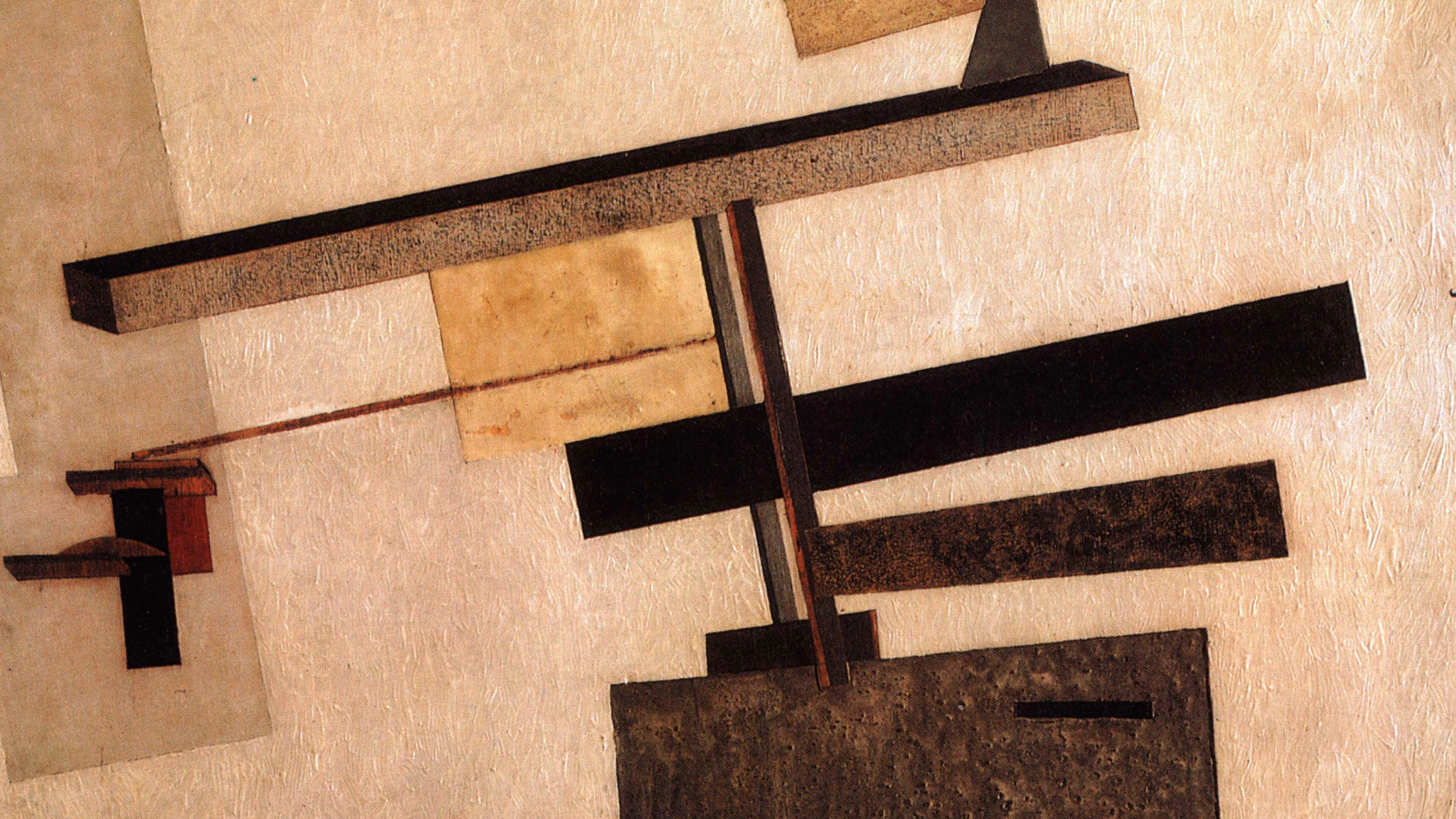

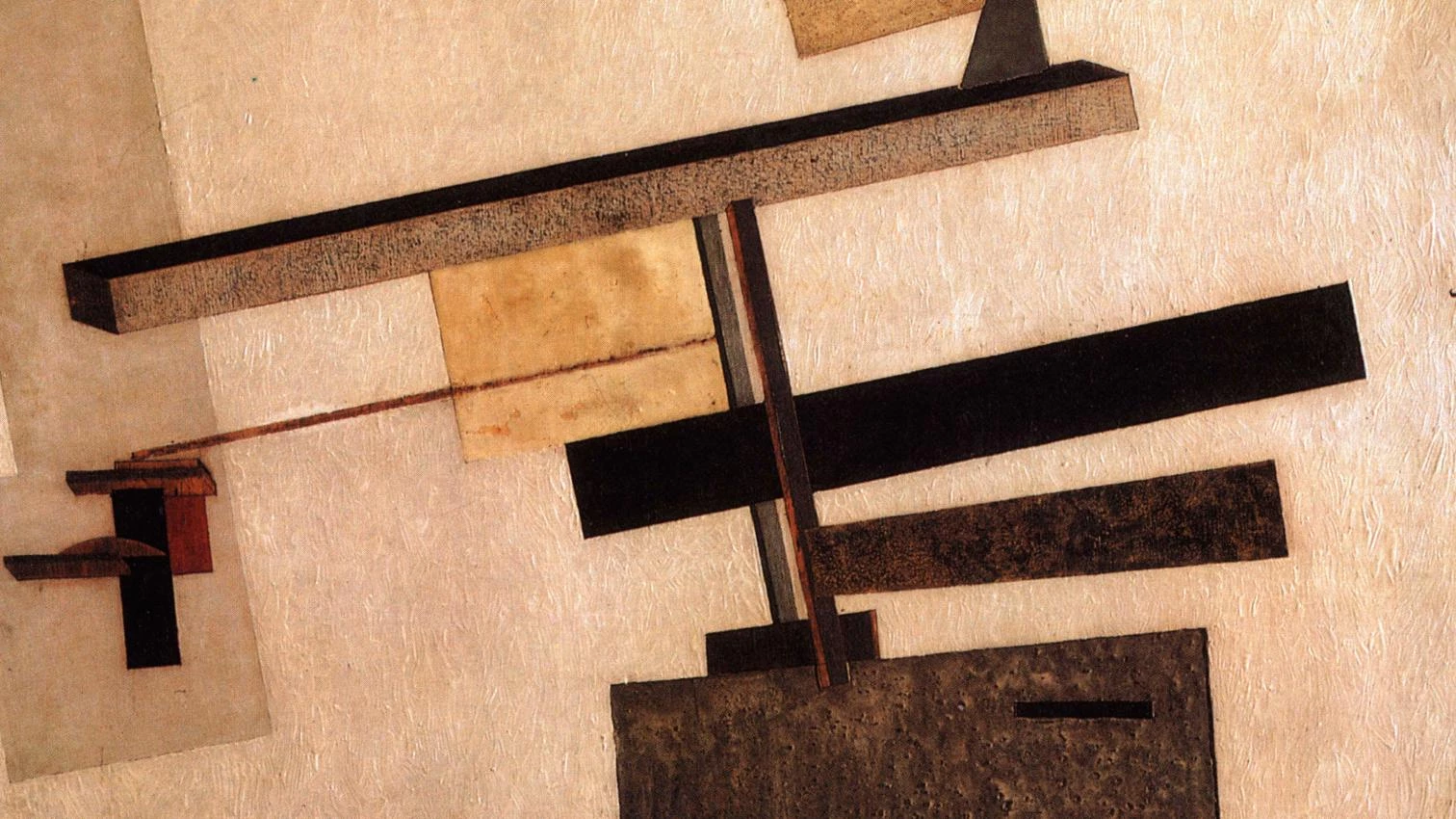

El Lissitzky, Proun 2c, near 1920

“Neither the old nor the new: the necessary.” Thus did Tatlin define in 1920 the attitude of an avant-garde determined to construct a useful art. Both his culture of materials and his emphasis on production were in line with that will to merge art with life, in the whirlwind of a process of political, economic, social and cultural change that had dragged people, upset ideas and erased the limits between activities. “The necessary” was a point of support and an axis for action; a certitude and a program; an aesthetic guide and an ethic credo.

As much as if not more than the Monument to the Third International exhibited that year - and which instantaneously became the privileged icon of Constructivism - it is the Letatlin, the flying artifact he built between 1929 and 1932, that best expresses that ethics of the necessary. A piece of functional art and alternative technology, futuristic and archaic at the same time, Tatlin’s device is a flying bicycle for the people, magically linking engineering to organic reason at the service of the old myth of human flight.

The dream of freedom and the utopia of nature, both part and parcel o f a project for social emancipation, constitute the necessary nucleus of a useful and perfect sculpture. Built in ash, lime and willow wood, with ropes and cloth of silk, and with cork, hide and whalebone, this living machine is more than an Icarus or aereal manifesto: Letatlin is the guardian angel of the Russian Avant-Garde. A fiercely human angel, as far from the gentle being of Rilke as from the somber wings of Klee’s, as evoked by Benjamin.

In this creature that is both mechanical and organic, celestial and earthly, exact and impossible, art blends with life, necessity with the project. No architecture was ever so accurate in its grouping of ideas with forms; so eloquent in its mythic and symbolic passion; so luminous and daring in its improbable adventure; so beautiful in its burnt catastrophe, wounded like a bird of wax melting into cinder and shade.

When the formal fatigue of a worn out century makes the pure images of the Russian avant-garde circulate in its dizzying carrousel, one cannot help feeling the slight and ominous threat of nausea on an empty stomach. The artistic diplomacy of glasnost, which is permitting an in-depth knowledge of a crucial epoch, is also providing material for a oceanic falsification: possibly never before have so many forms been diffused so meticulously boned of the ideas they originally were born from.

We can forget history, but as has frequently been said, history is sure not to forget us. The reuse of Constructivist images in numerous graphic fantasies and some highbrow Disneylands is frequently an empty and skeptic exercise that loots a rich patrimony of forms in the name of novelty demanded by our accelerated consumption. And few things are so removed from the ethic fiber and intellectual rigor of those who claimed for art the virtue of the necessary.