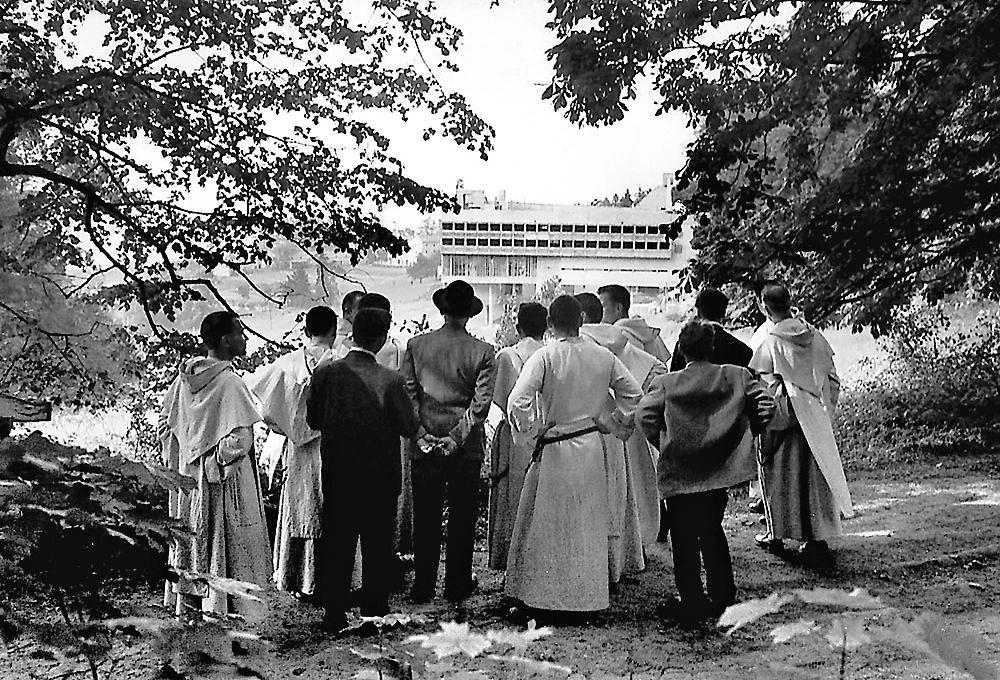

Setting off to inspect the building site, La Tourette

The Unesco Commitee that gathered in Istanbul on 10 July only to cut short its stay because of the 16 July coup d’etat attempt has added five new enclaves to its Heritage of Humanity list, among them seventeen buildings by Le Corbusier and the battery of pavilions designed by Oscar Niemeyer for Pampulha Park in Belo Horizonte (Brazil).

Inclusion in the list is doubly relevant for the world of architecture because, while on the one hand it means recognition for buildings of the Modern Movement within a canon that is already universal, on the other hand it ensures punctilious safeguarding, as a unitary set, finally, of a roster of works scattered about in countries whose laws for protecting architectural heritage is markedly different.

Rejected in two previous applications and now assessed by UNESCO in more predictable terms (works that “reflect the solutions that the Modern Movement sought to apply during the 20th century to the challenges of inventing new architectural techniques to respond to the needs of society”), the Corbusier bid involved the participation of Argentina, Germany, France, Switzerland, Belgium, Japan, and India, and a selection of buildings which, located on three continents and spanning half a century of the career of the Swiss-born French architect, can be considered not only canonical within the Corbusian corpus, but also on their own right masterpieces of 20th-century architecture: from the domestic projects – the Doppelhaus in the Weissenhof Estate in Stuttgart, Villa Savoye in Poissy, on the outskirts of Paris, or the House for Dr. Curutchet in La Plata, Argentina – to the more international projects – the Capital Complex in Chandigarh, northern India, or the National Museum of Western Art in Tokyo – via the great projects in France, such as the Convent of La Tourette, the Chapel of Notre Dame du Haut in Ronchamp, eastern France, or the Unité d’habitation of Marseille.

Valued by UNESCO in terms similar to those of the candidacy of Le Corbusier’s oeuvre, that of the works of Niemeyer covers the pavilions – a casino, a dance hall, a nautical club, a church, and an art gallery – built in the 1940s within the framework of the garden city of Pampulha; buildings which undoubtedly show an indebtedness to the language of Le Corbusier, but expressing the confidence with which Niemeyer translated the modern heritage into a language of his own, more organic and relaxed, and therefore also more akin to Brazilian tradition.

The growth of the list of places protected by UNESCO – which until now totaled 1,031 cultural and natural enclaves – has a Hispanic coda, which in this case points to the origins of architecture. Hence, along with the works of Le Corbusier and Niemeyer, the old dockyard of the British Navy in Antigua and Barbuda, and the Khangchendzonga National Park in India, the 2016 list of new Heritage of Humanity spots includes Gorham’s Cave in Gibraltar – inhabited by the Neanderthals for 125,000 years and attesting to the symbolic capacity of that human species – and the extraordinary dolmens of Antequera, erected almost 7,000 years ago and in the guestbook of which an already aging Le Corbusier, filled with admiration, wrote: ‘To my ancestors.’