Francis Kéré, Workshop in Gando, Burkina Faso

We look to the East with fear, but the East also lies south. We have seen the chaos caused by Daesh in the Near East, but Jihadism has been destabilizing Sahel for a long time now; and we are shocked by the tragedy in Ukraine, but Russia is in Algeria, and with the Wagner Group in Mali or Burkina Faso, where the recent coups have forced the withdrawal of French troops, which tried to offer security through Operation Barkhane. The Alboran Sea is the frontier with the greatest economic and demographic gradient in the world, so perhaps the most important geostrategic challenge of the European Union isn’t so much its eastern frontier but its southern one: the African population grows at the same pace as climate change reduces the capacity to feed it, and the multiplication of conflicts increases migration flows that will soon be uncontrollable. The summit held in February in Brussels with the African Union concluded with good intentions on infrastructures, health and vaccines or development and education, but these cooperation efforts will unlikely reduce Chinese influence or limit immigration.

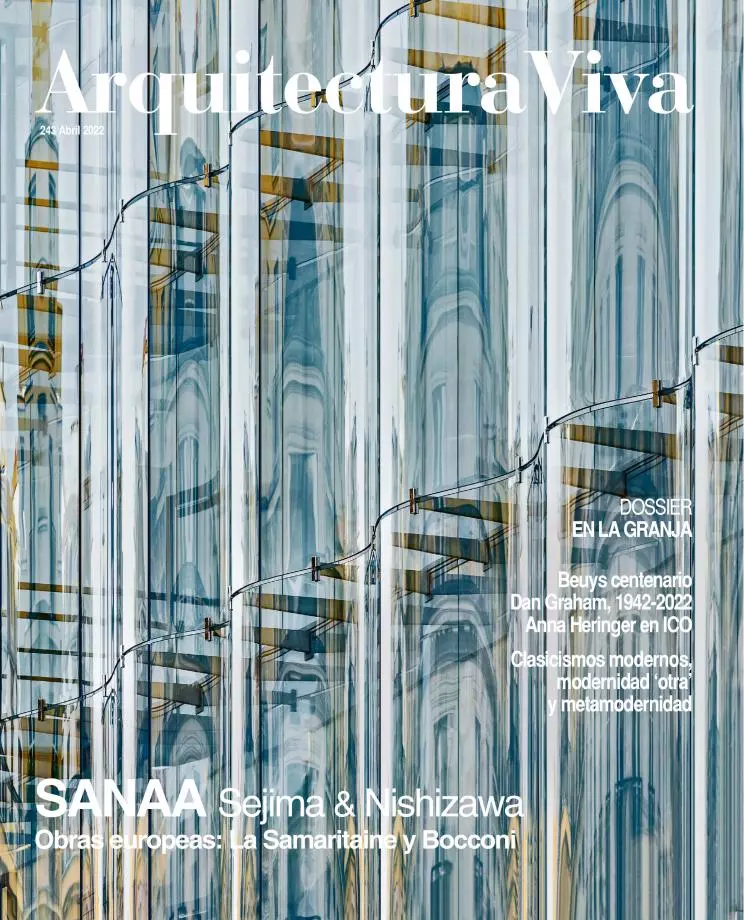

The Pritzker Prize has gone for the first time to an African architect, Francis Kéré, a Burkinese whose exemplary buildings combine technical and climate adequacy with social sensibility and aesthetic excellence, and the experience of visiting his works in Mali – the two countries that are the epicenter of the Sahel crisis today – is bittersweet. On one hand is the dazzling beauty of the landscapes and cities of the Inner Niger Delta, the Great Mosque of Djenné or the Venetian Mopti; the exact intelligence of vernacular construction, which reaches the sublime in the Dogon villages at the foot of the Bandiagara cliff; and the austere and colorist elegance of people dressed in with the aesthetic refinement of their textiles or wood carvings. But on the other is the constant feeling of insecurity in the territory, which episodically surfaces in killings or kidnappings; the difficulties in fulfilling daily needs, from water to food, not to mention education or health; and the multiplication of violence, which becomes evident with the proliferation of fire arms in the capitals of the two countries, Bamako and Ouagadougou.

In Mali there was a military coup in 2020, and the sanctions dictated by the ECOWAS against the government of Colonel Assimi Goita were unwelcomed by those who saw French influence in that organization, and in fact the coup of 2022 in Burkina Faso that ousted president Kaboré has been justified by his support of the sactions, driving lieutenant colonel Paul-Henri Sandaogo Damiba to power with popular demonstrations where Russian flags were waved. The coups in Sahel are also rooted in the frustration with failed anti-terrorist struggle, and it is not easy to ask for parliamentary democracies in such situation of insecurity. Kéré designed the parliament of this country after the fall in 2014 of dictator Blaise Compaoré, but now it is clear that he will finish the Benin one first, planned six years later. After all, as much his works in Sahel – in Mali and Burkina Faso, but also in Senegal, Kenya and of course Benin – demand political stability that is as important for that continent as it is four ours.

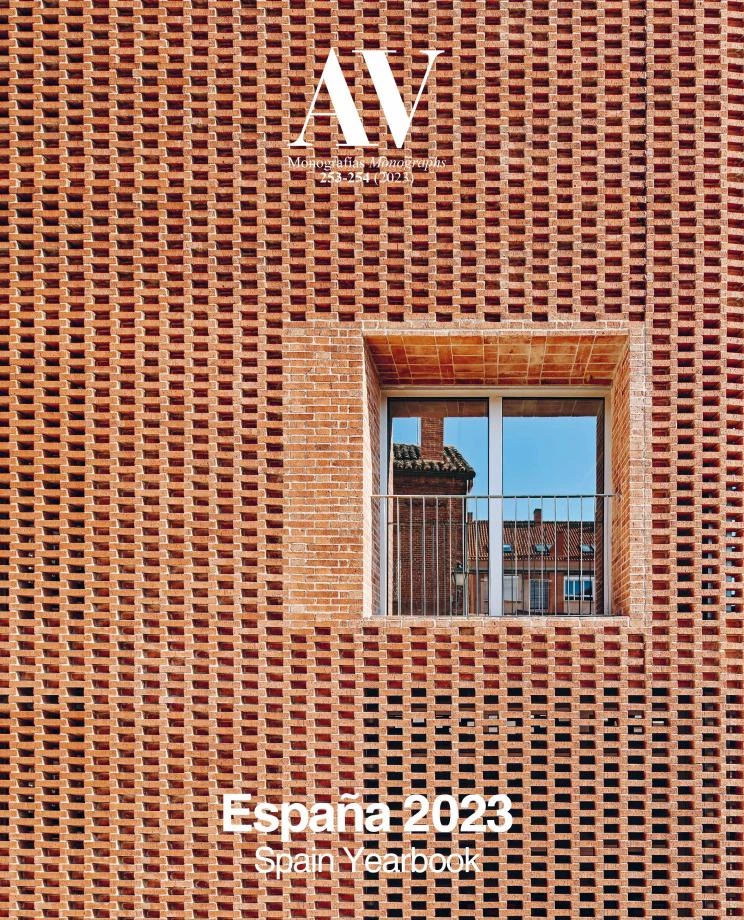

The traditional societies of the Sahel region, whose villages in Burkina Faso are shown here as a nod to Francis Kéré, are being destroyed by political instability, economic fragility, and the exodus of the population.