Epiphany of the Perfume

The city of the third millennium is prefigured in malls, cathedrals of a new religion of consumerism that colonizes the old urban space with seductive images.

Lost in the crossroads of the century, we look upward for signs to guide us. But in the urban jungle, all our eyes stumble upon are billboards announcing telephones, automobiles, watches, liqueurs or perfumes, orienting our steps toward the basilicas of the cult of consumerism, which is where the new times manifest themselves in all their insolent splendor. This epiphany of the world exchanges incense and myrrh for the volatile fragrance of fashion trademarks, which establish with their aromas the limits of a promised land of carnal felicity. Occupying the chapels of the horizontal cathedrals that constitute the public space of our epoch, the mercantile emblems of desire construct a virtual architecture of hedonistic pleasure: warm interiors without facade or fatigue, faceless organs permanently offered. Resembling random spaceships or aircraft carriers, malls anchor themselves in the undefined territory of urban peripheries, to soon become the genuine city centers, luring a swarm of vehicles which cling to their perimeters like iron filings around a magnet.

The magnetic force of large shopping cen-ters pulls architects as well, who are not spared the vague attraction of these colossal organisms that multiply uncontrolled, and who are also seduced by the rare capacity of trademarks to conquer consciences. More and more the young or the elderly make these spaces their meeting point, and more and more of us perceive the world through the prism of commerce. With his students at Harvard the Dutch Rem Koolhaas has actually studied commercial architecture, and he has tried to put his conclusions to practice by designing boutiques in New York, Los Angeles and San Franciscofor the Italian firm Prada, besides its website Prada.com; an effort parallel to that of the Swiss partners Jacques Herzog and Pierre de Meuron, who have built a large store in Tokyo and warehouses and workshops in Italy for the same company, or that of the Japanese Kazuyo Sejima and Ryue Nishizawa, with the beauty shops of its chain of boutiques. Promiscuity between architecture, art, fashion and consumerism no longer takes anyone by surprise, and with the same naturalness we accept Armani starring in the Guggenheim’s programming or Koolhaas himself collaborating with Herzog & de Meuron to build one of Ian Schrager’s boutique-hotels, previously always entrusted to the French Philippe Starck.

Commercial activity shapes the public space of our times. Similar to spaceships or aircraft carriers, these cathedrals of consumerism erected in the peripheries are soon transformed into genuine urban centers.

Time ago I predicted that architects would one day lend their names to perfumes, and Oscar Tusquets warned me that the playful Starck would be first to do so. But today, harsh Herzog proposes colognes with the scent of asphalt, and subversive Koolhaas directs all his energy to the designing of Prada’s fitting rooms, theorizing in the meantime that the mall has become the main ritual of modern life, the escalator the most important architectural artifice of our times, and urban advertising the best medium by which to inject the culture of brands into public conscience. In his ongoing Bordeaux exhibit on the contemporary city, set up with a multidisciplinary team and designed by Jean Nouvel, the Dutch architect explores the destructive impact of war, information and consumption, showing how the physical and visual devastation of cities by advertising and commerce is not much less pronounced than that caused by military catastrophes.

The American city is documented in this exhibit through extraordinary aerial photography by Alex S. MacLean, a refined and critical interpreter of territorial transformation who changed his architectural studies in Harvard University’s Graduate School of Design for a Cessna 182 plane and a camera, and who has done with mutations of landscape what the Brazilian Sebastião Salgado has done with migrations of people: manifest its overwhelming dimension through a visual register of moving beauty, emotion and relevance. In his images of the unexpected and savage geometry of city peripheries, many shopping centers appear like battleships stranded in interminable parking lots, but none is as memorable as Katy Mills Mall, photographed in 1999 for the Houston journal Cite, where the docile meander of the belt that skirts it and the arbitrary outline of its perimeter hardly conceal the fact that it is no more than flat architecture, crushed to the ground like a cartoon character ran over by a steamroller let loose.

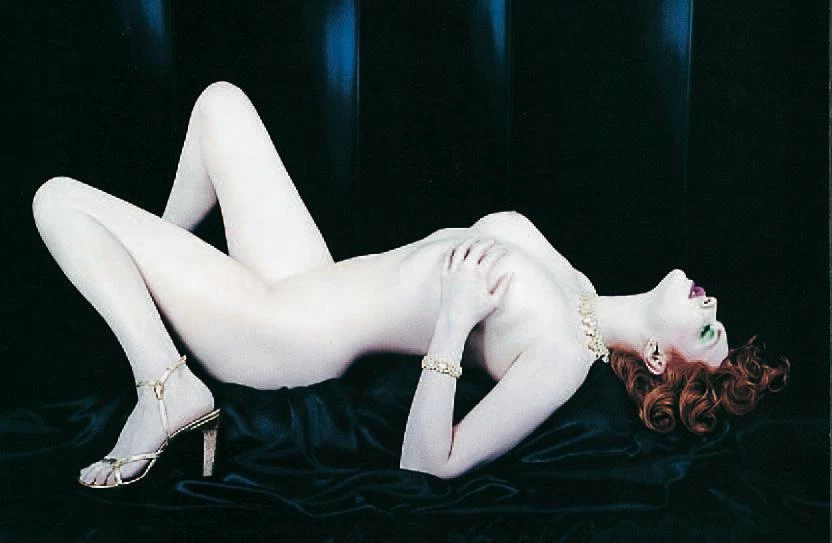

The nude image of the model Sophie Dahl advertising an Yves Saint Laurent perfume was banned in the United Kingdom. Only the Osborne bull spared the removal of billboards on Spanish highways.

But inside this horizontal expanse is a powerful whirlpool that sucks up the traffic of surrounding highways and clusters cars around it, gobbling up passengers into a luminous belly of flat spaces and flat experiences. In his latest novel, the Portuguese José Saramago likens malls to the platonic cavern, deploring its superficiality and triviality. But he also concedes that to be expelled from them – exactly what happens to the main character of his novel, a potter whose wares are excluded from the mall – is to be thrown to the margins of the city and civilized life. Indeed, beneath the flat appearance of the mall throbs a desirable organ whose gravitational force is altering the constellation of objects and the fabric of networks the city is made of, and which in the end gives the commercial center a central position in the new urban galaxy. The caustic French writer Michel Houellebecq, who has described a society composed of “elementary particles” in unequal competition for economic and sexual success, believes that we can only understand the present world as a supermarket, and argues that the mission of contemporary architecture is none other than “to build the sections of the social hypermarket.”

Both pessimistic in their diagnosis, Saramago and Houellebecq differ, however, in attitude, which inevitably evokes that of their fiction characters: archaic and resistant in the case of the Portuguese, whose essential integrity is tempting to link to the material emphasis of Swiss architects, including a Herzog nourished by the tenacity of the landscape and the organic; neurotic and narcissist in the case of the Frenchman, whose accommodating agitation and apathetic crusade against libidinal liberalism have something in common with the skeptical supermodernity of Dutch architects, including the schizophrenic Koolhaas of boutiques and junkspace. And if Herzog & de Meuron and Koolhaas have competed in Tenerife, with a K.O. victory for the Basel team, the two writers have shared literary territory on another Canarian island, Lanzarote. But whereas Saramago was conscious of the mineral beauty of a landscape rebelling against plunder, Houellebecq understood the isle as a vacuous venue for the photographic safaris and erotic adventures of an accidental tourist; at the center of the world, true, but a world that knows itself to be “medium-sized.”

Maybe the Frenchman did not know that Lanzarote was once the scenario of an uprising against the commercial colonization of territory. The first publicity billboard to be put up there was knocked down, and so it was that the island managed to protect itself from the profane canophony that proliferates in our defenseless cities– yesterday on empty lots, today on the edges of parks and gardens, tomorrow on every tree and cloud. An invasion on the whole tolerated which only becomes controversial when the image on display offends the modesty of some or the political orthodoxy of others, but never when it degrades the landscape or pollutes the city. A socialist minister removed billboards from Spanish highways, and he was less praised for that than for the subsequent sparing of the imposing Osborne bull. Now the United Kingdom has banned an Yves Saint Laurent perfume advertisement that shows the model Sophie Dahl in the nude, yet the polemic has centered more on the prudishness of the British than on the unstoppable growth of urban billboards.

Tepidly erotic like any perfume promotion – whether Calvin Klein or Rochas, Dior or Dolce & Gabbana – and less sexually explicit than those of Gucci or Carolina Herrera, the censured ad is an emblematic representation of consumerism’s promise of pleasure through the half-open, made-up and bejewelled body, where only the calligraphic arabesque of the pale skin on the dark satin backdrop sensually and esthetically differentiates the model from the golden chaste bubbles of Freixenet. If we were to abolish the urban billboards, perhaps some would ask for Sophie Dahl to be spared. This would not be a bad compromise. The Osborne bull might carry away a British maid donning only a drop of French perfume, and this image of Europa could well illustrate the flat and seductive continent of the third millennium, while we survivors of the preceding one extinguish ourselves painlessly in archaic cities also spared of the obscene impact of billboards. What a good Christmas story this would make, the best Christmas present.