Exile has been integral to a good part of the social landscape of the 20th century. And given the political dimension of their work, architects have not been exempt from this. Certainly not the subjects of a retrospective curated by Martín Domínguez Ruz and Pablo Rabasco at Museo ICO, Carlos Arniches and Martín Domínguez, whose lives were changed by the outbreak of the Spanish Civil War.

Martín Domínguez (San Sebastián, 1897) was an important representative of exiled Spain. Early in 1937 he moved to Cuba, and in 1960 to the United States, his expatriate status and fidelity to republican and liberal ideas in tow (he had been close to the Republican Left, the political party founded by Manuel Azaña). Carlos Arniches (Madrid, 1895) suffered a no less painful domestic exile and was part of the discredited ‘Ellos’ caste, excluded from the ‘Nosotros’ of the winners, as his friend Fernando Chueca Goitia put it in Materia de recurerdos.

It was precisely Fernando Chueca who wrote an obituary of Arniches in the Madrid daily ABC when he died in 1958. When Martín Domínguez passed away in New York in 1970, the secular funeral held at Cornell University – in whose College of Architecture, Art and Planning he had taught – included eulogies by other Spaniards in exile, such as Félix Candela and Francisco García Lorca, besides the influential architectural critic Colin Rowe and the school dean, Kelly.

The professional paths of Arniches and Domínquez had begun in the Madrid of the happy 1920s. They graduated from the Madrid School of Architecture in 1923 and 1924, respectively. During those years they connected with the more conspicuous members of the Generation of 27. Martín Domínguez linked up especially with the group headed by the poets Federico García Lorca and Emilio Prados (having lived at close range with them, as a student, at the Residencia de Estudiantes), and Carlos Arniches with the team of the humorists Edgar Neville (for whom both designed his Madrid home, an attic overlooking Retiro Park, from which Le Corbusier stepped out all stunned by the visit arranged by the architects in May 1928), Antoniorrobles, Tono, and López Rubio, with whom he stayed in touch through his father, the famous writer of one-act comedies and dramas of the same name.

But the two figures who were leading references for Arniches and Domínguez were Secundino Zuazo and José Moreno Villa. To Zuazo they were tied professionally, as collaborators in his studio. And with him they got to sign some projects, such as the Zahara café and the Nuevos Ministerios station for railway connections. They also co-authored a project with another senior, Amós Salvador. Moreno Villa, in contrast, was their intellectual mentor through lessons he gave as an architectural critic delivering lectures and writing articles in the magazine Arquitectura and the Madrid daily El Sol, the same newspaper for which Arniches and Domínguez wrote a weekly architectural page from 1926 to 1928, under the title that now names the exhibition about them.

In Madrid of the Republic

Their work during those years, up to July 1936, defined the more refined and progressive image of republican Madrid, as Oriol Bohigas stated in his indispensable book Arquitectura española de la Segunda República. Here it was important that Arniches and Domínguez were closely tied to the modernizing project of the Institución Libre de Enseñanza and its satellite centers. In fact, in 1927 Carlos Arniches was named architect of the Junta para Ampliación de Estudios e Investigaciones Científicas, a post he held until civil war broke out.

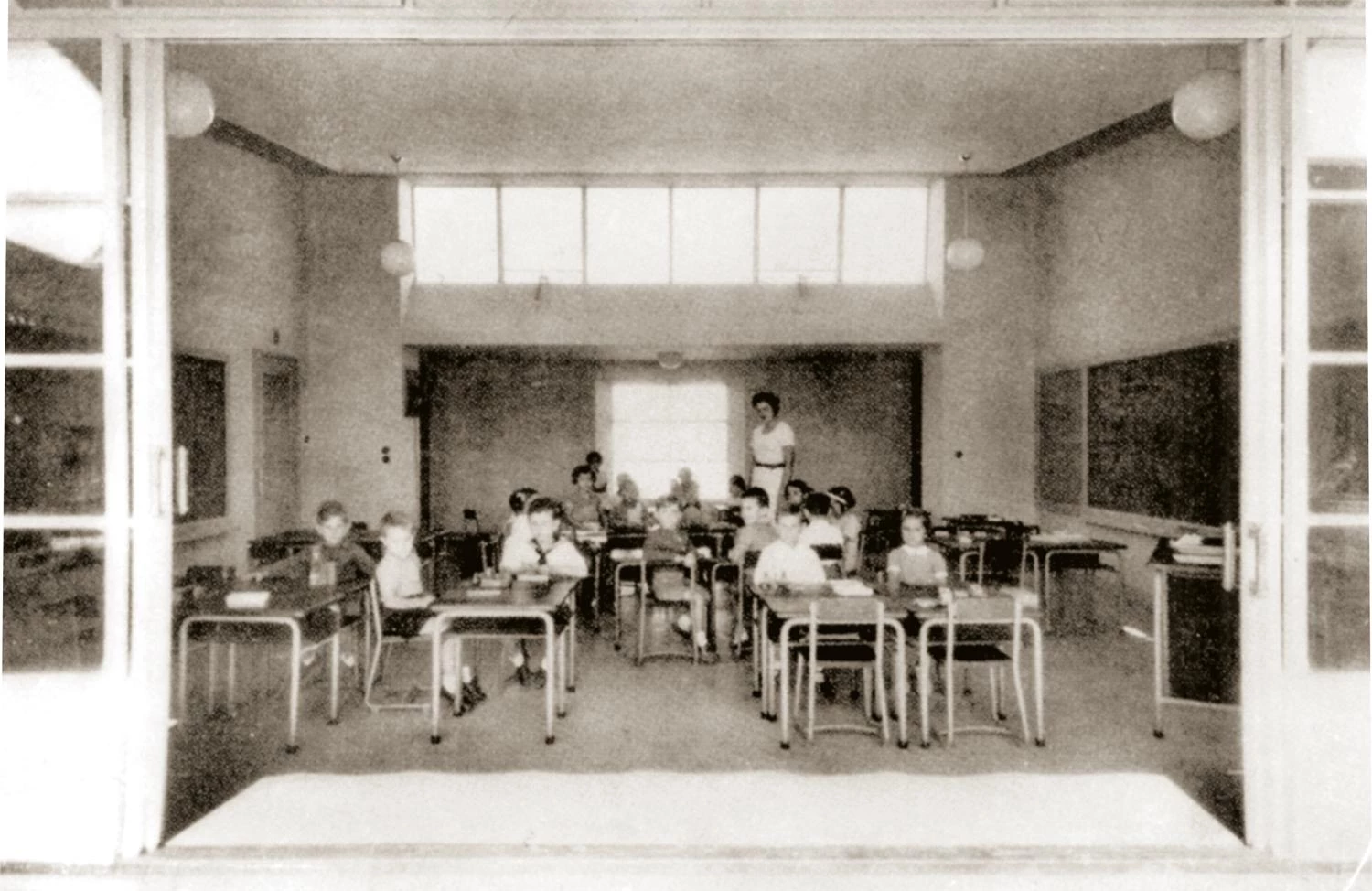

Together Arniches and Domínguez built, starting in 1930, the two new pavilions of the Instituto-Escuela on the Colina de los Chopos in Madrid. The Instituto-Escuela, founded in 1918, was conceived as an experimental school and also as a training center for teachers, the pedagogical initiatives of which would hopefully be applied to public education nationwide, once tested. What stood out in the secondary education building was the double construction of the classroom building, “which rests on columns of reinforced concrete, colored light blue and covering a part of the courtyard used for outdoor classes in summer, and as a recreation place on days of bad weather. The roofs are flat, so they form roof terraces […] good for sunbathing and gymnastic exercises,” as the project description says. As for the admirable nursery school, its avant-garde architecture was a paradigmatic example among the new educational constructions, where the innovative architectural conception of the classrooms promoted the creation of spaces that were more flexible and more engaged with the exterior. Moreover, the canopies, a fruit of the architects’ collaboration with the engineer Eduardo Torroja, had a definitive bearing on the sequence of classrooms and food gardens of the new pavilion.

Arniches and Domínguez also designed a building to house the lecture hall, library, and classrooms of the Residencia de Estudiantes, a center inspired in the English model of colleges and conductive to a spirit of unity and interaction between science and culture, whose program of public events was so successful that soon it was necessary to think of an extension, beginning with a modern auditorium. Inaugurated in 1933 and converted after the Civil War, by Miguel Fisac, into the Church of the Holy Spirit, its various functions were materialized around a cloistral courtyard, existing to this day, featuring large classical arcades built in unfaced brick with an austere compositional abstraction of early 20th-century stock.

Finally there was the new dormitory pavilion of the Residencia de Señoritas, a university center created by the JAE as an incentive to include women in higher education, which operated from 1915 to 1936 under the direction of María de Maeztu. It was carried out by Carlos Arniches, solo, in 1932, and his architecture is an expression of the rationalism of restraint and sobriety while addressing its urban location on a corner of Madrid’s gridded expansion. Refined furniture designs completed the architectural project.

Both Arniches and Domínguez were also architects of the Patronato Nacional de Turismo, for which they executed almost a dozen roadside hotels, injecting into them a bold interest in tradition from the angle of fully modern standards of comfort and functionality. Manuel Azaña’s book Vigil in Benicarló takes place in one of them.

Surely their most disseminated and significant work is the Hipódromo de la Zarzuela. Resulting from a competition of preliminary designs, organized by the Gabinete Técnico de Accesos y Extrarradio de Madrid (since the location of the Royal Hippodrome at the end of the Paseo de la Castellana was an obstacle to the city’s northward development plans established by the Zuazo-Jansen plan), the proposal drawn up by Carlos Arniches and Martín Domínguez with the engineer Eduardo Torroja was chosen over the other eight entries by the jury composed of José Fonseca, Luis Goyeneche, José de Lorite, Manuel Sánchez Arcas, and Alberto Laffón.

In the story of the Zarzuela Racetrack, there is a dramatic moment during the Spanish Civil War. Bombs fell on the building when it was at an advanced stage of construction. The building suffered major damage thanks to its location right on the war front during the siege of the capital by Franco’s troops. It would not be inaugurated until 1941, without the architects, by this time in exile. Today it is unanimously considered a masterwork of Spanish architecture of the first half of the 20th century. Nevertheless, as far as the racetrack and its historiographic assessment is concerned, there has always been a bias, that which thinks that architecture is damaging to engineering. But the two languages support and reinforce each other. The vernacular wisdom of its implantation in the place and the graveness of the refined arcades strike a contrast with the lightness of the hyperboloids of the lamellar reinforced concrete roofs of the canopies of three grandstands. In sum, the Zarzuela Racetrack is a work of synthesis.

Postwar and Exile

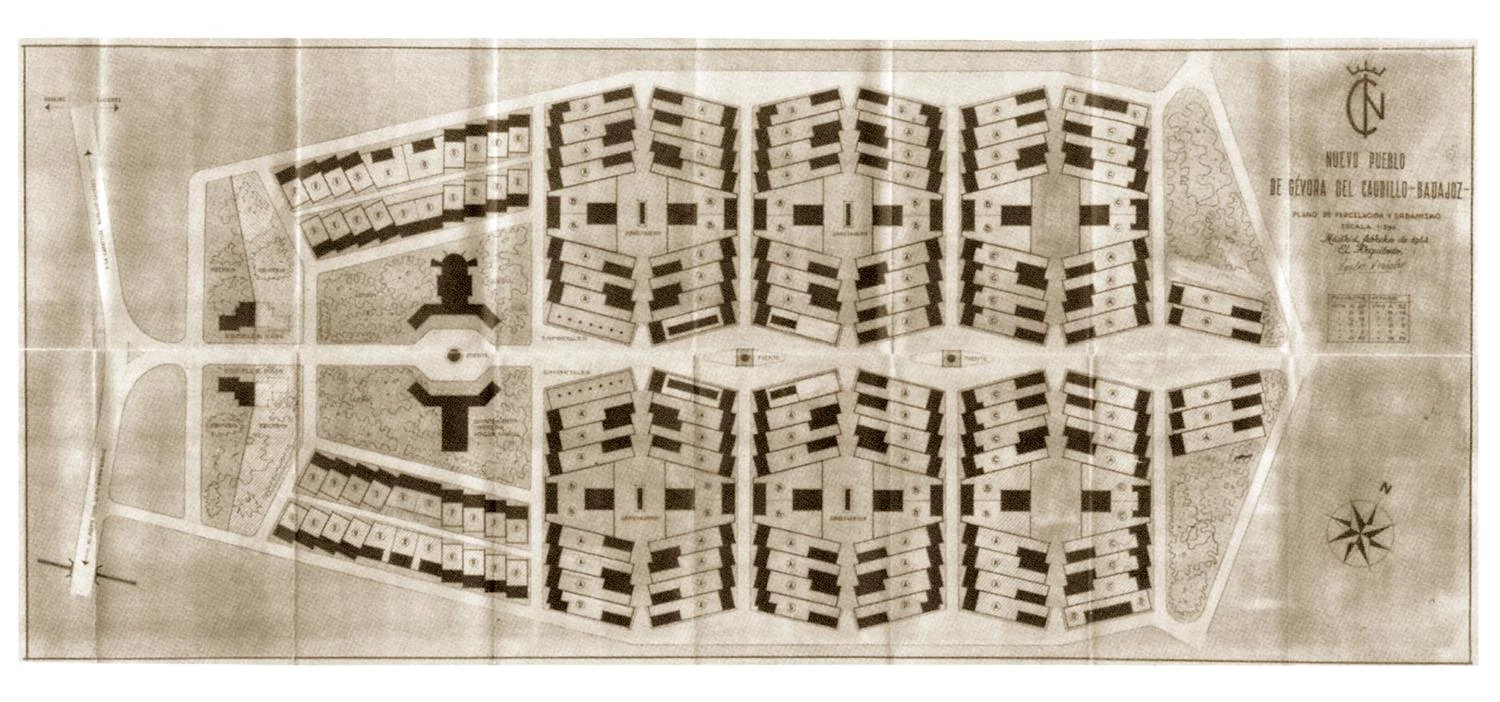

After the Civil War, Carlos Arniches initiated a discreet inner exile surrounded by friends like Fernando Chueca Goitia, Alfonso Buñuel, José Bello, and Domingo Ortega, and also the very young Juan Benet, among others. After complying with the sanctions imposed by the new powers-that-be, he carried out two new towns for the Institito Nacional de Colonización: Algallarín in Córdoba province, and Gévora in Badajoz. Also a handful of one-family houses, among them one for Concha and Isabel García Lorca when they returned from North American exile in 1951: a beautiful and simple countryhouse in Meco, a municipality of Metropolitan Madrid, where popular language was used to make an avant-garde work. We can have a look at it in Antonio Artero’s film Yo creo que.

After complying with sanctions imposed by the new powers-that-be, Carlos Arniches designed the new towns of Génora and Algallín with his refined style based on a balance between modern and vernacular.

For his part, Martín Domínguez in the Cuba of Fulgencio Batista executed a significant and abundant oeuvre identified with the Modern Movement’s new postulates, those formulated in the wake of World War II. This included the multipurpose Miralda and Radiocentro buildings, carried out with Emilio del Junco and Miguel Gastón, as well as the FOCSA building, done with Ernesto Gómez Sampera, also in Havana. Along with these architectures of cosmopolitan views, he produced a large body of work in the field of social housing. With Fidel Castro’s coming to power he went into a second exile, settling for good in the United States, where he taught at Cornell University and built the Lennox House, his final work.

Between his departure from Spain and his settling for good in the USA, MArtín Domínguez lived in Cuba, where he built multipurpose buildings in a language of postwar modernity at its most cosmopolitan.

The architecture of Arniches and Domínguez chose the road of reconciliation, as so well stated by Adolf Behne – whose ideas had been disseminated within Spain by Moreno Villa – in his book Der moderne Zweckbau: “It seems to us that every construction contains something of a compromise: between finality and form, between the individual and society, between economics and politics, between dynamics and statics, between eloquence and uniformity, between body and space, and that style is none other than the concrete version of that compromise.” From some equivalent coordinates, Carlos Arniches and Martín Domínguez liked using the expression ‘reasonable architecture.’

Salvador Guerrero teaches architectural history at ETSAM.