Damage to a residential building after a shelling in Chernigov

This issue has had three consecutive presentations, and none in the end, because this text barely explains a process. After the optimism of January, looking up in awe to imagine the James Webb telescope deploying in space, the gaze had to be brought down in fear towards the army deployed around Ukraine, and ‘The Tanks of February’ describes that moment of anguish. But the tanks started moving at the end of the month, and both the devastation and the European outrage would inspire ‘The Ashes of March,’ commenting the early stages of an intervention that met with more resistance than expected. The continuing conflict urged pondering its causes in ‘Ukrainian Uchronias,’ and the extension of the war to the population with the bombing of cities made us realize that this historic tragedy required a monographic issue, as we did with 9/11, the Iraq War, or the pandemic. Over one weekend we called up friends and colleagues, and the result crystallized into articles, projects, and the memory of past events that also called for political texts.

The accidental triptych of the presentations was completed with the deliberate one of essays, written by a Ukrainian critic, a French historian, and a Slovenian philosopher who approach the conflict from complementary perspectives. Vladimir Belogolovsky, born in Odessa, graduated from the Cooper Union, and based in New York uses his familiarity with the Russian architectural scene to compose a plea in defense of his home country, predicting the renaissance of besieged Kiev ‘when the cannons are silent.’ Jean-Louis Cohen, who has developed a brilliant academic career on both sides of the Atlantic, and whose intimate knowledge of Soviet architecture is reflected in essential books and exhibitions, shares the account of a recent trip to Kyiv and Kharkov where history is inextricably tangled with current events. And Slavoj Žižek, who combines philosophical research with political activism, dispels many of the myths of conventional geopolitics with a vibrant essay that places Europe before the dilemmas of this tragic time.

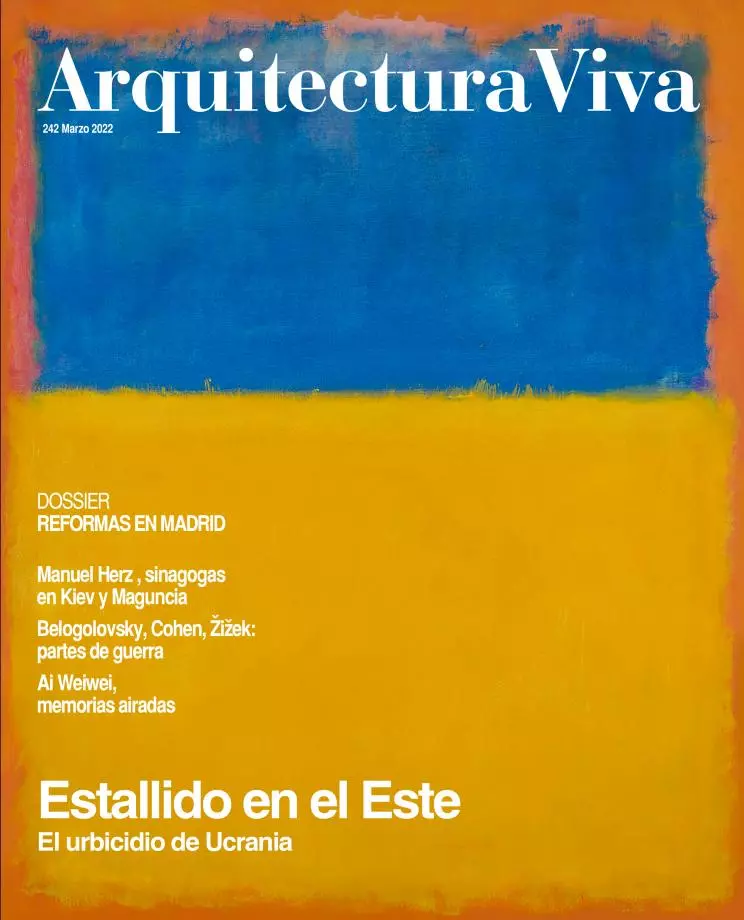

The reaction of architects to Putin’s imperial dream, depicted in Focho’s cartoon, is summed up in a collage of fragments, and the projects are included in the issue with a synagogue by Manuel Herz in Babyn Yar, a ravine outside Kyiv which was the scene of a Nazi massacre of Jews in 1941, and whose memorial to the victims has been exposed these days to Russian bombs; and with another synagogue by the same architect in Mainz, whose Jewish community was also exterminated during World War II, and its temples destroyed by anti-Semitic fury. There is no better oped piece to close the issue than a selection of newspaper frontpages, which have maintained five-column headers to underscore the exceptional character of the event; and perhaps there is no better cover than a painting by the Latvian-American Mark Rothko with the colors of the Ukrainian flag, inverted so that this reference can also become a symbol of the opposition between the creative activity of artists and architects and the destructive violence of war.