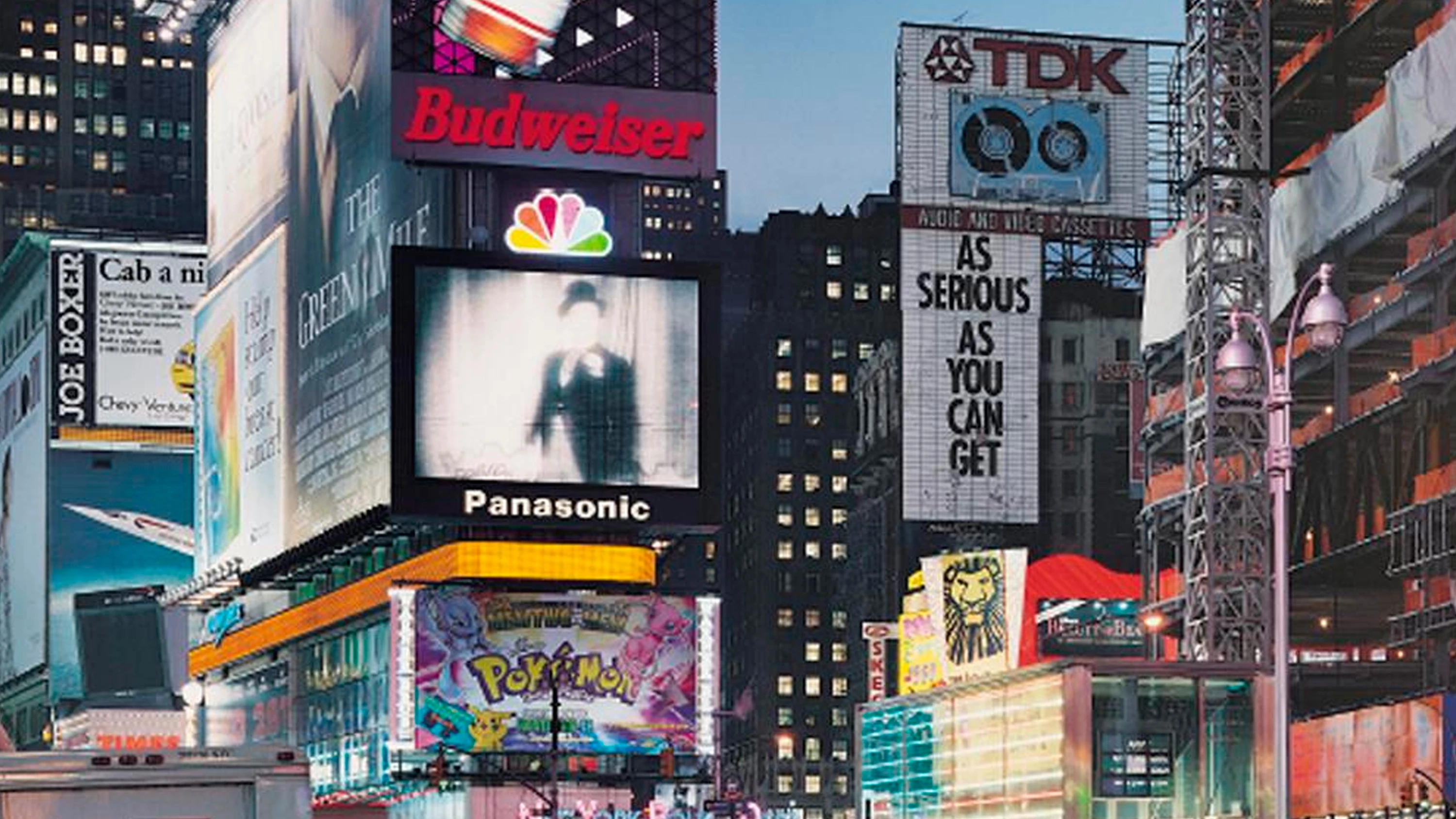

The Big Apple has a neonheart. If bitten, its pulp glows: it doesn’t nurture, but it illuminates. Transformed into a spectacle and a replica of itself, the New York which was built with the substance of myths is today the engine of the dream industry, and that which Philip Roth calls «the triumph of the surface» finds its most accurate setting in Times Square, a neon knot to tangle the dying animal in sedating simulations that entail «the triumph of trivialization over tragedy». Over a century ago, another Roth, Henry, contemplated the new world on which he set foot through Ellis Island with the wide open eyes of the terrified child, and chose to call his painful wakefulness sleep.

This was the same city that a newly wed Juan Ramón Jiménez called a «filthy-nail tomboy», a «trust of bad odors» with «dizzying bright color displays in the sky», and which in Broadway led the poet to question: «Is it the moon, or is it an advertisement of the moon?»; the same one that the Dos Passos of Manhattan Transfer presented with swift gusts as a frenzied and fleeting metropolis; and the same one that García Lorca described, from the top of the Chrysler building, as «a gathering of sewers where the dark nymphs of anger scream out loud», a New York of «mud and fireflies» that only alleviates its «imperfect angst» when «the snow of Manhattan shoves away the signage and sheds pure grace on the false ogives».

That insomniac and ominous metropoli fascinated European architects as much as poets, and the travel impressions of Behrens, Neutra or Le Corbusier in the twenties and thirties exude an ambiguous attraction towards its muscular and chaotic violence which is not very different from that which inspires Lorca’s or Mayakovski’s texts. Yet it is a distant admiration, tainted by the estrangement and unease before a rough and strenuous city, which in the eighties, Paul Auster still considered «the most forlorn of places, the most abject. The brokenness is everywhere, the disarray is universal... The broken people, the broken things, the broken thoughts. The whole city is a junk heap».

One would have to wait until the nineties for New York to turn into the gentle metropolis of its myth, Woody Allen’s Manhattan and the Brooklyn of Smoke, a neurotic and hygienic place that is dyed with Dick Tracy’s candy colors and mimics 42nd Street with such trivially correct simulacra as the cultural references that fill the New York notebook published by José Hierro when the 20th century was coming to an end. From Roth to Roth, and from Jiménez to Hierro, the inner vision of writers and the outer glance of the poets reveals a transition from drama to comedy that marks, in architecture as in life, the triumph of the surface and the bittersweet victory of neon. Surely it is not a tragedy.