Classical thought established a seamless transition from the private realm of the house to the public sphere of the city. In a famous text, Leon Battista Alberti assured that the city is a big house, just as the house is a small city, appropriately stressing the correspondence between the whole and the parts that characterizes classicism, and joining the different scales of the environment in a shared worldview. But the Renaissance city is often made up as the private sphere of a prince or a family, and the stately house also has representative and formal functions that belong to the public realm. Humanism, after all, was not based on the autonomy of individuals, and the concept of intimacy or privacy was still far from emerging in social history.

The irruption of individualism does not occur until the Enlightenment, the beginning of a radical transformation of habitation and territory, renewed stages of the autonomous activity of a myriad of elementary particles freed from the links that gave them cohesion while limiting their freedom. Set in motion by this colossal change, the city becomes a new organism, whose accelerated growth brings about what we call the urban revolution: a process driven by individuals, and that however devours them as Saturn his children, so that industrial society everywhere adopts collectivist structures that cause the gigantism and the alienation of the metropolis, the urban malaise that is expressed in the search for personal paradises.

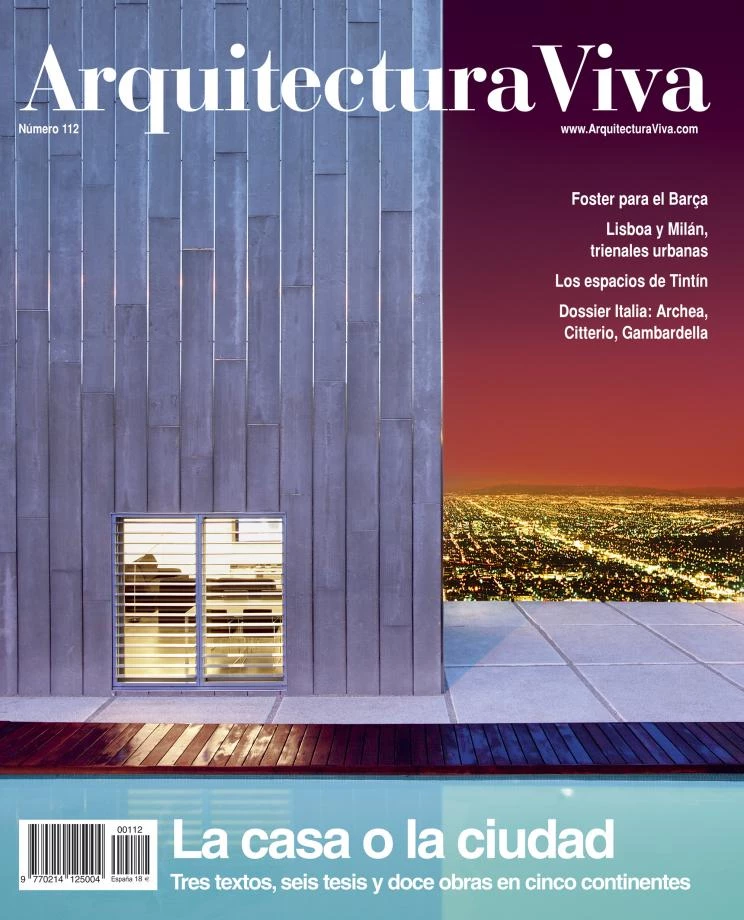

On the threshold of the 21st century, the city is no longer a house we can confidently inhabit, and even less so is the house a city that supplies the essential elements of sociability. One could say that the city has become uninhabitable and the house unsociable, so that the two can only be joined by a disjunctive conjunction: the house or the city, for today’s city has become an enemy of the house, just as the house is at war with the city as it is. In fact, the house – or rather the endless multiplication of individual or single-family homes – has created its own city, a blurred version of the metropolis that the reformers of the 19th century called garden-city, and that today we prefer to qualify as suburban to avoid calling it ‘infraurban’ or ‘antiurban.’

Publishing fine houses without drawing attention to the territorial and social model within which they occur may betray a certain critical blindness, and here there is an effort to make up for that omission through the oxymoronic or schizophrenic mixture of texts that document and appraise urban sprawl along with projects that illustrate the conceptual or formal refinement of some remarkable houses. This combination of abrasive writing and eye candy is disconcerting, and perhaps reprehensible; but the society of spectacle drags us all, and in the troubled waters of this river that carries us along – driven by the current or the wind of history as the angel of Paul Klee under the gaze of Walter Benjamin –maybe we can only hope to keep our eyes wide open.