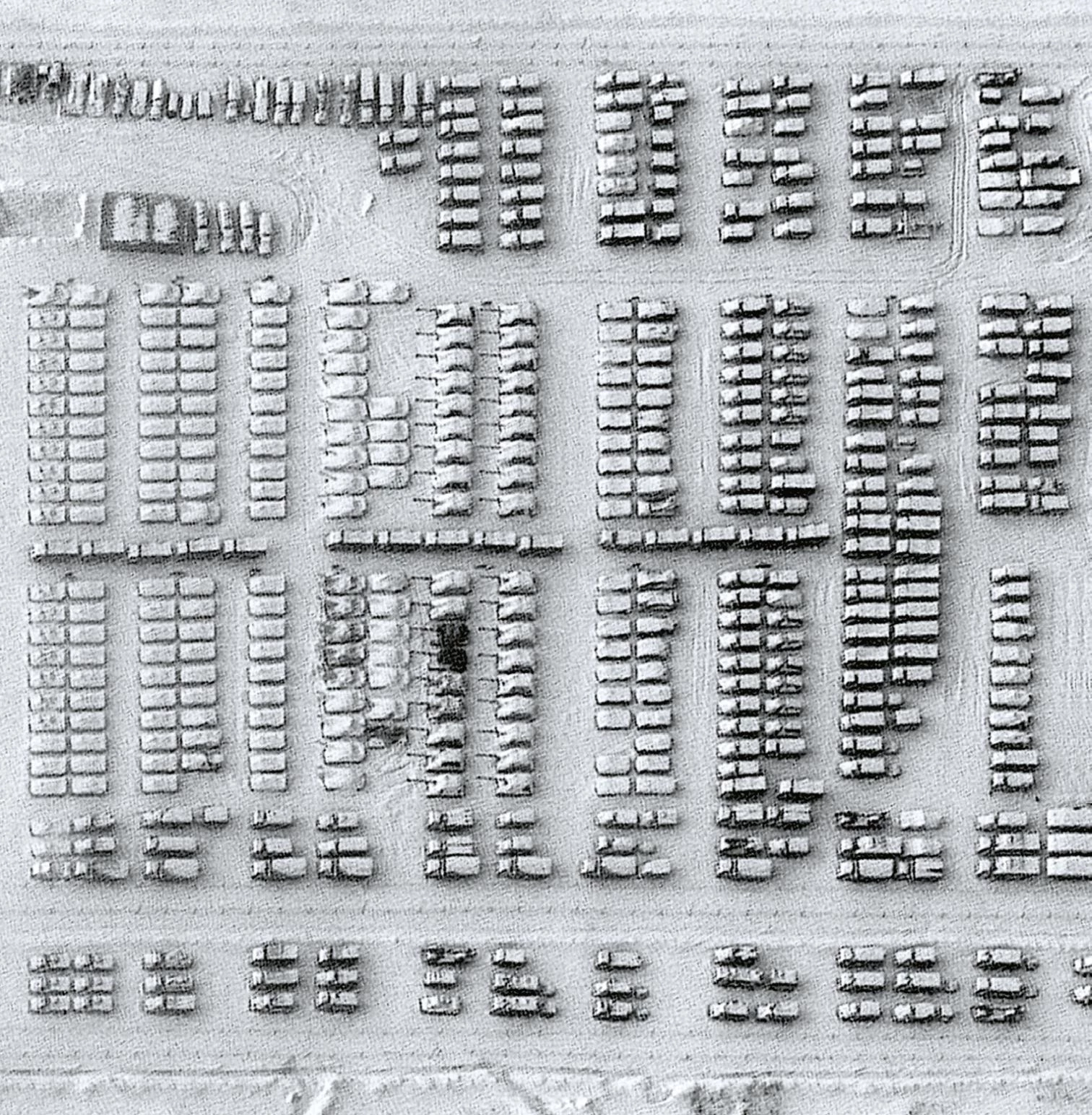

The Tanks of February

The buildup of Russian troops around Ukraine caused a justified alarm in a country that is part, together with Kazakhstan and Belarus, of Putin’s geopolitical project.

© Russian Ministry of Defense / AFP

The crisis of Ukraine reproduces the sleepwalking carnival of the political elites that did not manage to prevent the outbreak of the Great War. Barbara Tuchman published in 1962 a masterly account of the 31 days that led to tragedy in 1914, The Guns of August; sixty years later, we hope no one will ever write a book titled The Tanks of February. And yet, the massive accumulation of soldiers and military equipment on the country’s borders, aside from the Russian fleet in the Black Sea, makes it hard to doubt that some of Vladimir Putin’s geopolitical objectives will be achieved. Perhaps, as Rafael Sánchez Ferlosio reasoned, “when the arrow is in the bow, it must go,” and only the cautious restraint of Americans and Europeans, who have clearly stated that they will not go beyond sending weapons and imposing economic sanctions, allows us to think that the action in Ukraine, as in Georgia or Crimea before, will not spark a global fire, even with the widespread condemnations of the attack.

The tanks deployed around Ukraine performed a dress rehearsal this very year in Kazakhstan, where one week in January was enough to quell the popular uprising in this ex-Soviet country of Central Asia, by far the most important of the five ‘stans’ and the key piece, with Ukraine and Belarus, of the Eurasian project of Vladimir Putin and his shadow ideologist, Aleksandr Dugin, whom we already discussed eight years ago, after the incursion in Crimea, in Arquitectura Viva 161. Belarus, for its part, experienced mass protests in the summer of 2020 after the victory of President Aleksandr Lukashenko, accused of electoral fraud and rescued by Russia, creating one year later an artificial migratory crisis on the Polish frontier, to which thousands of people were flown from the Near East, and now allowing Russian troops to enter the country, with the excuse of joint military exercises, to complete the intimidating siege of Ukraine on the border closest to the capital, Kyiv.

We thought future wars would be either cybernetic, and in fact today troll farms and internet blackouts are being used extensively; or hybrid, like the irregular intervention we witnessed in Crimea, comparable to those of US contractors in Central America or of Russian mercenaries from the Wagner Group in the Sahel. The current conflict, however, seems bafflingly conventional, with the massive mobilization of tanks and troops to gain, boots on the ground, control of the territory. These days of nationalist fervor, which moves so many Ukrainians to claim writer Nikolai Gogol as one of their own, some have recalled the popular film version of his novel Taras Bulba, where the old Cossack after which the novel is titled, performed by Yul Brynner, fights against his son Andriy, played by Tony Curtis, whose love for a Polish noblewoman makes him choose the West and betray his roots. No other seems to be the present predicament of this ‘frontier land’ on the tragic crossroads of war.

The tanks that were to break into Ukraine first set out to repress the popular protests that put at risk the authoritarian and pro-Russian government of Nursultan Nazarbayev’s successors in Kazakhstan.