To think up the future we have to imagine a different past. With the Ukraine war we have irreversibly entered a new world, but cannot help wondering about alternative events that might have prevented this fatal denouement. The reconstruction of history on the basis of hypothetical data is usually called ‘uchronia,’ on the understanding that if utopia is the non-place, uchronia is the non-time, an instrument with which to project utopia into the past in order to light up different scenarios. Ukraine is particularly suitable to this memory exercise with forking paths, because its geographic indefinition and its multicultural nature makes its historical development exceptionally malleable, causing the current proliferation of uchronias, alternative preterites, struck as we are in our emotions and our consciences by the horror of combat, sieges, and migrations; by the nuclear terror that recalls the Cuban Missile Crisis; and by the destruction of cities that harks back to the Balkan or Syrian urbicides.

What would have happened if Lenin and the Bolsheviks had not ‘invented’ Ukraine, as Putin laments they did? What if the Holodomor famine had not aroused Ukrainian resentment against Stalin’s Russia? What if the anti-Semitic nationalists led by Stepan Bandera, whom many in Ukraine still venerate, had not allied with the Nazis against the Russians in what the latter to this day call the Great Patriotic War? What if the Ukrainian Khrushchev had not handed Crimea over to Ukraine on the third centenary of the agreement between Russians and Cossacks? What if the promises not to expand NATO towards the borders of Russia, when the latter accepted German reunification, had been kept? What if in the dissolution of the USSR the nuclear arsenal in Ukraine had not been removed in exchange for security assurances? What if the NATO summit in Bucharest had not approved future Georgian and Ukrainian membership? What if after Euromaidan the nationalism in power had not discriminated Russian culture and language?

Each of these what-ifs unleashes alternatives for a plural and now fractured country, as would the major geopolitical issues which underlie the current crisis: the Russian fear of not being able to defend its frontiers in the interminable plain of Central Europe; the energy dependence and scant military muscle of a European Union that nevertheless wields the enviable soft power of its prosperity and freedom; and the decline of the American superpower, internally divided and focused on its rivalry with China. However, perhaps the most dramatic questions are today not to be found in the past, but in the future. Will it be possible to ‘finlandize’ Ukraine, letting it join the EU but not NATO? Will Russia claim the Suwalki corridor to connect Kaliningrad to Belarus, isolating the Baltic republics from Poland? Will China mediate successfully or will it take advantage of the opening of a European front to carry out its ambitions over Taiwan? Ukraine stirs up uchronias, but also kakotopias and dystopias.

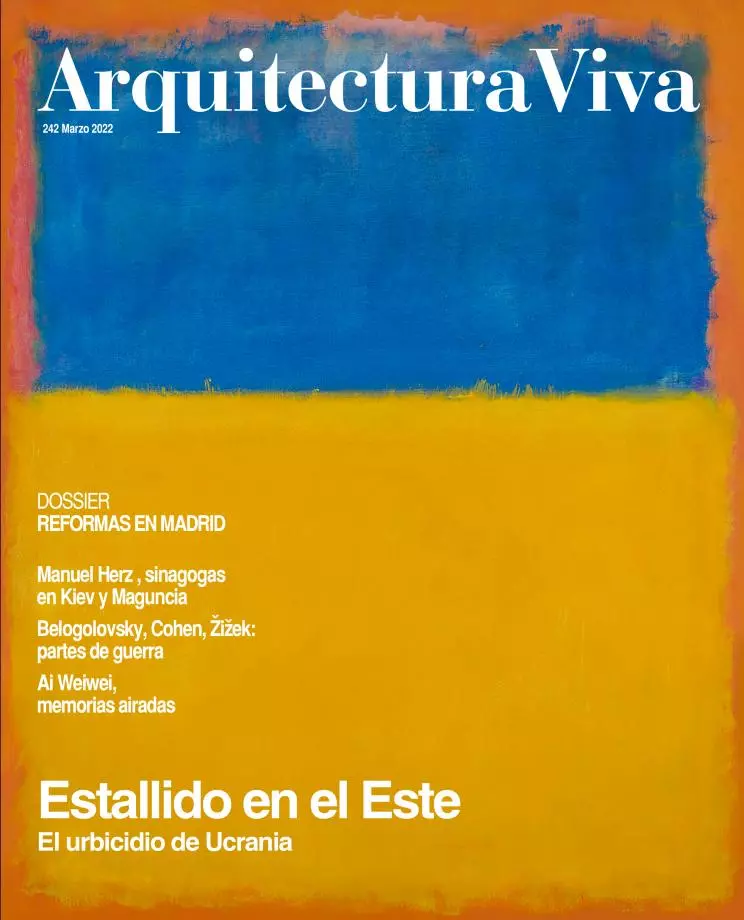

The Russian aggression has resulted in the flight from cities of huge numbers of people, such as those crowding under a bridge outside Kyiv, razed by Ukrainians to make the invading army’s advance more difficult.

La guerra rusa en Ucrania remueve historias y memorias. Barbara Tuchman publicó en 1962 un relato magistral de los 31 días que llevaron a la tragedia en 1914, Los cañones de agosto; 60 años después confiamos en que nadie escriba en el futuro un libro...