Three decades ago the library of Sarajevo, disemboweled by shells, was the symbol of Balkanic urbicide, as documented in the 1993 article reproduced on page 24 of this Arquitectura Viva issue. Now it is a bridge outside Kyiv – blasted by the Ukrainian army to complicate the Russian advance, and with a multitude trying to flee the city crammed underneath – that provides the best graphic summary of a military conflict which has destroyed innumerable infrastructures and provoked the exodus of the population. The city of Mariupol, ravaged for control of its port by the Sea of Azov and to close the corridor between Crimea and the Donbas, is the most tragic example of an urbicide that inevitably calls up images of Grozny in Chechnya or Aleppo in Syria, reduced to rubble in the wars of 2000 and 2016.

So far, the three Ukrainian cities most endowed with significant heritage value have suffered little damage: Lviv – Austro-Hungarian Galicia’s mythical capital, whose multicultural character is reflected in the succession of names (Lwów, Lemberg, Lvov, besides Lviv) it has received over the years in the different languages of the ruling powers – lies to the west, far from combat lines; Odessa, the monumental city founded by Empress Catherine the Great on the Black Sea, is strategically located between Crimea and Transnistria – the strip of Moldavian territory on the east bank of the Dniester River that has since 1992 been under the rule of a pro-Russian breakaway government – and therefore dramatically threatened; and Kyiv, linked to Russia’s medieval origins through Kievan Rus, has been especially hit on its outskirts because of the siege it is being subjected to, but the destruction has not yet reached the heart of the city, St. Sophia Cathedral, St. Michael’s Golden-Domed Monastery, the Maidan, or the street Khreshchatyk (whose buildings had been blown up by the Red Army as it withdrew in the war against Nazi Germany in 1941, and later reconstructed by Stalin to create a monumental avenue).

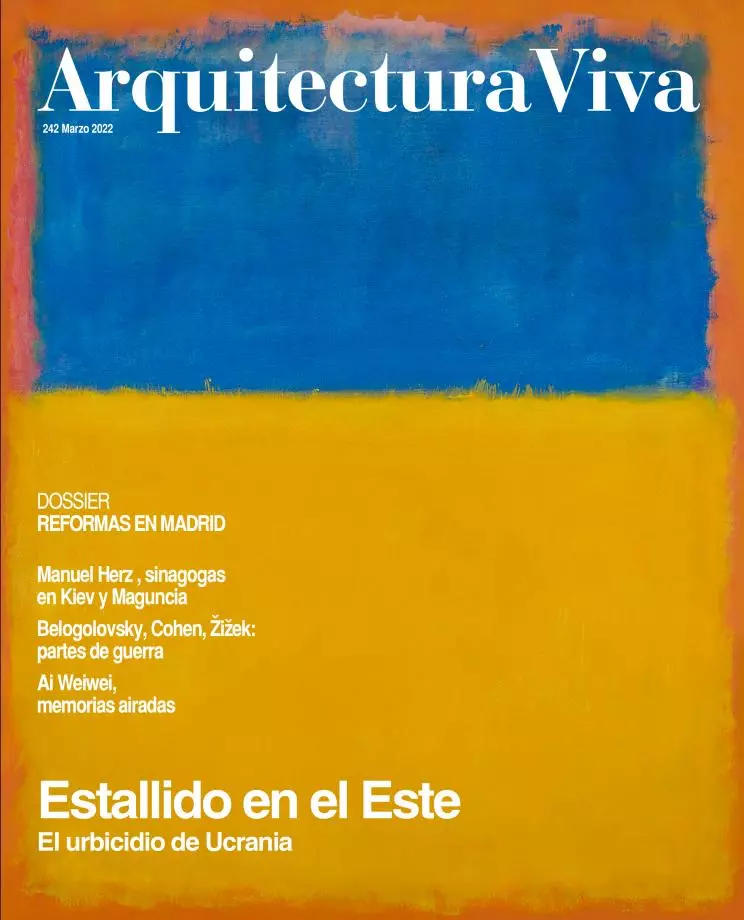

Apart from Mariupol, the most heavily stricken city to date is Kharkov, capital of Ukraine from 1917 to 1934 (when the seat of government was moved to Kyiv), situated close to the Russian border and bombarded since the first days of the war, with probable consequences for the many Art Nouveau buildings that went up during the industrial boom of the early 20th century, not to mention the most important work of the architectural avant-garde, the Gosprom-Derzhprom complex, built between 1925 and 1928 to house the offices of state industry, and included in a chronicle by Jean-Louis Cohen that can be read from pages 46 to 49 of this publication. The image that has made it onto newspaper frontpages and magazine covers is of City Hall, an imposing edifice of sedate classicism that is shown stripped of windows and partly brought down, whose empty eye sockets could also illustrate the dramatic statements, quoted in The Economist, offered by the city’s leading architectural historian, who does not allow mention of her name for fear of reprisals: “Our Kharkov is a new Warsaw, a new Dresden, a new Rotterdam... They want to deconstruct not just buildings, not just infrastructures, not just the Ukrainian state. They want to deconstruct us, the Ukrainian people.”

While the museums hide, protect, or evacuate their most valuable treasures, and while efforts are made to keep the memory deposited in books or documents out of the reach of the current gale of destruction, their architectural containers are tragically exposed to the impact of missiles and bombs, to the expansive wave of explosions that shatter frames and roofs, and to the inevitable aftermath of the flames that wreck interiors, turning into ash the rains of fire that also devastate bodies and souls.