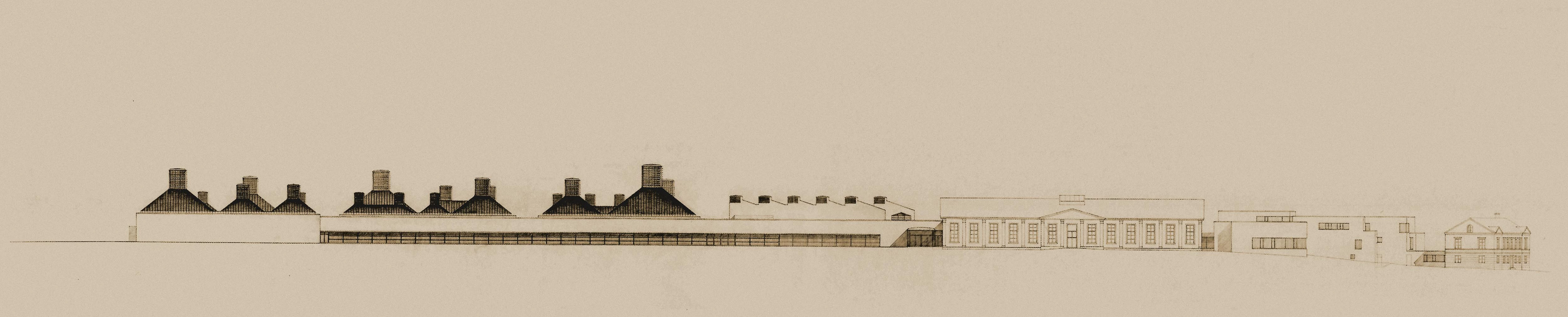

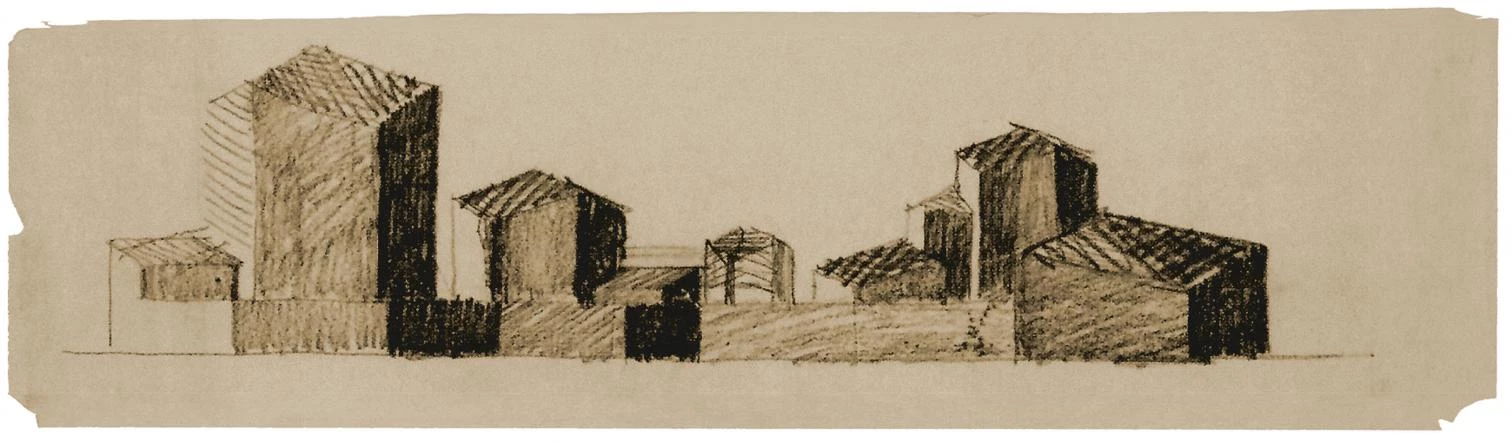

It was hence this organicism, which endeavored to bring back a true modernity inspired in Wright and Aalto, that could be discerned in Moneo’s early designs, such as his entry to the Madrid Opera House competition (1964), the Diestre transformer factory (1964–7), the Gómez-Acebo house (1966–68), or the Tudela schools (1966–71). Sometimes this organic sensitivity interwove with a systematic structuralist approach, also typical of the period, as in the enlargement of Pamplona’s bullring (1966–67) or the competition for Amsterdam’s City Hall (1967–68).

But Moneo never altogether succumbed to the Madrid school, and this was already evident in his 1962 proposal for the broadcasting station on the Plaza del Obradoiro. Although the project has aspects of Madrid organicism, filtered by a personal expressivity, the delicate articulation of pieces in relation to the context, its modest scale, and the carefully made construction choices throw light on Moneo’s early sensitivity to urban context and his belief in architecture taking on its own circumstances. The Obradoiro project brought him a fellowship at the Spanish Academy in Rome (1963–65), although the Italian intellectual discourses would not take shape in his work until the end of that decade.

A Personal Expression

At the end of the 1960s Moneo focussed on preparing for an academic competition. This was his first opportunity to put order to his architectural thinking. The result was a program for teaching design that earned him the Chair of Elements of Composition at the School of Barcelona in 1970. In this program Moneo situated history at the center of his approach to design, considering it a body of knowledge that equips architects with a set of solutions already tested by others. This posture would be reflected in his work as well, and the direct use of solutions previously used by Asplund, Gardella, Terragni, Sullivan, and even contemporaries like Rossi, Venturi, or Stirling would begin to be recurrent in his projects.

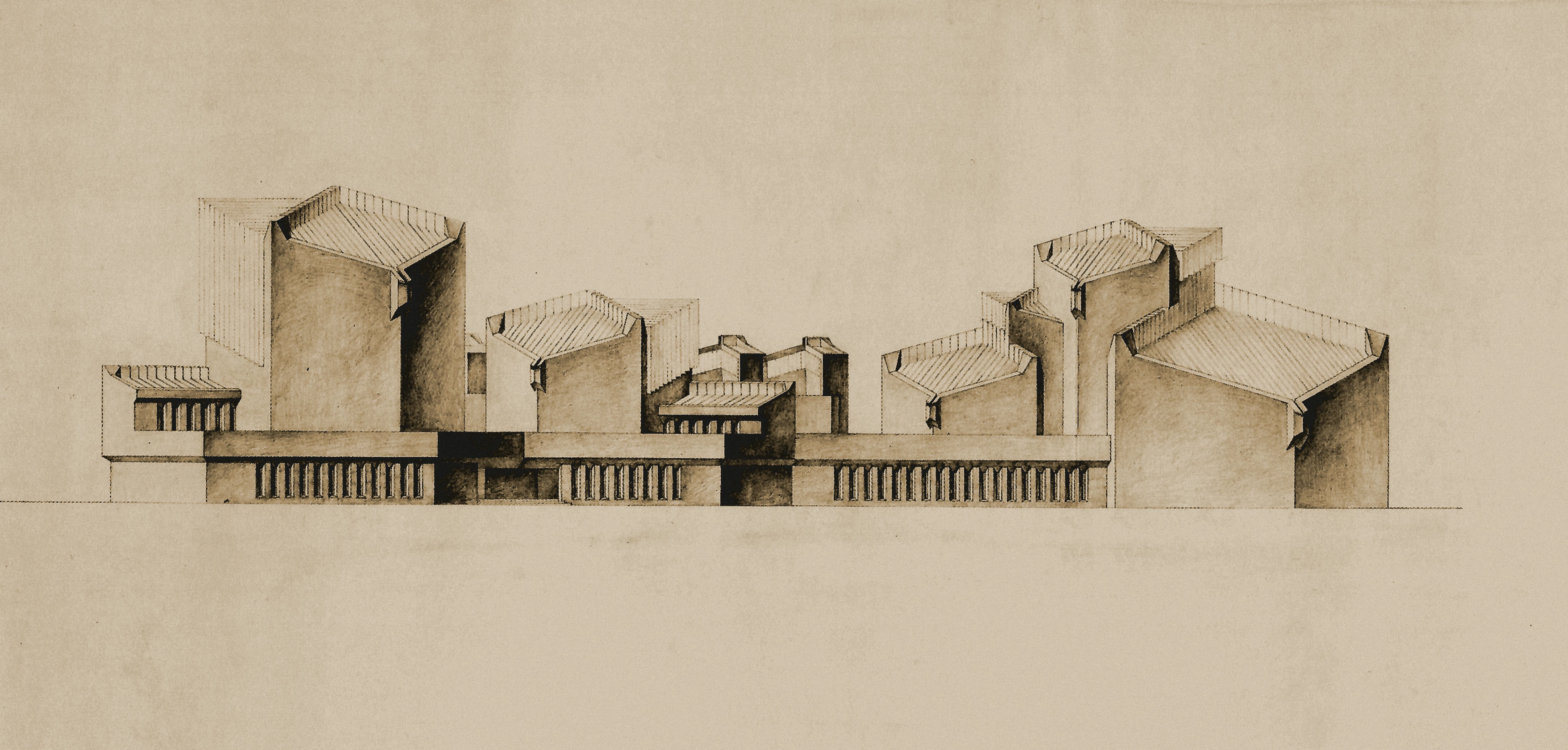

The new method also involved questioning the formal coherence of the Madrid school’s organicism, as well as reconsidering composition as a design tool with which to express a kind of architecture made of different parts. Besides composition, Moneo would require a new theory of architectural form, of the kind that could give his buildings a structuring principle when atomized into parts. This structuring principle would be put to question through the idea of typology and in essays like ‘On the Concept of Type’.

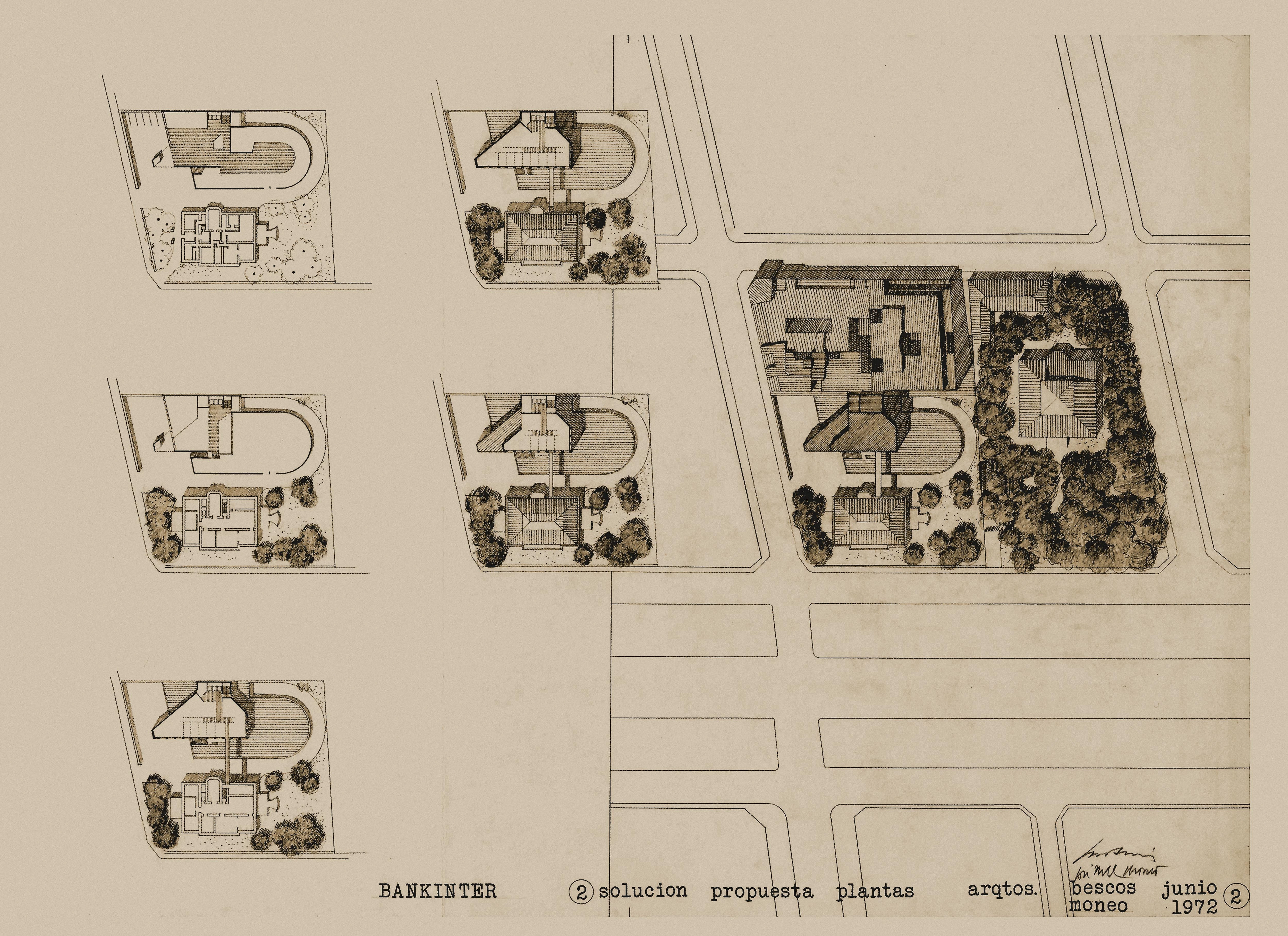

The inicital organicism of projects like the Broadcasting Station in Santiago gave way to a language of Moneo's own, attentive to context and types, as in Bankinter or the urban proposals for Zaragoza and Eibar.

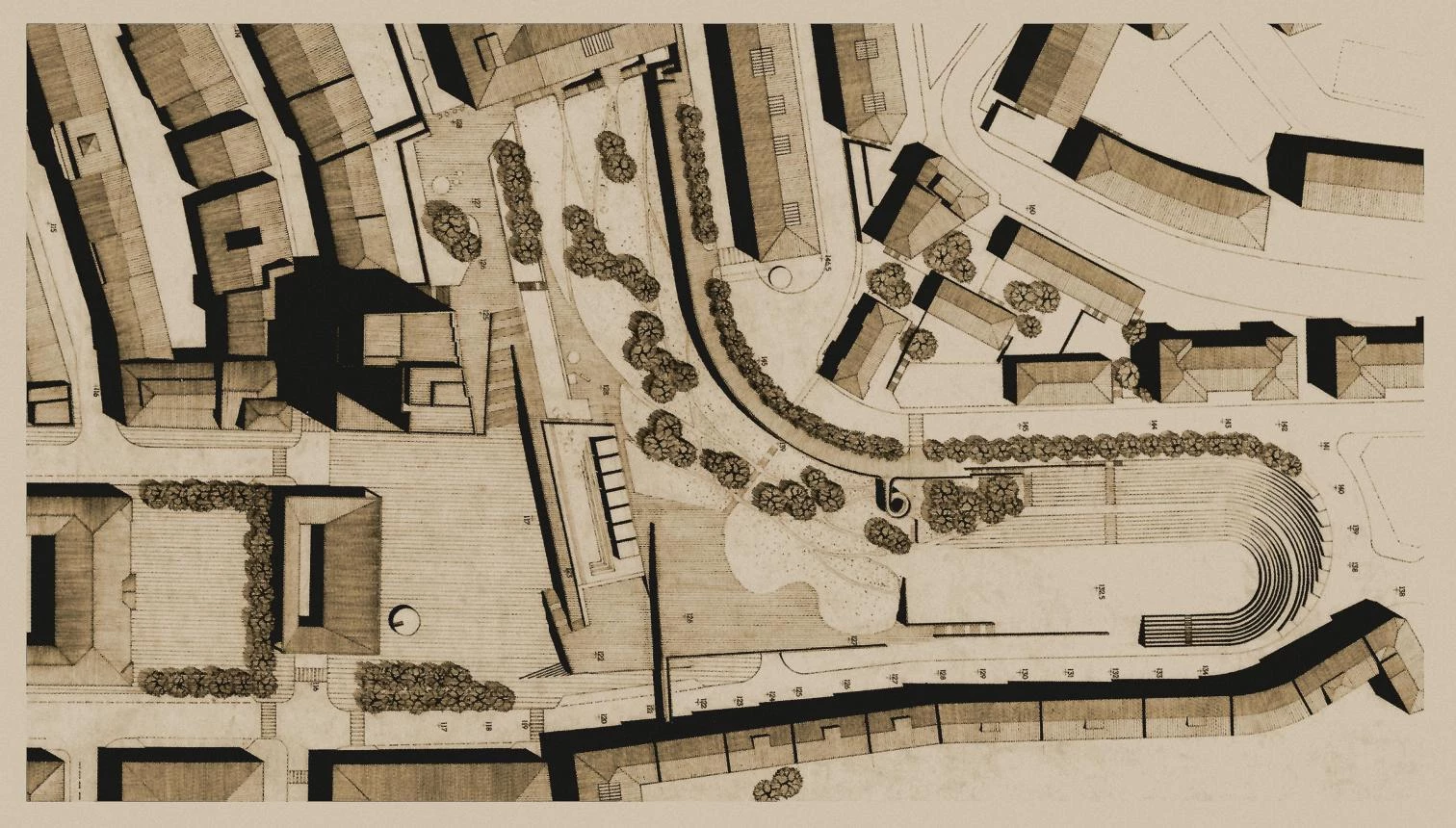

Moneo’s relationship with the Barcelona urban planner Manuel de Solà-Morales was also key to his assimilation of Italian discourses on the city. Their collaboration began with a proposal for redeveloping the old quarter of Zaragoza (1969–70).

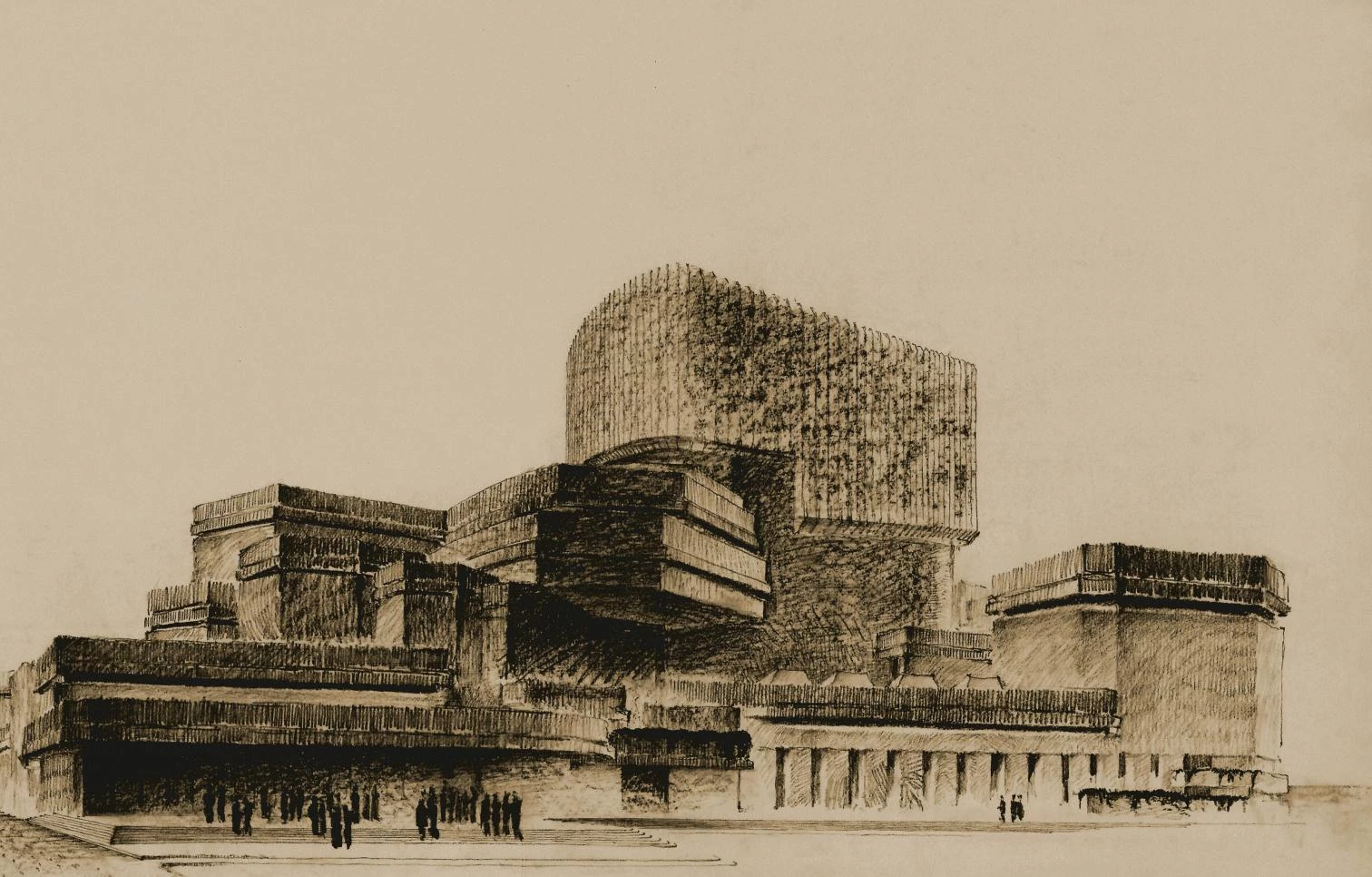

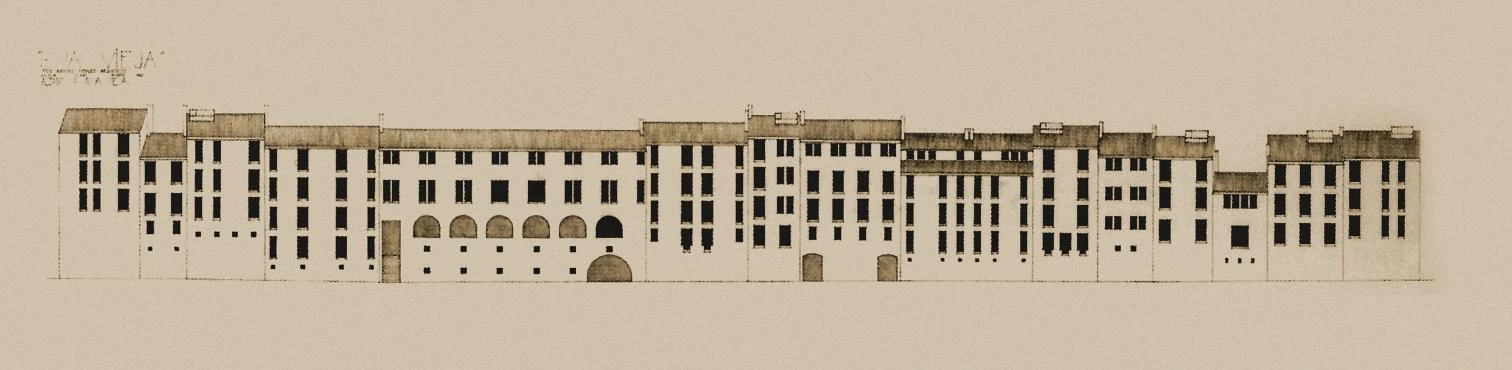

Moneo’s relationship with the Barcelona urban planner Manuel de Solà-Morales was also key to his assimilation of Italian discourses on the city. Their collaboration began with a proposal for redeveloping the old quarter of Zaragoza (1969–70). A strong typological approach to the project can be seen in the Actur de Lacua residential development in Vitoria (1976–80), also in conjunction with Solà-Morales, besides the Urumea apartment building in San Sebastián (1969–73). The influence of the Italian architects is evident in his entry to the competition for the College of Stock Exchange Agents (1973) or his proposal for renovating the Center of Eibar (1973–74).

Nevertheless, it was in his major commissions of that period, such as for Bankinter (1973–77) in Madrid and the City Hall of Logroño (1973–81) that his new approach to design reached its maximum potential. These are buildings where the compositional freedom of parts allows incorporating fragments of previously tested architectures, the requirements of the program, and the particularities of the context, but all this without loss in the integrity of the building as a formally defined entity in the city fabric.

The International Scene

In 1976–67, Moneo took a sabbatical leave from the Barcelona school and accepted Eisenman’s invitation to the Institute for Architecture and Urban Studies in New York. During this first stint in the United States, Moneo was invited by Hejduk to be a visiting professor at Cooper Union, and the next year he was invited to Princeton. The contact with these colleagues – and also with Gandelsonas, Silvetti, Vidler, and European architects like Stirling and Koolhaas – opened new intellectual perspectives for him.

At the close of the 1970s, architectural debates on the East Coast were characterized by an emphasis on theory and graphic speculation, to the point that actual building work was slighted. Moneo always rejected the idea of theory being independent of construction, claiming it possible to have a theoretical position derived from building experience. Nevertheless these first contacts with the American scene were an opening to a broader architectural discussion that freed him of many of the biases of the more closed architectural community from which he had come. In 1980 he left Barcelona to head the Composition Chair in Madrid, and thereafter his axis was Madrid-New York.

La apertura internacional de Moneo no ha mermado su compromiso con el contexto, presente, entre otras, en el plan para Logroño, la ampliación del Banco de España, el Museo de Estocolmo o el Messepalast de Viena.

Starting in the late 1970s, reflections on typology and urban morphology, still present in his plan for the Rúa Vieja in Logroño (1979–82), coincided with more controversial projects, such as the enlargement of the Bank of Spain headquarters in Madrid (1978–80) or the proposal for the Cannaregio in Venice (1978–9), Moneo’s first international hit.

During those years Moneo’s architecture took on a greater degree of formal and linguistic complexity, evident in the Previsión Española building in Seville (1982–7) or the Bank of Spain offices in Jaén (1980–8). But it was most patent in the National Museum of Roman Art in Mérida (1980–6). The building’s structure, defined by an axonometry inspired in Choisy drawings, condenses scales, urban layers, and construction systems, as if the building could be absorbed in a single but complex formal entity.

The American Experience

The first transatlantic contacts were rewarding for Moneo. In 1985 he was appointed chairman of Harvard’s Department of Architecture, for which he lived in Cambridge (Massachusetts) for five years. His arrival there raised expectations of a return of the importance of the built work and a reestablishment of the link between theory and construction, as against mere graphic speculation, then so dominant in American universities. This was the main theme of his inaugural speech at Harvard, ‘The Solitude of Buildings’.

His U.S. experience did not only bring back for him an awareness of the relationship between architectural thinking and actual building, a legacy of his training in Madrid. It also brought a new way of regarding the city and scale. From the mid-1980s on, his buildings were more liberated from the direct dictates of urban morphological consistency. Some larger projects became major infrastructures, such as Atocha (1984–92), urban containers of enormous scale, such as L’Illa Diagonal in Barcelona (1987–94, again with Solà-Morales), or geographic accidents which were more than urban, such as the Kursaal of San Sebastián (1990–99). Other projects were outright negations of immediate urban context, such as his entry for the Progetto Bicocca in Milan (1985), or more subtly the Miró Foundation in Palma de Mallorca (1987–92) and the Auditorium of Barcelona (1987–99). It was also during the Harvard years that he began to project his building career outside Spain by participating in international competitions with certain success, although the first commissions abroad came in the next decade.

A Global Practice

With commissions piling up in Spain, in 1990 Moneo ended his stint as architecture chairman at Harvard and returned to Madrid. So began his years of world acclaim, with top honors following one another and including the Pritzker in 1996. He also began to take on major international commissions and became a figure in the emerging global ‘star system’. The more he became part of this world scene, however, the more he channeled his discourse toward the importance of construction in design, and his major reflections of that time, such as the conference ‘The Whisper of Place’, were assertions of this stand.

For Moneo, place does not necessarily dictate the architecture to be built, but that it must be interpreted, even confronted, which is why he often prefers to use terms like ‘appropriate’ for ‘contextual’ and ‘site’ for‘place’. Each work is imbued with the spirit of site conditions. The subtle elevation, seen from the city, of the Museums of Modern Art and Architecture of Stockholm (1991–8), the abstract altarpiece facing the cathedral in the enlargement of Murcia’s City Hall (1991–8), or the compactness of the Audrey Jones Beck Building of the Museum of Fine Arts (1992-2000) in Houston’s disperse grid are materializations of such reflections, as are the Cathedral of Our Lady of the Angels (1996-2002), the enlargement of the Prado (1998-2007), and the more recent Laboratory Building at Columbia (2005–10), which brought this global practice into the 21st century.