Pentagonal Peninsula

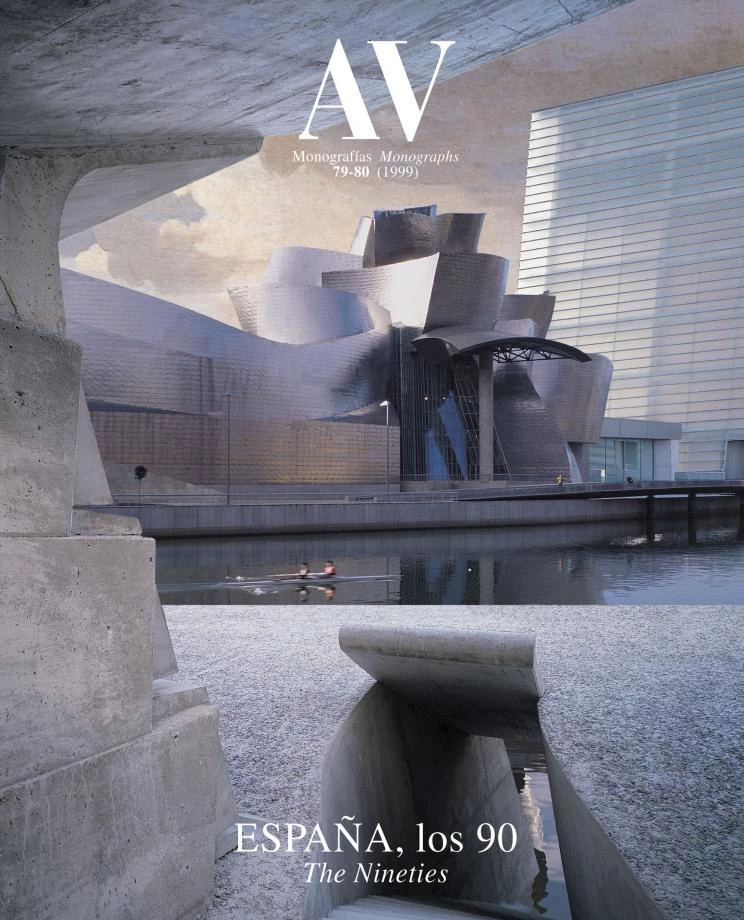

The very significant reforms made in the past decade have failed to stop ‘Spanishness’ from being Spain’s main attraction outside of the country.

In Barcelona, replicas of traditional architecture in the Pueblo Español repeat the Spanish leitmotifs coined by 19th-century travellers and criticized by the Italian scholar Mario Praz in his book, Penisola Pentagonale.

Mario Praz visited Spain, for six weeks, in 1926. His impressions were published in Milan two years later in a book entitled Penisola pentagonale, which then appeared in 1929, in London and New York, as Unromantic Spain. This cruel yet tender publication is the expression of a sadistic love for Spain. The reading of its caustic pages causes both pain and pleasure; like certain deviant passions, it offers hurtful penetrations and violent enlightenments.

In the twenties, as would again happen in the eighties, Spain was in. Unanimously considered ‘genuine’ and ‘deep’, it was invariably paired with Italy, in away resembling the relation that had once existed between Greece and Rome. With the image of the peninsula fabricated by German and French romantics now firmly ingrained, Spain was to many, in the words of Kurt Hielscher, “probably the world’s most picturesque nation.”

The Spanish fad was particularly hot in Anglo- Saxon countries - Praz was based in England at the time. Our traditional architecture and interior decoration caused a rage in the United States, especially in the domestic realm. In the same year of Praz’s journey, Waldo Frank published Virgin Spain, a lyrical interpretation of the old notion of picturesque Spain. The book of the Italian scholar proposed the complete opposite: the demolition of the legend of a romantic Spain.

The fascinating, coloristic view of Mérimée, Musset or Hugo takes on sinister tones in the portrait drawn by Praz, who is particularly fierce in his mockery of Théophile Gautier’s Voyage en Espagne and its echoes in the prose of travel agencies. The brutal sarcasm of the Italian paints a Spain that diverges widely from the depiction expected by foreign travelers: physically monotonous and socially corrupt, Spain is a nation of “pragmatic people, infinitely less romantic than English spinsters or bank employees on holiday.”

Monotonous are the dusty landscape, the brownish- gray earthen paintings, El Escorial’s repeated windows and the poetry of the mystics - “an insipid litany.” Monotonous is Don Quixote, super-monotonous the playwrights Lope de Vega and Calderón, monotonous the food, the spectacles and the feasts, with boredom coming to a peak in Seville’s Holy Week and the bullfights. “If there is a European country that lacks what it takes to be picturesque, namely the quick succession of varied effects, that country is Spain.”

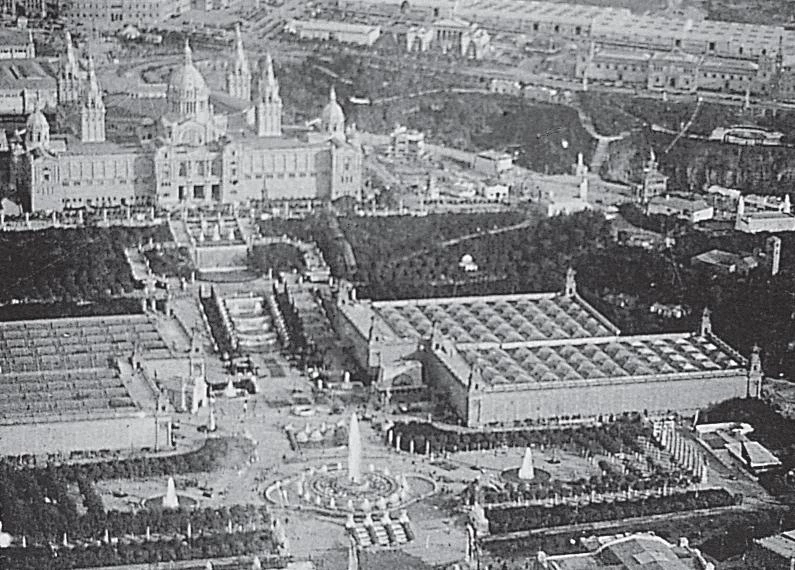

The grounds of the 1929 Universal Exposition were sculpted into the slope of Montjuïc, the same hill which was later selected as the main athletic scenario for another huge Barcelona event, the 1992 Olympic Games.

The social sphere is no better. Hospitality is hypocritical, and courtesy, mere protocol. Spaniards are lazy and live an eternal Sunday. To Praz, no depiction of Spanish life is more accurate than Benavente’s Los intereses creados. Life is a web of interests, and nothing must be done to upset it. Everything works through the string-pulling of friends. “For practices of this kind,” he writes, “there is an ugly Italian word that will scandalize Spaniards: the word Camorra.”

This ferocious and paradoxical text is interspersed with what the Hispanophobe Edmund Wilson called il prazesco, a peculiar combination of the macabre, monstrous or grotesque with a morbid sensuality and an eroticism of agony and ecstasy. It leads the author to strike a profoundly ambiguous relation with the description of Spanishness that he used as a title for one of the chapters: “du sang, de la volupté, de la mort”. For blood, voluptuousness and death simultaneously repelled and seduced this perverse, exquisite, angry erudite who traversed the peninsula in 1926.

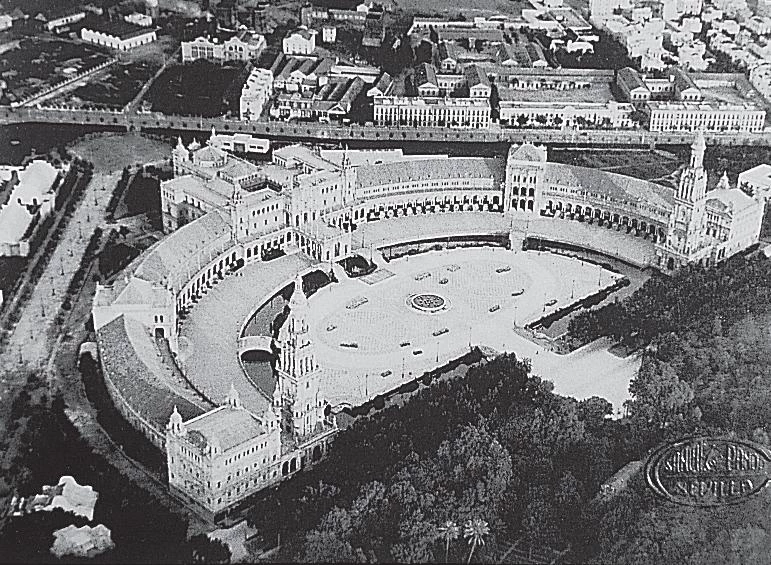

That was, incidentally, the high moment of Primo de Rivera’s dictatorship. The military cast had given way to a civilian one, the Rif was at a calm, a social program ‘in the Italian style’ had introduced labor reforms and large-scale economic projects had been launched - such as the regulation of the main rivers through dams, the road building special plan and the 1929 world’s fairs in the cities of Seville and Barcelona. “The primary aim of the dictatorship,” Praz rejoices, “has been to do away with the traditional bases of national life, and turn a new page: a European page.” But the traveler is skeptical regarding the results of the endeavor, and has reason to be.

The extroverted Andalusian general’s national or perhaps Europeist project for reform was helped at first by an exceptionally favorable world economic situation, but would fail altogether, as we know, shortly after the latter collapsed in 1929. The peninsular exhibitions of that year, like many costly public works, were lambasted as megalomaniac, and the foolhardiness of the budgets that were drawn up to fund them would reveal itself in full. The regime alienated the middle classes, the Catalan and Basque nationalists, and the intellectuals. It covered up financial scandals, repressed students, and harassed the press. When the peseta finally dropped, so did Primo de Rivera, and Spain fell out of fashion in the world.

Why resist the temptation to put down some features shared by the ‘rolling twenties’ and the more recent ‘pink decade’ of the eighties? Economic prosperity, the reform project, Spain’s international popularity, the promotion of Barcelona and Seville... Of course there are as many differences as there are similarities and it would be extravagant to draw a parallelism. But it must at least be pointed out that on both occasions, the reformist mood prevailing within was accompanied by a traditionalist projection abroad. Spain wished itself modern but was perceived as folkloric.

Inside, the 1992 jubilee deliberately avoids Hispanic references, preferring to situate the Columbian adventure in the more general context of scientific and technical discoveries, and present it as an exploit of Europe’s Renaissance. Both the Barcelona Olympics and the Seville Expo eloquently assume an ecumenical stance, removed from any affirmation of Hispanicism: Catalan in one case, Andalusian in the other, universal in both, but never Spanishness as the guiding thread.

Frente al folklorismo que marcó la exposición Iberoamericana de 1929, la Expo sevillana de 1992 huye de toda referencia hispana para apostar por una arquitectura sin fronteras atenta al progreso tecnológico.

Outside of Spain, however, it is the “eternal” and castizo tradition that defines our image to this day. Spain continues to be El Escorial, the Alhambra, bulls and flamenco, paella, Gaudí or Toledo, San Juan de la Cruz, Don Quixote, Murillo or Zurbarán: more or less the same figures, places and things that the avenging anti-romantic inquisitor of the picturesque, Mario Praz, lashed at more than a half-century ago. Spain’s lure still rests in ‘Spanishness’, in the continuity of tradition.

In spite of everything, the idea of celebrating the 1992 commemorations on a Europeist clef seems less probable than it did a year ago. Delays in the process of European construction - caused as much by developments in the East and German unification as by the renewed awareness of the continent’s vulnerability in energy matters that the Gulf crisis has sparked - have cursed the magical date of Jacques Delors: ‘92 is now a bit less European and a bit more American.

Indeed, we are likely to get to that 500th anniversary with an economic panorama hardly suited to rejoicing. The inevitable cuts and the general climate of melancholy make a celebration with a marked Hispanic and cultural profile more plausible than one that maintains the current cosmopolitan and technological project. The austerity to come will have to be symbolic besides material, if it is not to risk awakening old phantoms and dormant regional quarrels.

The sudden halt of the mad race of the eighties can perhaps be a time for reflection, and a chance to complement the economic debate on budgetary adjustments with a political debate on priorities, contents and values. Economic modesty must not constrain, but stimulate, cultural ambition. Maybe by then Spain will have ceased to be in vogue in the world, but this is no big deal if in exchange it becomes so within its own borders.

In the preface to a 1954 edition of his book, Mario Praz evoked the tenderness that Peter Karfeld’s photographs of Spanish landscapes had aroused in him, “a tenderness I imagine to resemble that of 19th-century romantics enamored of Spain... and even that felt for a person one has at the bottom of his heart always loved, but hurt a little.” Such an aggressive, violent love is, I think, preferable to the indifference with which we are prone to contemplate this pentagonal peninsula.