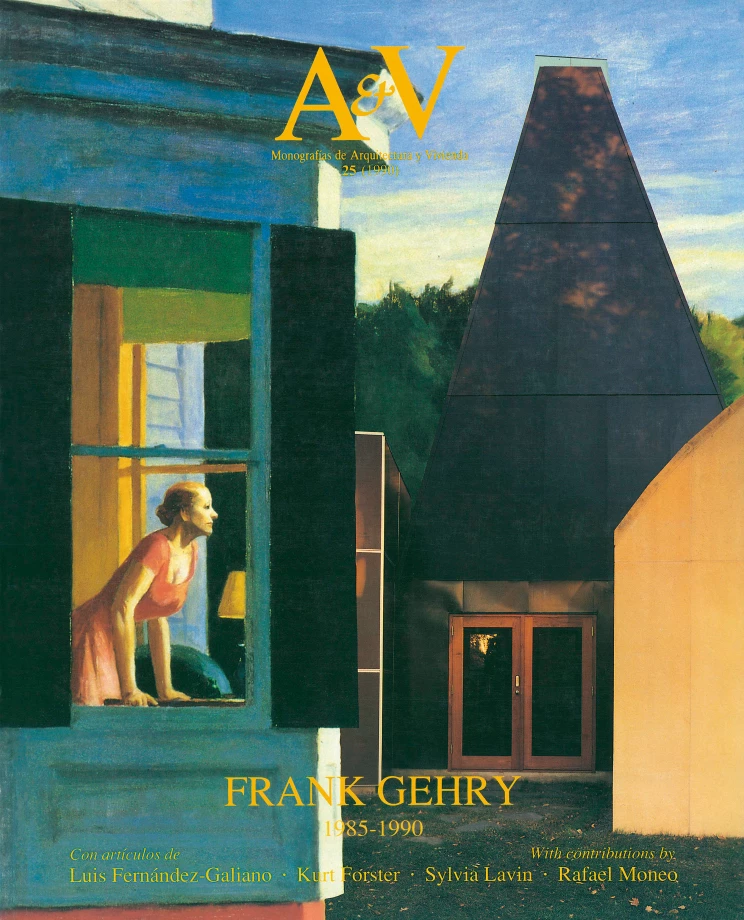

Schnabel Residence, Brentwood, California, 1986-1989

The pieces and parts of architecture have been compared to the human body and its limbs at least since classical antiquity. When we speak of a lintel supported by straight or atlant feet, or when we think of a beam supported and braced with arms, we give life to a static order through the analogy of the effort and bodily labor required to lift such parts.

This analogy does more than perpetuate a primitive way of imagining the interaction of invisible forces: it also indicates the spacing of gaps and masses, and even generates a sense of symmetry, balance and tension. These notions have become so commonplace in language that a special effort must be made to restore their corporeal reality in the experiences we have of buildings. Our ability to appreciate inanimate objects in their relations to animate bodies depends, almost by contradiction, on our ability to circumvent the power of language...[+]