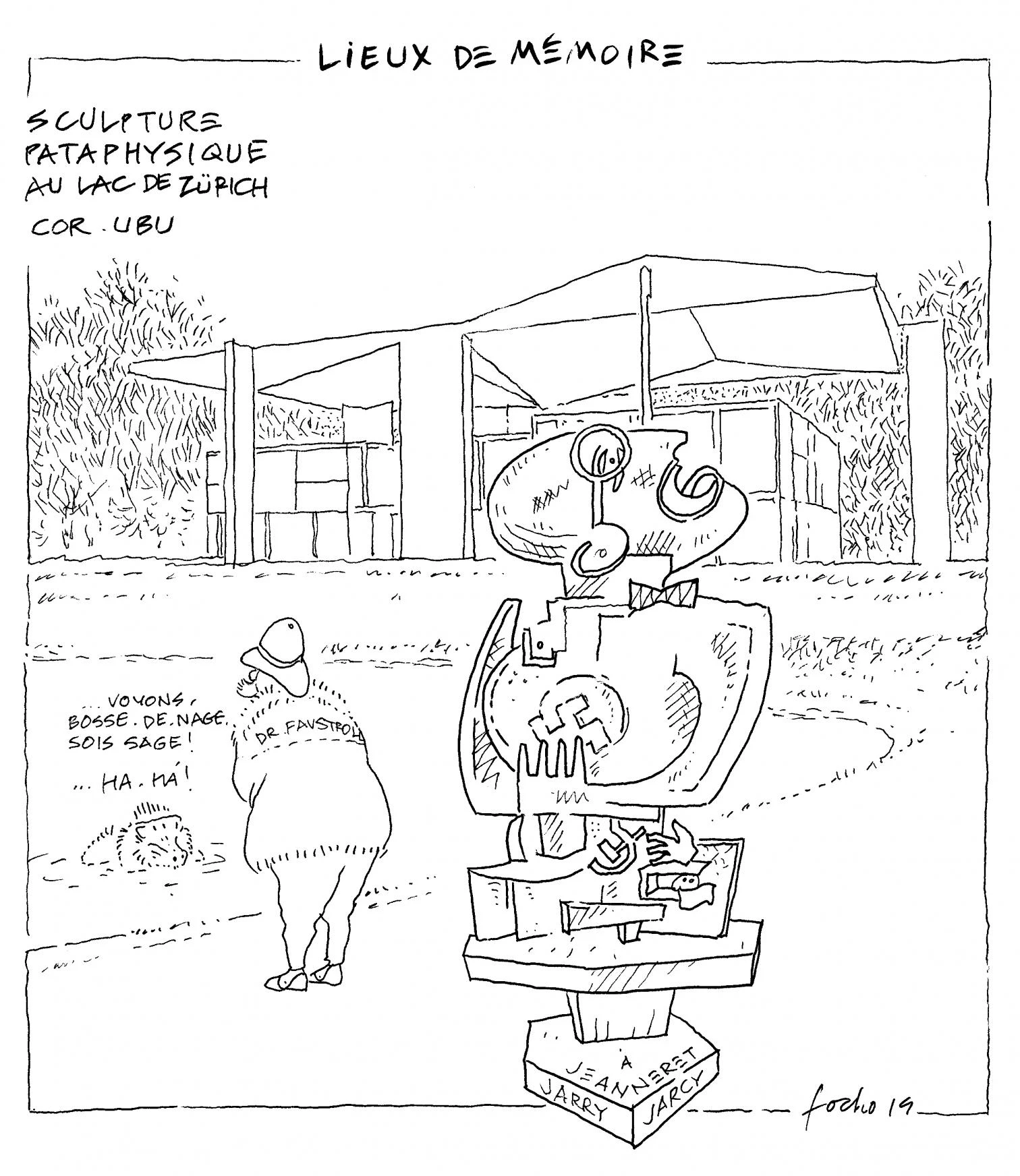

Tributes to artists tend to be post mortem. A case in point is Le Corbusier and his pavilion in Zurich, designed as a Maison de l’Homme in which to display the collection of the gallerist Heidi Weber, but which after opening in 1967, two years after Charles-Édouard Jeanneret’s death, was used for four decades to present his works and ideas, before becoming municipal property and undergoing a careful restoration by Silvio Schmed and Arthur Rüegg which has led to the building’s reopening in May of this year.

The Pavillon Le Corbusier is important for three principal reasons. The first is statistic: it was the last building designed by the Swiss-French master. The second is programmatic: it showcases an extraordinary assemblage of items that together recreate his creative universe; besides his architecture, the museum shows paintings, sculptures, furniture designs, writings, and objets à reaction poétique from his private collection. The third is purely architectural: this is one of Le Corbusier’s most extraordinary achievements – among the few constructions executed with a steel structure – and it is the materialization of the preoccupations and concerns of the architect’s final period, inextricably bound to the idea of the synthesis of the arts. The restoration of this emblem is therefore splendid news, and more so at a moment in time when, because of his disturbing fascist affiliations, shadows have been cast on the figure of Le Corbusier.