The Iberian Peninsula is our common home. United by geography and divided by history, Spain and Portugal count three decades of democracy and two in the EU entwining their political paths, linking their economic structures and entangling their social fabric. The domestic intimacy of this shared pentagonal peninsula slowly weaves a network of material and spiritual ties that reinforces the unity of the territory – from river basins to weather reports –, the transport connections and the permanent flow of ideas or emotions between neighboring cultures. But the difference in physical and demographic size between our two countries arouses suspicions that are hard to dispel, rendering turn-of-the century Iberian Federalism an obsolete instrument to guide current processes of integration.

If, as a recent survey shows, 28% of the Portuguese and 46% of the Spaniards favor this political marriage, an even greater number prefers living apart together; if the writer Saramago defends the dissolution of the two states into another one called Iberia, one cannot forget that the appeal comes from a Portuguese married to a Spaniard and settled in the Canary Islands; and if the Portuguese Minister of Public Works, Mario Lino, calls himself a “convinced Iberist”, the assertion is just as significant as the later accusations of disloyalty against the politician. Perhaps Mário Soares is right when he deems it impossible to “build an Iberian Federation”, and we should accept what professor Andrés de Blas calls “weak Iberism”, which promotes relations but not the “strong Iberism” of political union.

Today the interconnection of energy networks and transport infrastructures – aiming to combine the radial system of Spain with Portugal’s axial one, and to build the Madrid-Lisbon high-speed railway –, the mutual penetration of the business organizations – with over a thousand Spanish firms working in Portugal, and 400 Portuguese ones in Spain – and the cross-fertilization of the social and cultural fields – from tourism to language learning – paint a picture of growing integration, spearheaded by banks, utilities and building companies. The latter, spurred by mergers and acquisitions, are establishing a single peninsular market of public works that includes water and railway projects as well as highways and real-estate, in a macroeconomic version of the micro tune of our shared home.

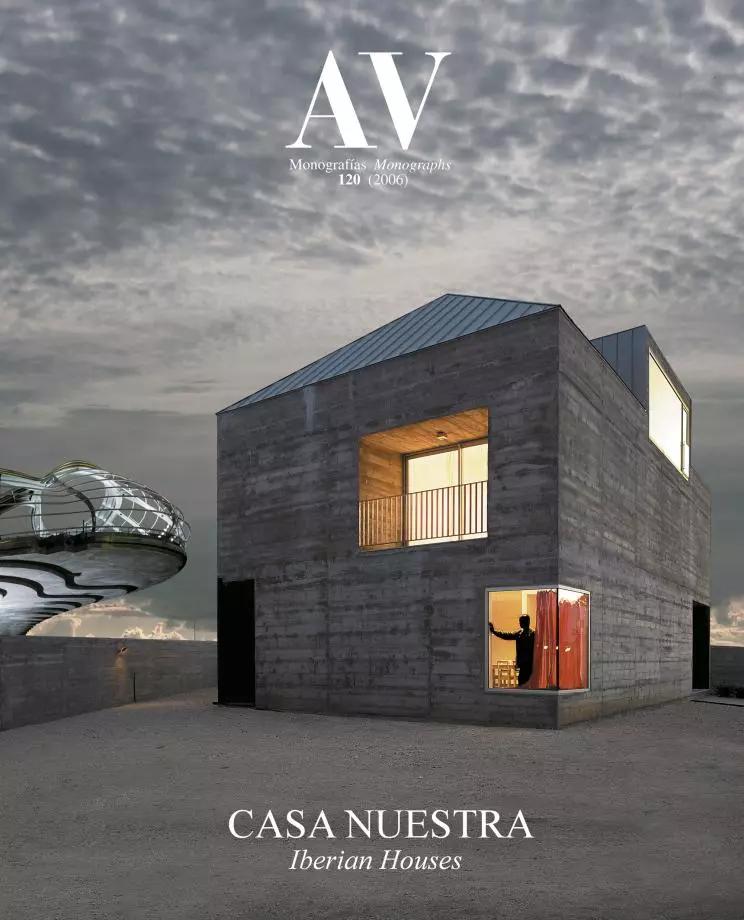

The 24 houses included here, impartially distributed between Spain and Portugal, hope to become a printed metaphor of our common residence, in this peninsular finis terrae of a Europe that remains unsure about its future. Preceded by four artistic investigations on the promises of happiness and the intimate nightmares of the domestic realm – divided with the same symmetry – and followed by three Spanish experiments and a brief essay by the greatest Portuguese architect, these two dozens of Iberian houses offer a nuanced conversation between uses and habits, ideas and attitudes, languages and forms. If we listen carefully, this choral dialogue leaves a residue of substantial agreements and minor differences: perhaps the wickers that serve to weave our everyday life in the shared space of a common house.