Memory and its Mazes

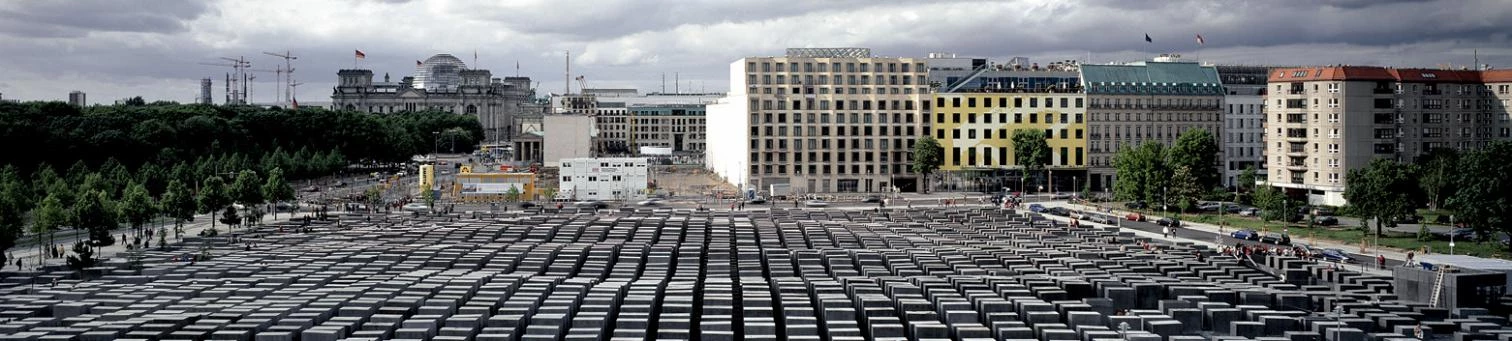

Berlin has inaugurated a colossal memorial designed by Eisenman that evokes the extermination of the Jews with an orderly labyrinth of concrete blocks.

The German pope’s first message was for the rabbi of Rome. Like Wojtyla, Ratzinger has referred to the Jews as “our older brothers”. This historic mutation from militant catholicism – which leaves behind the ambiguous or cautious shadows of Pacelli’s pontificate – atones for the latent anti-Semitism that, after nourishing numerous European pogroms, led to the ‘Final Solution’ of the Nazi regime. María Prankl, who was secretary, in Munich, to the man who is now Benedict XVI, has said that “this pope rehabilitates us Germans in the eyes of the world”. It is this keen sense of collective guilt that underlies the current proliferation of memorials and museums addressing the Holocaust, and that now culminates in Berlin in the form of a colossal labyrinth of concrete that with laconic dramatics evokes the organized, mechanical extermination of six million human beings. Designed by a New Yorker whose grandparents were German Jews, the Memorial to the Murdered Jews of Europe is Peter Eisenman’s most important work. But it is also perhaps the work of the American architect whose authorship most ought to vanish into the severe dignity of anonymity, for only in this way will it genuinely address the tragic dimension of interminable horror.

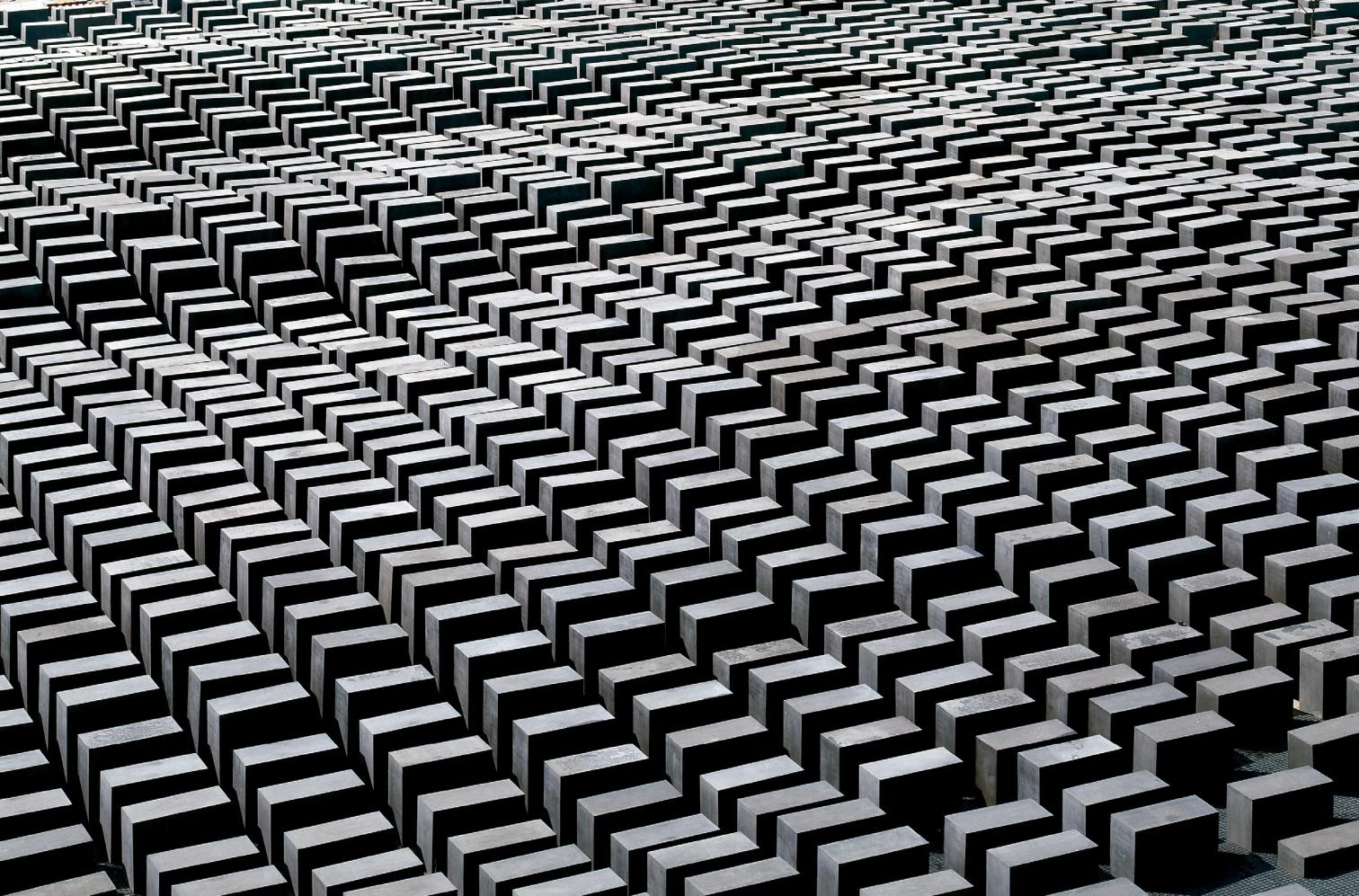

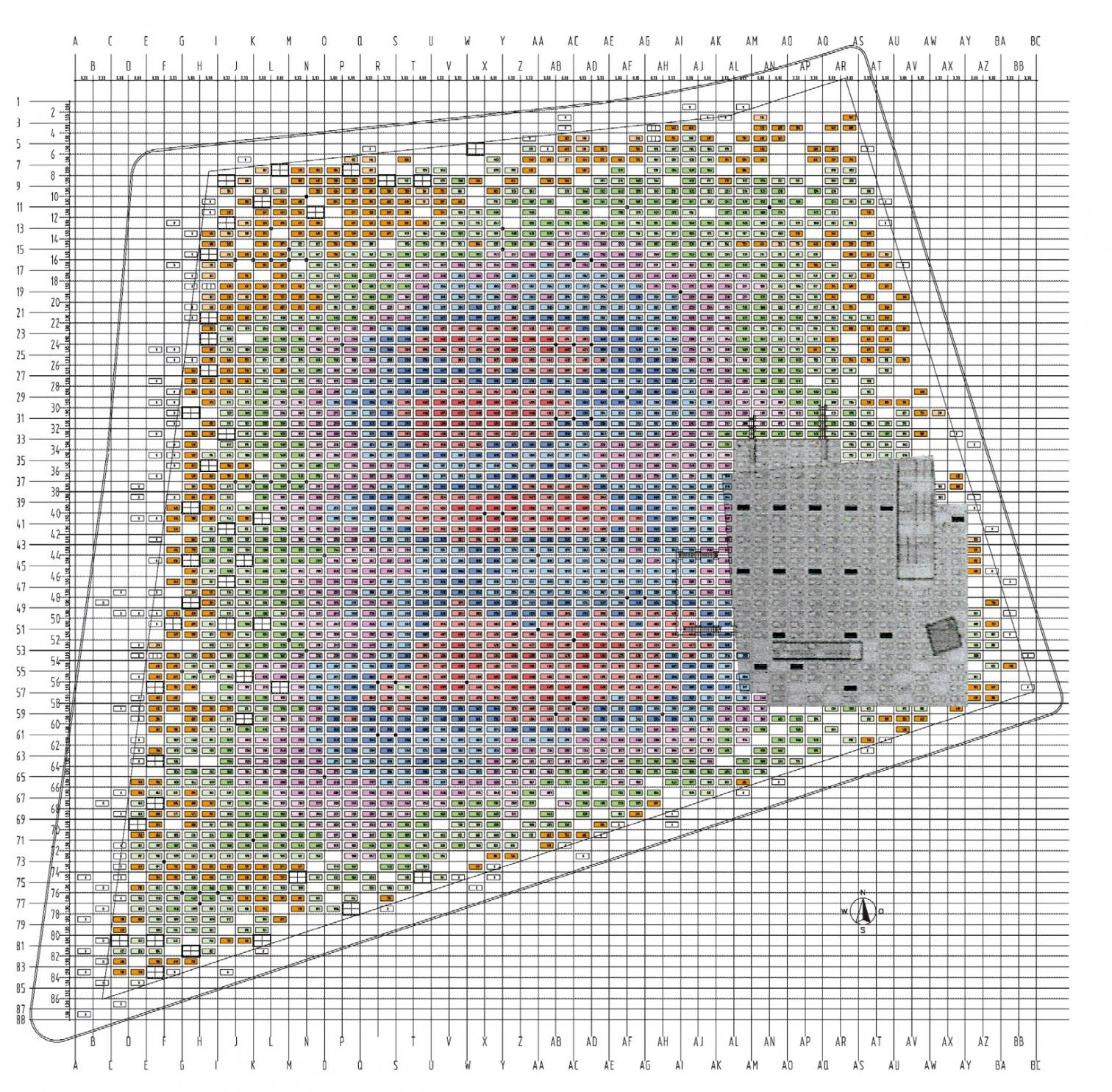

In the close vicinity of the Reichstag, the 2,700 stelae that make up the Berlin memorial trace a gently undulating urban landscape, which seems to recall at the same time a never-ending cemetery and a cultivated field.

In its first version, this multiple and blurred monument owed as much to the grave materiality of the sculptor Richard Serra, who took part in the initial project, as to the geometric complexities of Eisenman. The uncertain grid represented the ‘angst’ of a Jewish cosmopolite, one torn between enlightened repetition and romantic differentiation; the warped surfaces recalled the syntactic games that digital drawing made possible; and the narrow alleys between blocks were understood as a stubborn effort to dig up an artificial landscape. Had it not been built, as was feared many times in the course of a protracted gestation process – interrupted as it was by financial difficulties, by political debates on its abstract nature clashing with the decidedly narrative nature of the usual memorial, and by the scandal caused by the use of an anti-graffiti paint manufactured by the same chemical industry that supplied the Zyklon B used in the gas chambers – the Berlin memorial would have remained Eisenman’s Danteum, similar in its immaterial exactitude to the forest of glass columns dreamed by Terragni, and like it an indelible image in books on the history of architecture. Completed, however, the project has become independent of its author. It has taken on a life of its own as a symbolic heart of the new Germany, the Germany that is at once proudly reunified and emphatically regretful of its ominous past.

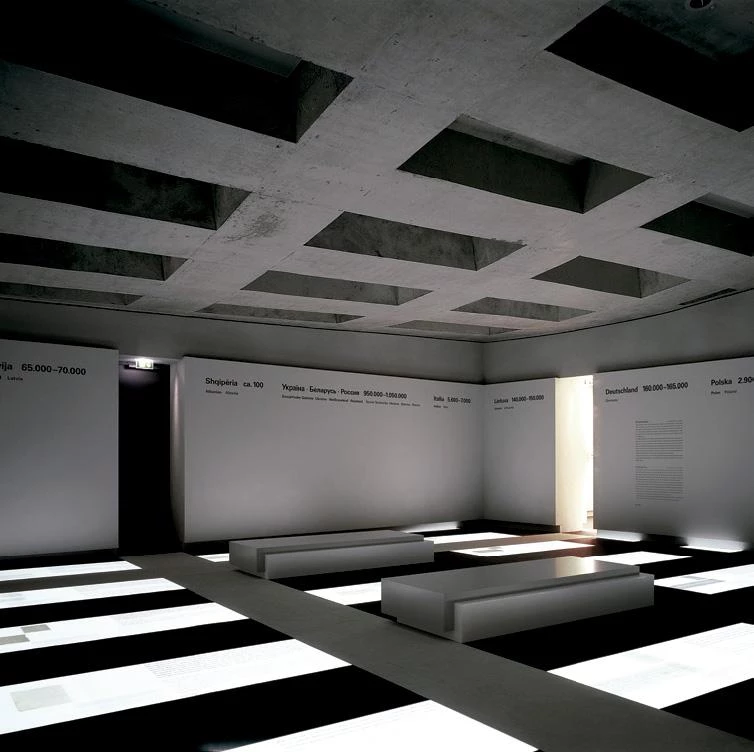

Memorial visitors move among the huge concrete blocks, below which lies a documentation center, with a feeling of unease and disorientation, caused by the absence of references, that geometric order is unable to relieve.

Now in Berlin, the distorted grid expresses the perverse rationality of the Holocaust, with its assembly line of death; the undulating spread of repeated bulks evokes cultivated fields at the same time that it brings to mind the graveyards of war; and the narrow corridors give the visitor an individual experience that monuments of the more conventional kind never offer: beneath a placid, ordered landscape, a hundred paths descending to a familiar inferno. At once a monument and a square, both figure and ground, this cross between sculpture and landscape is actually an architectural and urban installation dug out of the ground that gives the spectator the feeling of being disoriented and lost. Lost in a regular grid, trapped in an open passage, visitors feel anguish in order, and claustrophobia without enclosure. Through their bodies and their senses they perceive the presence of evil in an orderly world. Although many relate the emotional effect of walking between heavy geometric bulks to the sensorial impact of colossal Serra works like the Snake or the Torqued Ellipses, and although others link the undulating rows and the cracked network to other Eisenman projects such as the Columbus Center, the Ciudad de la Cultura de Galicia, or his many ‘excavations’, in the final analysis this memorial is not about singular artistic biographies, but rather about the universality of human experience.

Visitors to an exhibition on Ulay and Marina Abramovic had to enter the gallery by moving between the naked bodies of the artists flanking the threshold. Here, the dressed bodies have to bare their emotions by moving among blocks of concrete that form a maddening maze of order, fluid like a field of lava, to then descend unto an exact, oppressing underworld: a rite of passage that is inevitably associated with death, that is stifling as one goes deeper into the geometric forest and the blocks get taller, the surrounding urban references disappear, and only a piece of sky is left overhead; but that also connects with the spiritual renaissance that follows emotional annihilation, that is liberating as one ascends and leaves the stone garden of tight alleys, which to one looking from afar fades into a friendly wave, in such a way that the memorial blurs its lines and becomes undefined, becoming part of that vast ocean of pain and tombs that lies under Berlin. Jacques Herzog may be right in suggesting that the memorial’s walking and tactile experience be exacerbated with a soft ground of earth or gravel that would respond to each step and stress the presence of the blocks as icebergs of concrete rising from the underworld. But the current paving stones seem to suffice to push the visitor toward a precipice of anxiety and malaise.

It is hard to decide how to express the memory of terror. Both the floral altars of Hiroshima and the flaming rails at Auschwitz are, as theaters of memory, far more effective than the real-estate theme parks of New York City’s 9-11 and the squalid, nomadic forest of the absent commemorating Madrid’s 3-11. But Spain is now living a spring of tombs removed, history revised, and monuments questioned that threatens to turn the amnesic amnesty of the transition to democracy into a battlefield of opposed, hostile memories. In contrast to the collective repentance that Germany requires of its citizens, or the act of contrition that orchestrated demonstrations in China demand of Japan, Spain’s conflict of symbols goes back to a civil war, and who knows for sure if beneath the ashes of history the embers of resentment that feed the fires of spirits and bodies have really been extinguished. Berlin with this memorial of atonement, just like the Bavarian pope with his fraternal reaching out to previously scorned confessions, paves a path of reconciliation of identities, beliefs, and memories that can serve as an example for this highly flammable country of fierce streaks and hot tempers. German lessons may not be what we are expecting at the moment, but the Berlin labyrinth can help us find our way through our own familiar labyrinths.