The Ukrainian crisis has to be tackled with perspective. This is precisely what Daniel Yergin does in The New Map, subtitled ‘Energy, Climate, and the Clash of Nations’ because the confrontation between nations is explained from the angle of its energy and climate foundations. The country now dominating the world’s front pages gets no fewer than ten entries in the alphabetical index, and through them unfolds its relationship with the current geopolitical challenges, the Russian strategy after the breakup of the Soviet Union as well as its political isolation after the annexation of Crimea, and the way in which all of this has to do with Russia’s gas exports and the alteration of the energy landscape by the fracking revolution in the United States. In fact, shale oil extraction through hydraulic fracturing is the subject of the first part, which recounts the conversion of the US into a net exporter of energy through sea transport of LNG, and the new geopolitical map created by this technique.

In successive sections the new map of Russia, drawn by Putin’s oil-and-gas-based grand national project, the new map of China, grounded on the crystallization of the G2 and extended by means of the Belt and Road Initiative, and the new map of the Middle East, where traditional alignments blurred like lines traced on sand, form the other three legs of this admirable cartographic table that helps us understand the planet’s conflicts and mutations from the prism of their energetic and material foundations. Yergin, a leading energy expert who won the Pulitzer for The Prize: The Epic Quest for Oil, Money, and Power, culminates his account with a technical and political assessment of the transition to renewable sources, the metamorphosis of the automobile industry, the effort to develop carbon capture, and the hopes pinned on hydrogen.

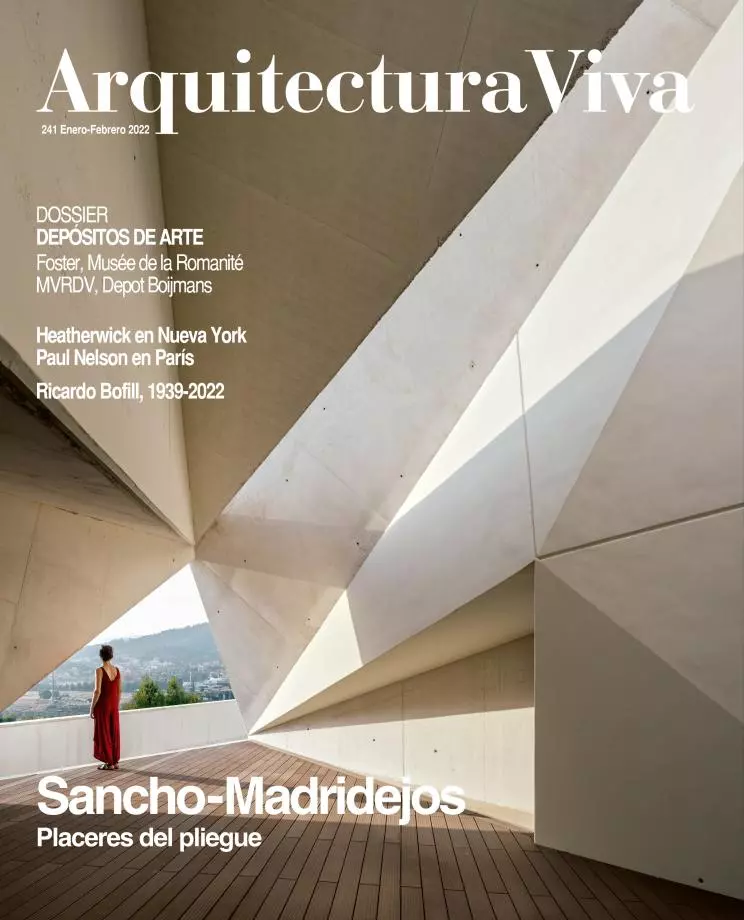

The new energy map shows promises but also threats, and perhaps none as strategic as that which hovers over the South China Sea, to which the book devotes an appendix and where the Chinese claim to sovereignty comes into conflict with the neighboring countries’ right to free navigation: a highly critical situation considering that through its waters and the Malacca Strait sails half the volume of the world’s transport of energy, headed for China but also for Japan and South Korea. Fear that a crisis with Taiwan could lead the US to cut that critical umbilical cord – as it did shortly before Pearl Harbor – makes that zone the most dangerous part of the globe, putting the two superpowers in direct confrontation with one another. Right now Ukraine steals the show, and here, too, Russia’s demands for a protective glacis are intertwined with the energy needs of Europe, which despite the multiplication of gasification plants to serve methane tankers, relies to a large extent on the pipeline networks; a circumstance which has made a symbol of Nord Stream 2, the infrastructure, completed but not yet operational, that would increase Europe’s dependence on Russia. In this magazine we have dealt with Ukraine and Taiwan at different moments (‘Ukraine in Eurasia’ and ‘Thucydides in Taiwan,’ Arquitectura Viva 161 and 237), and hope that the current crisis does not force a revisit.