Major questions

Building for the Elderly

GRND82, 85 Sheltered Housing Units for Senior, Barcelona (Spain)

“For whom are houses built? For man, without a doubt.” The question posed by Le Corbusier remains relevant in our aging societies, yet many essential aspects of human life – old age, disease, physical decline – continue to be assigned to spaces which are separated from our normal everyday experience.

Architecture is subject to a strong orthodoxy in terms of where and how to place certain functions. Contemporary architecture accepts the ideal of multipurpose structures, as it were, yet it never occurs to an urban planner to mix the usual spaces with spaces associated with old age or degradation. Often located on the outskirts of cities, buildings serving old age, decadence, and illness lie beyond the reach of our corporal awareness.

It is clear that architecture simply gives material form to the mental structures of consumerist society. The idea of old age has no place in a society that only has praise for virtues like youth, mobility, or success. Hence the scarcity of alternatives: either expel the elderly and disabled to absolute non-places, or assign them topographies which are well defined but camouflaged, aesthetically questionable, and introverted. Nevertheless, though lacking visibility in a society afflicted with iconic bulimia, we can cite cases of dwellings for senior citizens that, addressing their problems with exquisite attention, uphold the dignity of life’s twilight.

Far from hiding old age, the most innovative designs treat it naturally and bring it out.

Innovating for Old Age

The aging of populations is a world reality. In Spain now, 18.4% of the population is older than 65, and 93.6% of this group prefers to stay in their own homes as long as possible. This is attributable to three key factors. One has to do with ownership, as much as 89.3% of Spaniards over 65 boasting a dwelling which is fully amortized property. The second factor is medicosocial in nature, having to do with average life expectancy (barring sudden disability) and cultural literacy being on the rise. The third is economic, the cost of transferring from one’s own home to assisted living or something similar amounting, depending on income level, to the equivalent of the expense incurred when one moves from a low-cost to a luxury hotel.

MVRDV, WoZoCo Apartments, Amsterdam (Netherlands)

Peter Zumthor, Home for Senior Citizens in Masans (Switzerland)

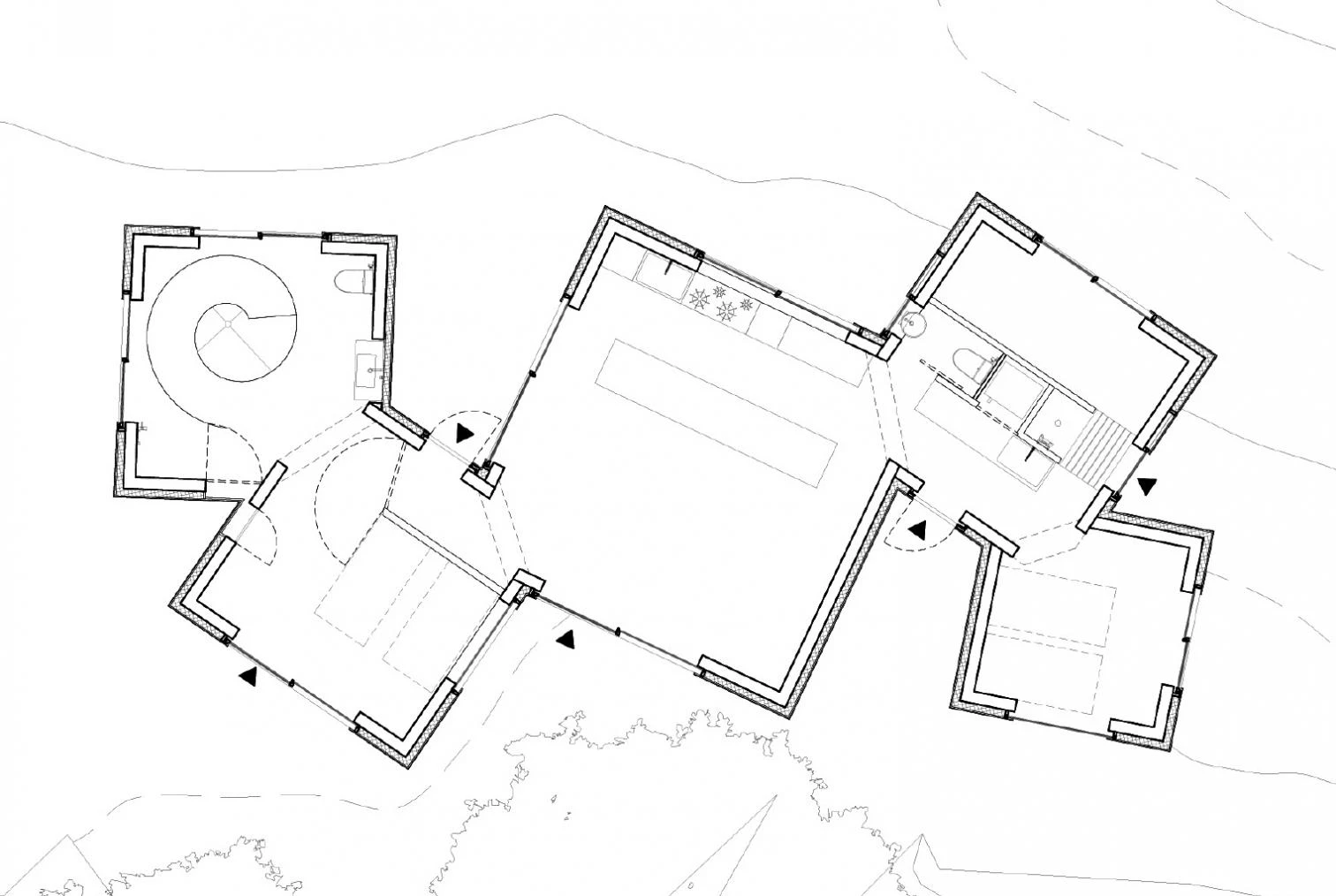

Zumthor’s home for seniors in Masans was the precursor of several residences of amiable scale, integrated in the context through their materials, such as those by Issei Suma, Óscar Ares and Dieter Wisshounig.

It has been demonstrated that continuing to live in one’s own home is a very good option, enabling the elderly to keep active and guaranteeing quality of life. But we have to accept that many elders come to need external intensive care as the end nears, and that adapting their longtime homes to their new circumstances involves costs which are impossible or difficult to shoulder. These homes then become virtual prisons for elderly people.

In Spain’s social model, traditionally, dependence-related problems were managed in either of two ways: either families brought their elders into their households, or the elders were entrusted to homes for the aged. The challenge is great and the social model is changing, and many efforts are being made in areas beyond institutionalized caregiving, such as the design of innovative, alternative dwellings for senior citizens that address varying degrees of fragility and dependence.

Peter Zumthor, Home for Senior Citizens in Masans (Switzerland)

We can mention a number of innovative types and arrange them from lowest to highest degree of institutionalization: single senior dwellings, shared senior dwellings, intergenerational arrangements, supervised dwellings, assisted living, institutional residences, and, finally, geriatric institutions. The objective of these new models is to stretch the time that older people are autonomous, prolong their stay in independent homes as long as possible, and parallel to this, replace institutional caregiving with radically new nursing models, with much smaller units for living together and attention centered on individual persons.

For a Decent Dwelling

The projects featured in this issue try to illustrate the current state of collective living for senior citizens, not only in Spain but also in other countries where the theme is being debated on and subjected to a rethinking. All of them take from two unavoidable references, separated by two decades: the home for senior citizens built in 1993 by Peter Zumthor in the Swiss locality of Masans, and one in Alcácer do Sal (Portugal) by Aires Mateus in 2013 (see Arquitectura Viva 41 and 136). These represent two ways of looking at and creating architecture for old people which are complementary but in some ways opposed.

Oscar Ares, Home for Senior Citizens in Aldeamayor

CAn + Met Architects, Shobara (Japan)

Zumthor’s ultimate desire was that the inhabitants of his center’s twenty-one apartments for older people would feel at home, and with this in mind he set the bases for a painstaking design, an architecture which was respectful towards the user and towards the environment, to an extreme. What he did was create a rural atmosphere in a suburban environment, use local materials as an expression of domesticity, and break up the building’s scale by forming complementary spaces: private ones with views of the surrounding landscape, and semiprivate and public ones where one goes to see and be seen.

Dietger Wissounig Architekten, Home for Senior Citizens in Graz (Austria)

Similar strategies are evident in the residence for elders in Aldeamayor (Valladolid) by Óscar Ares, where courtyards are connectors facilitating contact with nature and among the users, or in the dwelling with courtyards in Barking (London) by Patel Taylor, where elements of a traditional housing development are distilled and translated to an intimate and domestic scale, or in the caregiving residence-home in Andritz (Austria) by Diener Wissounig, where the scale is broken through materials and the formation of four wings facing semipublic courts.

Issei Suma, Nursing Care in Ike (Japan)

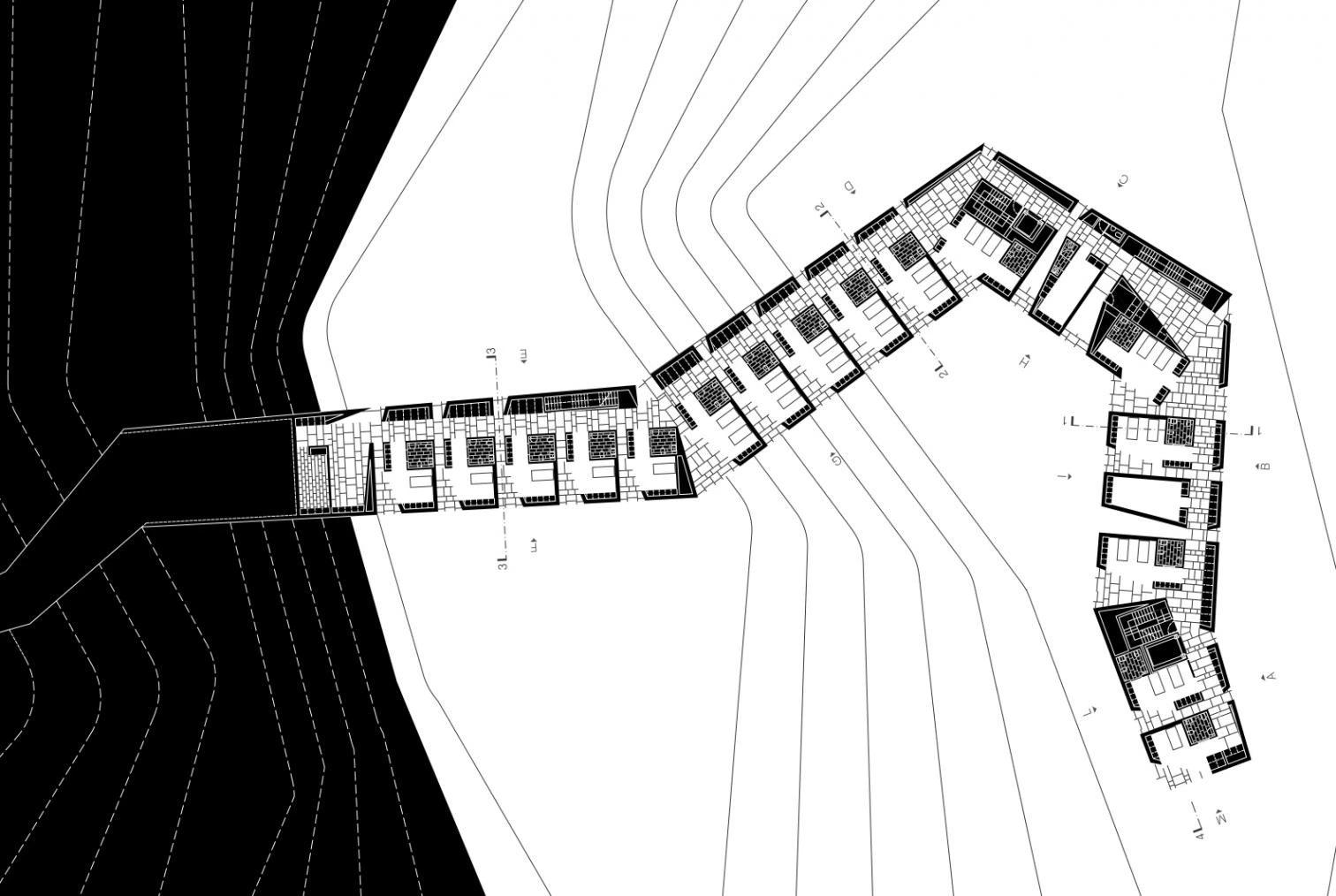

Aires Mateus, Residence for Elderly People, Alcácer do Sal (Portugal)

With a scale infinitely smaller but similar in some of its approaches to the foregoing, we find the delicious retirement dwelling of the Jikka community in Shizuoka (Japan), by Issei Suma, which through a near-ethereal materiality succeeds in sealing a very serious commitment to the disabled, putting the users and their engagement with the surroundings at the very core of the design’s conception.

Aires Mateus, Residence for Elderly People, Alcácer do Sal (Portugal)

As for the Aires Mateus project in Alcácer do Sal, it goes a step further in redefining an architectural typology, creating a geriatric center halfway between a hotel and a hospital, in an endeavor to understand, reinterpret, and respond to elderly people’s need for both social life and solitude. Efforts made to establish cross views, encourage encounters, and form routes that turn lack of mobility into experiential opportunities, but also to ensure the dignity of privacy at all costs, are some of the strategies used by an architectural team known for its exquisite minimalism of the kind that is able to transform something complex into something simple.

Aires Mateus, Residence for Elderly People, Alcácer do Sal (Portugal)

They are features we find in the circulation routes and scale-breaking of the social complex in Alcabideche (Lisbon), by Guedes and Cruz, and especially in the richness of space and the search for diagonal visual relationships in the collective senior housing with services, by Bonell i Gil and Peris+Toral, in Barcelona. In this project the architects redefine the living unit, creating a central core of services – quite an unusual feature in this typology – that makes the space perceivable as something unlimited: an innovation that in a brilliant and complex way addresses the needs of the user who spends a lot of time at home.

Aires Mateus, Home for Senior Citizens in Alcabideche

The firm Aires Mateus’s project in Alcácer do Sal redefines the traditional geriatric center model through a balance between private rooms and communal spaces: a scheme used by Guedes Cruz and Sergison Bates.

Take the caregiving housing development in Wingene (Belgium) by Sergison Bates architects, which seems to appropriate the postulates of caregiving architecture set by Zumthor, but is no less noteworthy in its effort to break scales, form paths, and encourage socializing among users in a sophisticated way.

Sergison Bates, Residence, Wingene (Belgium)

Avant-Garde and Rearguard

Knowing these precedents, if we try to answer the question of Le Corbusier with which this article began, a parallel question arises. If what people want is to stay in their own homes, why don’t we design dwellings that are good for all ages and conditions? Is it the current notion of disability that keeps us from doing this? There are two architectural stands with respect to the matter. The riskier one is what leads to revolutionary change, radical (avant-garde) typological reinvention; the other one, more optimistic, pursues a more evolutionary model based on the transformation of the type, and is more modest, but not for that reason less efficient (rearguard).

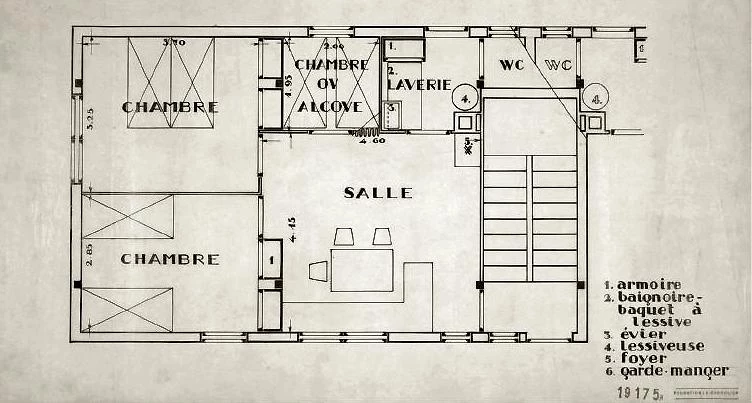

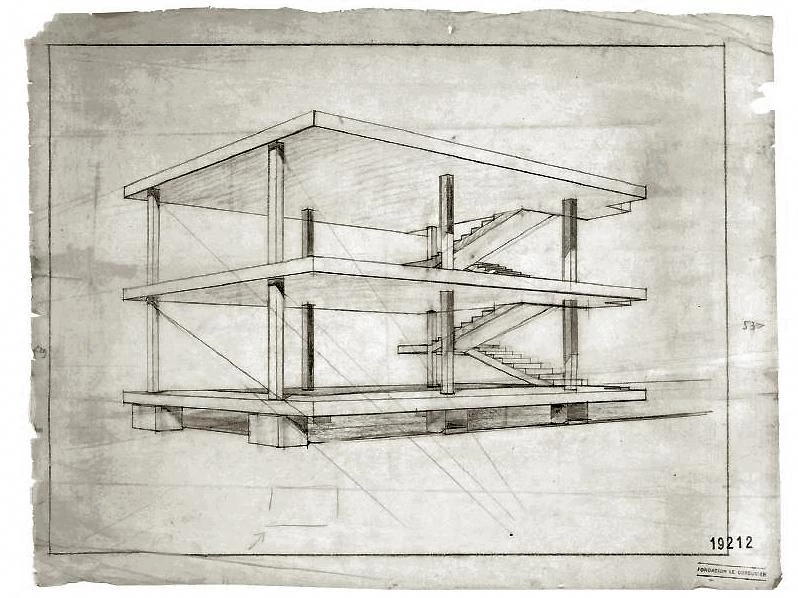

Le Corbusier, Maison Dom-ino (1914)

Le Corbusier, Maison Dom-ino (1914)

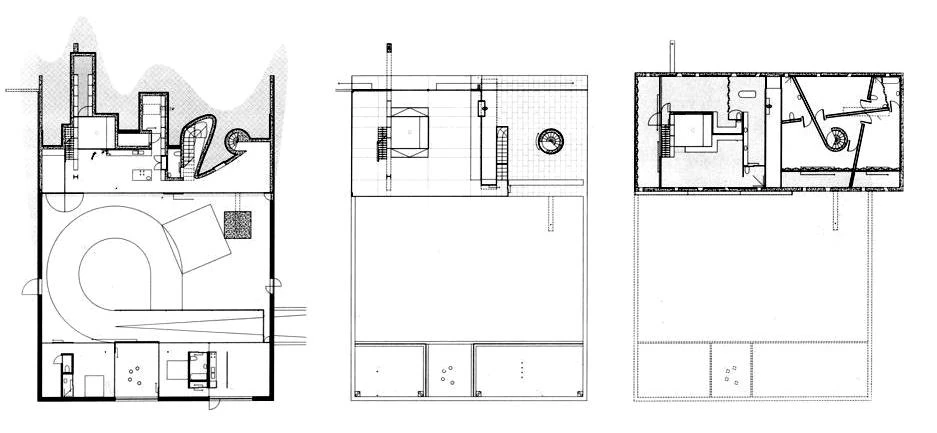

The Venice Biennale of 2014 – curated by Rem Koolhaas and titled ‘Fundamentals’ – proposed a return to basic inventions of modernity, those considered references and sources of inspiration. The Maison Dom-ino that Le Corbusier designed in 1914 was built for the first time, by the Architectural Association of London. This prototype, never materialized as such, became one of the most iconic modern projects of the 20th century. Later, in 1931, without knowing it and through his promenade architecturale, Le Corbusier created in Villa Savoye the first auteur-architecture dwelling in contemporary history that was highly accessible internally, with its deployment of continuous ramps leading to all floor levels, providing a range of experiences and contributing to defining the house’s spatial features.

Le Corbusier, Villa Savoye, France (1929)

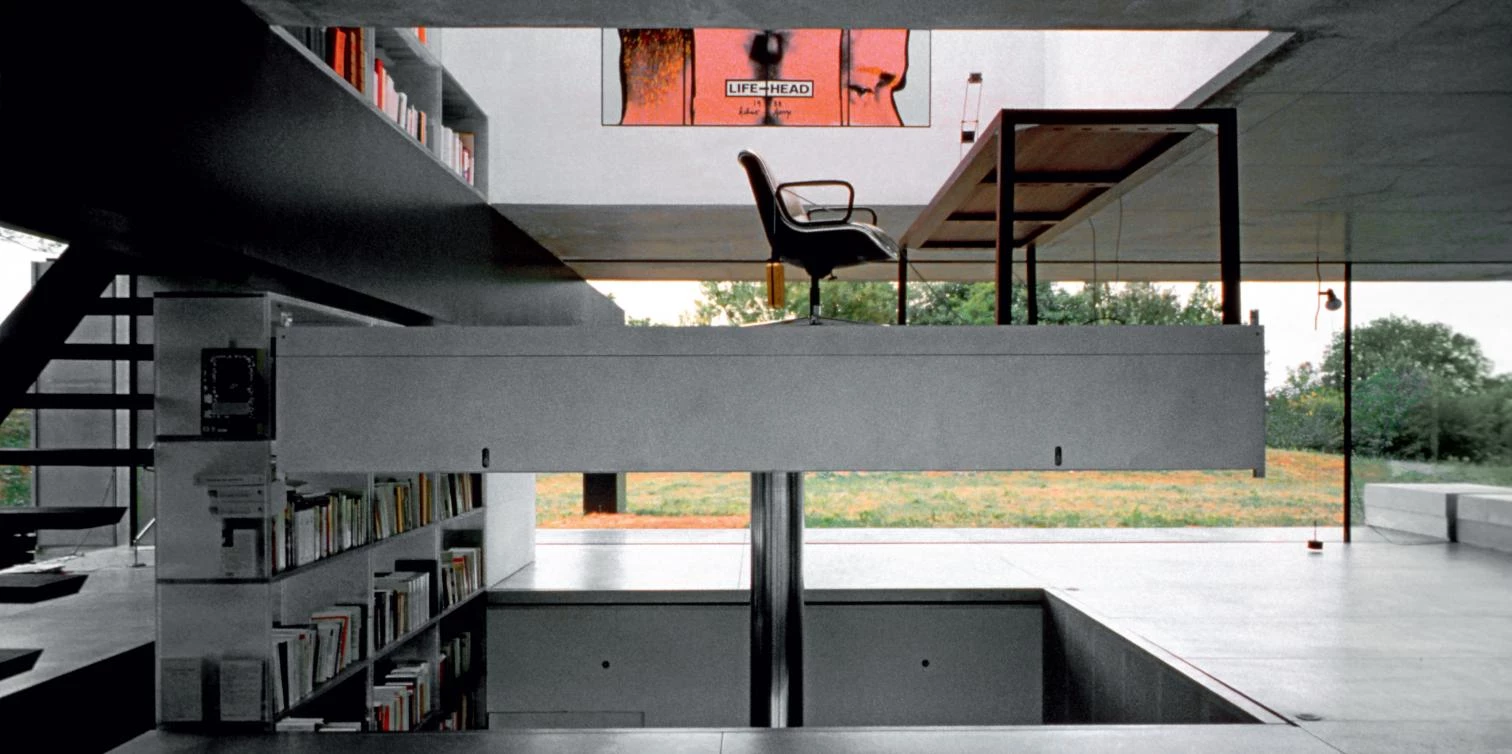

As in the Le Corbusier case, OMA, without meaning to, created in its 1992 design for two libraries in Jussieu (Paris) a typology that was totally accesible internally. The floors are not stacked, but manipulated, bent here and there to interconnect and form a single circulation route resembling an indoor boulevard snaking through an entire building. This had its premeditated version in the Bordeaux house of 1999, where Koolhaas took on the special commission of planning a private house for a quadriplegic client. By means of an ascending and descending platform situated at the center of the building, Koolhoos created a mobile room which, depending on where it is, completes the layout of the house on each of the three floors. Adversity is inspiration for a home of total mobility which has a sure place among architectural icons of the 20th century.

Rem Koolhaas, Maison a Bordeaux, France (1999)

Beyond hyperspecific technical solutions, we can find utopias of universal accessibility in works as radical and well known as Le Corbusier’s Villa Savoye and Rem Koolhaas’s House in Bordeaux.

Rem Koolhaas, Maison a Bordeaux, France (1999)

Taking the examples featured in the current issue, excellent works of the rearguard, and comparing them with the avant-garde attitude of Le Corbusier and Rem Koolhaas, I would like to end this article lamenting not having found a 21st-century built example of architecture for elderly people that is truly radical, that takes risks, and that proves, from the avant-garde, that there are other ways to ‘design for man.’ Like architects, we ought to be able to create promenades architecturales and ‘vertical boulevards,’ not just plain corridors and ramps with 6% slopes. Or ‘bathrooms,’ not just wet rooms. Or ‘room-lounges,’ not just dining rooms. In sum, homes for all, not just adapted.

Paz Martín, an architect, is the curator of the exhibition ‘Envejezando. Diseño para todos: Arquitectura y Tercera Edad,’ which opens at the COAM on 13 June.