Skyline Wedding

The wedding in Madrid of the Prince of Asturias has sparked a debate on the ceremony venues, but not on the relationship between democracy and spectacle.

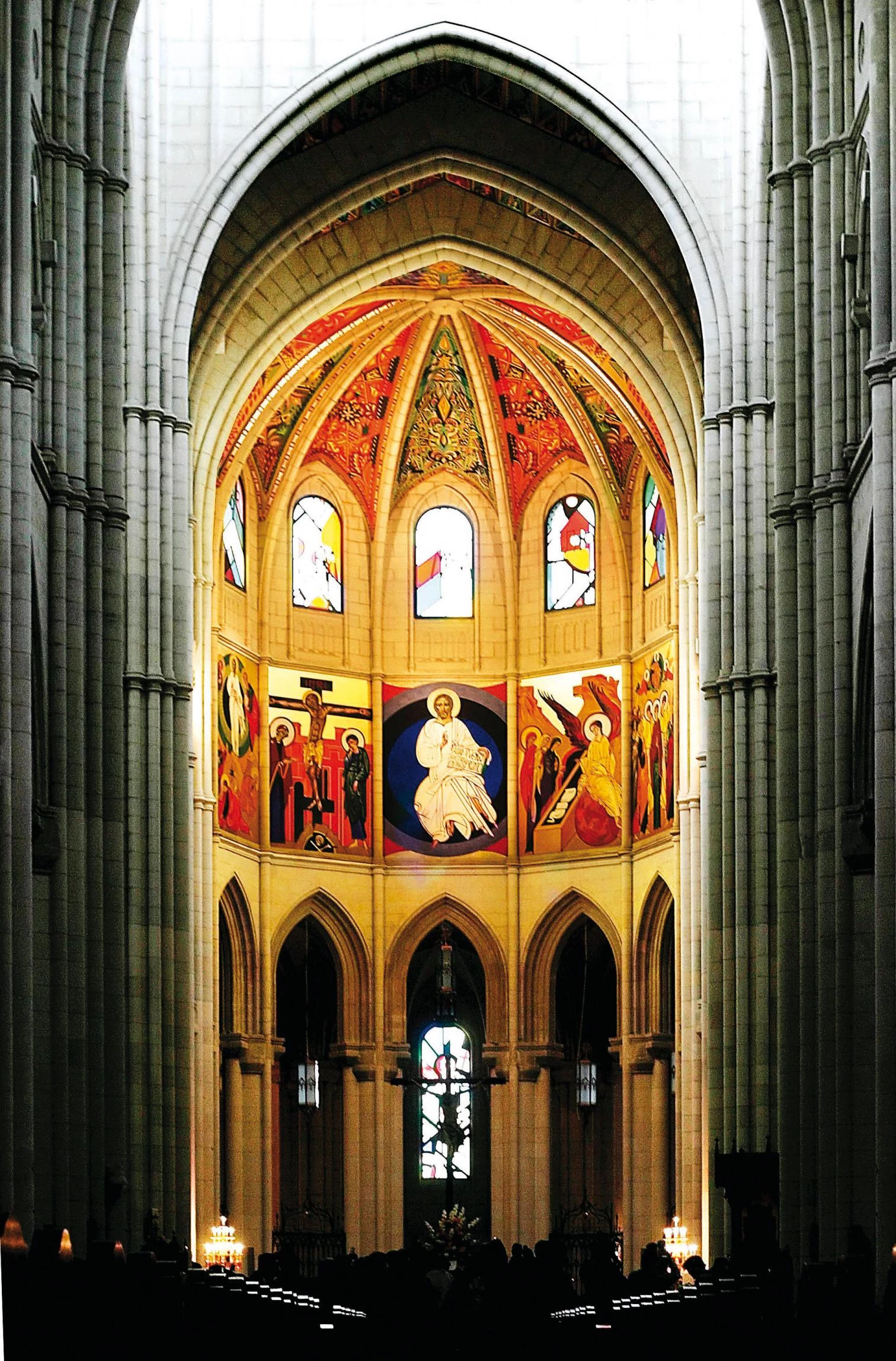

The Monarchy and the Church will survive Kiko Argüello’s frescoes in the Almudena cathedral. At the perspective of the crown prince’s wedding beneath colorful cartoons that feed on icons and codices to manufacture a populist, childish Romanesque, aesthetic fundamentalists murmur philosopher Ortega’s delenda est monarchia; but the monarchy will stand firm against such pictorial onslaught. Cardinal Rouco’s bet, his rushed commissioning of stained glass panes and frescoes to an amateur draftsman, renders him responsible for an artistic crime, but if the Church has not atoned for other offenses, neither will it do so for having ordered schoolwork pictures to grace the apse of Madrid’s cathedral. Like other resilient institutions, Monarchy and Church survive by changing their character while keeping their name, and what subsists is a lexical wrapping for mutating identities, so nobody can be surprised by their aesthetic adaptation to mediatic democracy.

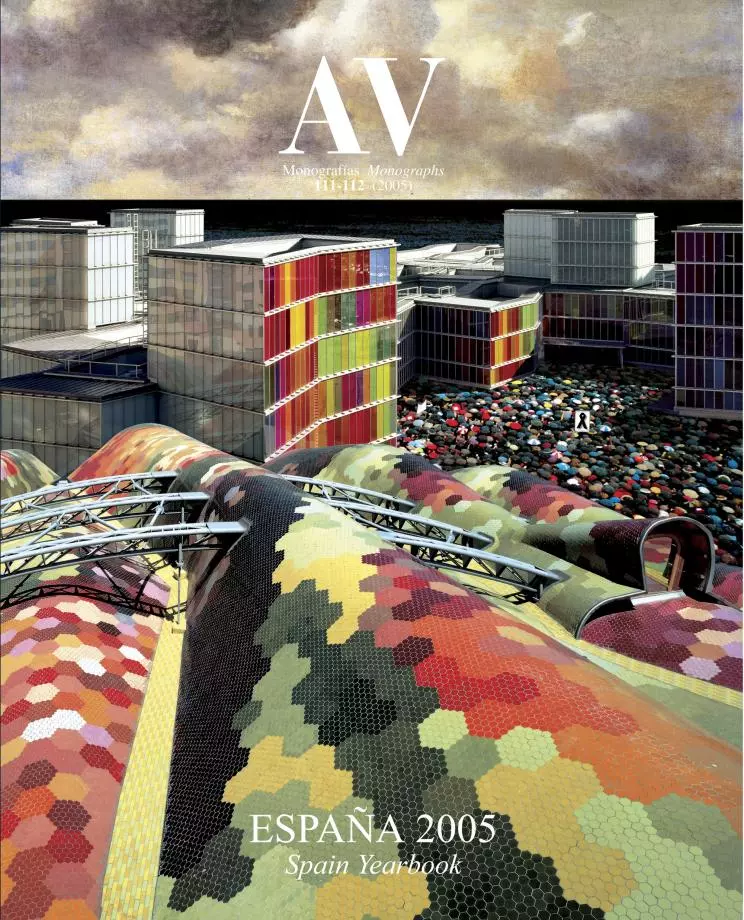

The bourgeois mediocrity of prince Felipe’s new residence contrasts with the solemn architectural scenarios of his wedding, the Royal Palace and the Almudena Cathedral, both in the monumental skyline of Madrid.

If Felipe de Borbón’s monarchy is only nominally heir to that of Philip II or Philip IV – legitimacies and dynastic changes aside –, Rouco’s church is even more removed from Julius II’s. Indeed, it is a long way from the autocratic refinement of the great Habsburg collectors who built El Escorial and put together the canvases of today’s El Prado, to the mesocratic mediocrity of the house of the Prince in La Zarzuela, so easy to mistake for that of an eager nouveau riche. But between the despotic patronage of a papacy that left Michelangelo’s Sistine Chapel or Raphael’s Stanzas in its wake, and the ignorant populism of bishops so pedestrian in their artistic tastes as in their musical preferences, there is an abysmal distance, as can be seen walking through the rooms of contemporary art in the Vatican Museums or attending a guitar-and-choir mass in a peripheral parish.

A royal wedding is not only the union of a couple. It stages the marriage of throne and altar, and its urban ceremonial reinforces their ties to subjects and the faithful, collectives that contemporary democracy prefers to call citizens and spectators. This paroxysm of representation, pure ideology after all, helps one understand the Monarchy and the Church’s current roles as institutions subjected to a regime of opinion not far removed from that governing political organs, and explains their discerning determination to present themselves with the friendly apparel of mass aesthetics. A museum-ripe Pertegaz, an operatic Nacho Cano, and a courtly Pascua Ortega triangulate the artistic terrain of the wedding, and the patrimonial profile of Madrid’s western cornice, with the Royal Palace and the Almudena cathedral engaging in dialogue, supplies the picturesque postcard of a historical fiction and the optimal stage for the solemn pomp of a publicity spectacle serving State and city.

The royal wedding was held in a building criticized for its traditionalism, the Almudena cathedral, but whose historicist architecture has been redeemed by the contrast with the pitiful frescoes and stained glass of the interior.

Turned into a fortress with F-18 combat planes and a NATO Awacs flying overhead, Madrid is a huge television studio set that hopes to carry out the transmission with no other incident than the usual fainting spells among an enthused crowd of extras played by citizens. But on this 22-M, the tragic mark of 11-M is still fresh in our memory, and everyone knows that if battles are fought today in the field of media-reproduced images – as is being shamefully reminded to the occupation army in Iraq –, the concentration of cameras attracts symbolic or physical combatants just like magnets do iron filings. An exceptionally cynical, or especially stupid, guru of communications recently called upon Madrid institutions to capitalize on the mediatic impact of the train bombs to promote the city. We can only hope that the wedding news does not provide more dramatic excuses for city marketing.

The matrimonial event comes at an optimal time both for the Monarchy and the Church, for it produces an opportune mass exposure and administers an efficient injection of media legitimacy to the two troubled houses. The Monarchy, which after Mario Conde and Javier de la Rosa has also seen Manuel Prado go to prison – three staunch supporters and members of its inner circle –, faces a constitutional revision that, initiated to remove discrimination against women in the succession to the Crown, will end up provoking a public debate on the archaic discrimination that favors the position of a particular family at the head of the State – although the foolish awkwardness of the current republicans is indeed a guarantee of continuity. As for the Church, which has managed neither to curb the scandal of pederasty in the clergy nor justify its obstruction of AIDS prevention and stem-cell research, it tries to find support in neo-conservative grassroots movements to oppose the reticence of elites, but it is not easy to set Bad Education against The Passion of Christ: the Almodóvar of Cannes cannot be obscured by the box offices of Mel Gibson.

In the specific realm of architecture, the wedding is serving as a reminder of the builder of the Almudena, the nonagenarian Fernando Chueca Goitia, a great historian whose perhaps inevitably historicist work has always been controversial among his colleagues, but which here crowns the cornice over the river Manzanares with scenographic sensibility, thereby blending into the urban landscape of a populist or neo-traditional postmodernity. In any case the obsolete languages used in the construction of the cathedral have been made good by the subsequent ornamentation of the chapels and the execution of the frescoes and stained glass windows, all so abominable that visual hygiene makes one abstain from commenting on them, and even from going to see them; in this following the example of Aki Kaurismaki on American thrillers, which he reviews without condescending to watch them, or Emilio Lledó on television, whose current reform he spearheads as member of the Spanish ‘wise men’s committee’ without deigning to own a set.

The architect Ignacio Vicens seems to have reached similar conclusions, as he has tried to dignify the deplorable scene of the wedding by hiding the chapels with screens and tapestries of Biblical themes – mythological themes have been used for the courtyard of the Royal Palace, venue of the subsequent banquet – and darkening the stained glass windows, this both to protect the tapestries and deviate attention from the offensive frescoes. Vicens, who combines aesthetic sensibility with liturgical erudition, and who designed the platforms of the last papal visit with minimalist elegance, has on this occasion not been able to complete his ephemeral architectures, thanks to the uncultured obstinacy of Madrid’s archbishopric. Even then, he has successfully come up with a Potemkin set that will delight millions of television viewers, and maybe this will at least spare us Spaniards the embarrassment of seeing ourselves represented before the world by the naïf iconography of a visionary telepreacher.