The house puts us to the test. If the domestic project is about life, any house makes us choose between effort and routine. In his prologue to Ibn Hazm’s The Ring of the Dove, Ortega y Gasset described the existential ambiguity of the Germanic and Arabic peoples that grafted themselves onto the sclerotic remains of the Roman Empire by explaining how they combined “life as it should be” and “life as usual”: the exemplary character of classical life and the everyday nature of their barbaric life. Camped on the edges of a modernity afflicted with necrosis, architects try to reconcile the ethical and utopian component of the modern house with the choreographic dimension of age-old habits: the rhetorical model of “life as it should be” and the wearied reality of “life as usual.”

Nevertheless, the luminous totalitarianism of modern reason contemplates the house with skepticism. Its individual condition is opposed to the collective logic of the city, and its uniqueness hardly harmonizes with the universality of the modern project. Alejandro de la Sota, whose provincial extremism reflects modern radicality, often said that the project of the house, as a service to a client, is incompatible with the dignity of the architect, who only preserves his integrity if he transforms the commission into an experience. Archaic to the futuristic architect and petit bourgeois to the revolutionary, the house acquires modern legitimacy only if it subverts customary practice – instead of building routine, “how we should build,” and instead of functional routine, “how we should live.”

But we no longer know how we should live, nor whether such a question can still be formulated. Liberal pluralism and social-democratic conformity have reduced life to the private domain, and this to the consumption of ‘lifestyles’. Adorno expressed it well in an aphorism of his Minima moralia: “What to philosophers used to be life, has become the sphere of the private, and afterwards simply one of consumption.” And this, a “caricature of real life,” transforms the quest for a just life into a traurige Wissenschaft – far from the fröhliche Wissenschaft of the Nietzsche who, in asserting his vital autonomy from the domestic yoke, gladly wrote: “I do not own a house.” Nowadays, alas, it is our lives we are not the owners of.

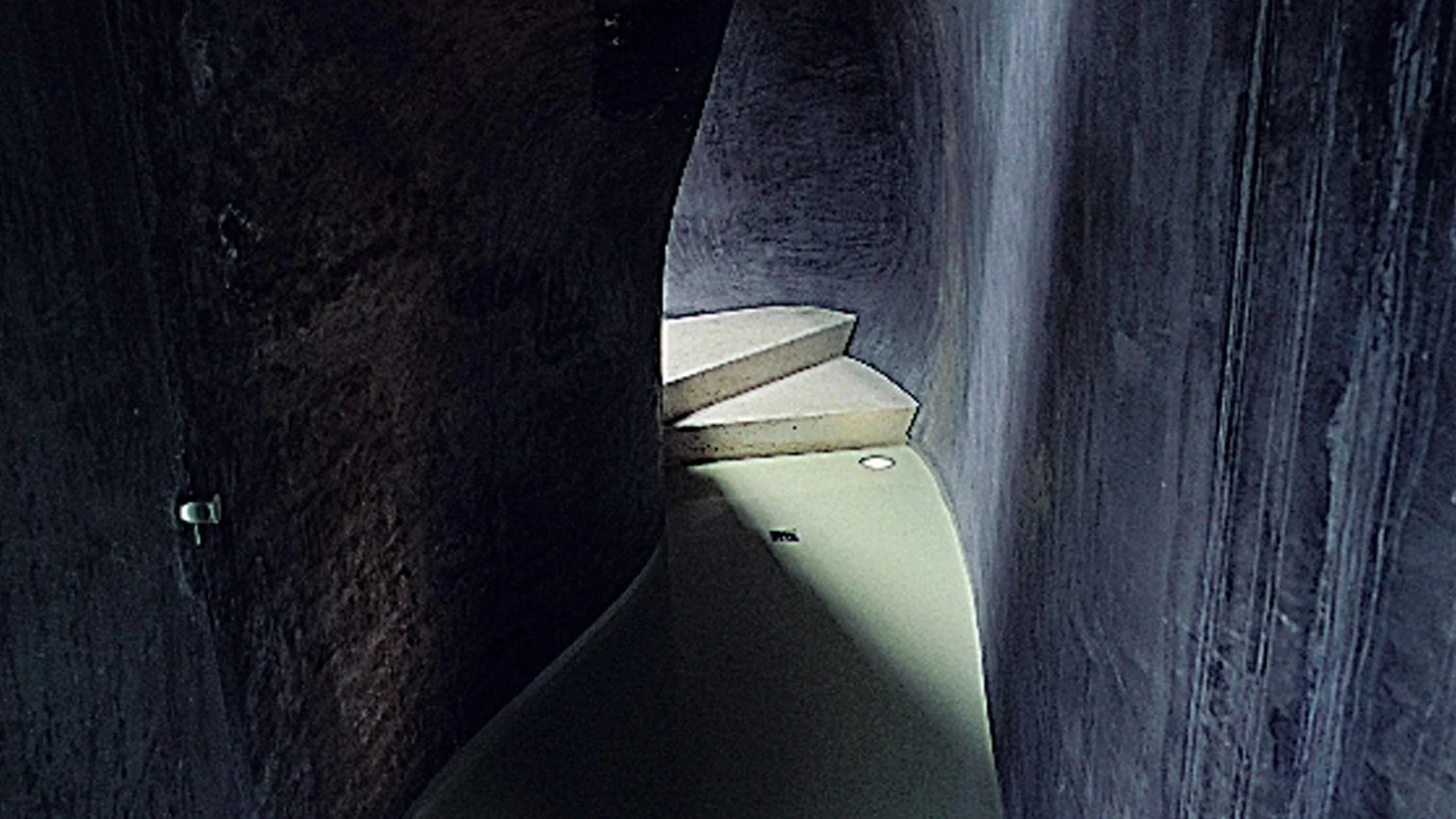

Restricted to the domestic field, life becomes an abridged falsification. Segregated from the urban scene, the life of the house emits a suffocatingly sweet aroma. To build some residences it is necessary to set up intimate relationships: professional services of those who hire themselves for dreaming, like the character of García Márquez. Not surprisingly, the modern dogma seeks more choral dreams in other collective subjects, upholding the order of production over the disorder of demand and desire so that “life as it should be” prevails over “life as usual.” For if the house of life, in the labyrinthian search of Mario Praz, is but a nostalgic container of memory, the life of the house contracts into the melancholic dimension of habit. The house puts us to the test, but to a test we do not know how to pass.