Declaration of Dependence

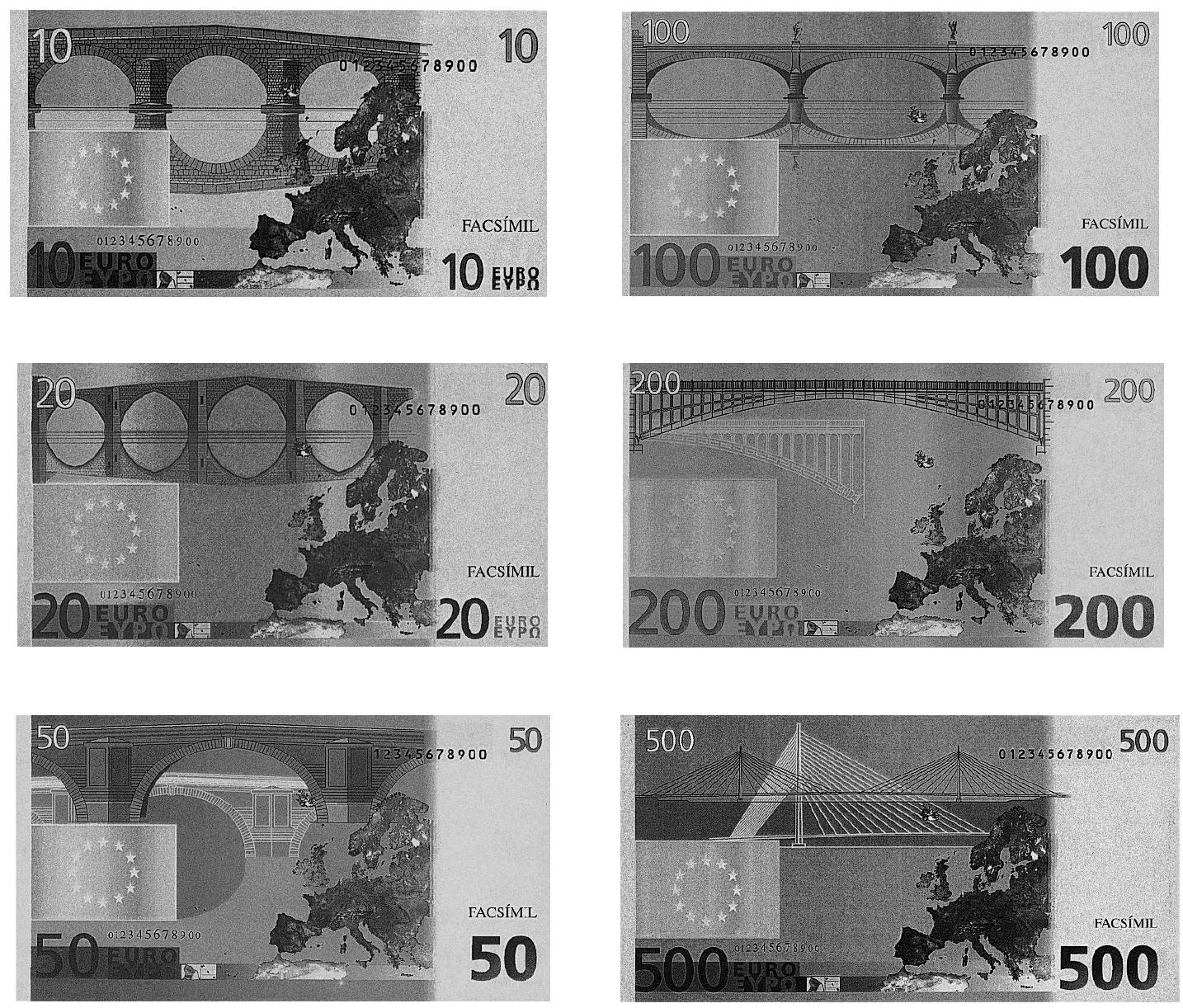

The Monetary Emblems of the New Europe.

The Constitution is a bridge. A festive Puente, long weekend, initiating the Christmas season, and a laboriously elaborated bridge uniting all citizens. As both a feast and a feat, the Spanish Constitution is a political construction that brings to light a social fabric, and its architecture is woven over the warp and the woof of our mutual dependence. The imagery of the bridge as a symbol of communitary cohesion has also been adopted by the European Union, in the euro to be launched on the 1st of January 1999, and there are those who regret that the continent’s political project is not represented more dramatically. Régis Debray has compared the virtual monuments of the euro with the personages and events shown on the American dollar, and voiced his doubts about a European identity that does not pay tribute to the tragic side of history. But both democratic Spain and the European Union are postmodern projects, of variable geometry and imprecise iconography, and the exaltation of heroes of independence gives way to the expression of an interdependence without heroes.

In the paper currency of the United States, the Declaration of Independence is depicted on the reverse of the rather rare two dollar bill, and the obverse portrays its writer, Thomas Jefferson, the most controversial of the nation’s founding fathers. This is the kind of mythical representation Debray expects of a political community. In the case of the United States, it is forced to build upon the symbolic foundations laid by the men who signed the declaration. However, the very contentiousness of its author’s role sheds light on the risks of a project that rests on the compactness of heroes proclaiming a manifest destiny. If Jefferson – incidentally the greatest of neoclassical American architects – was a racist hypocrite, taking one of his slaves as a mistress, and a stubborn defender of French revolutionary terror, the very foundations of the nation are shaky: the architect of Monticello cannot be both a rogue and a nation founder.

As opposed to the heroic iconography of the American dollar, the coins and notes of the euro turn to works of architecture and engineering to symbolize the project of European construction.

The hazy identities of European democracies evidently lack the Homeric dimension that bloody fractures and enlightened heroes provide; but they possess the comfortable nature of conventional construction while avoiding, in their changeable consensi, the mythical crystallization of a hall of heroes. The use of works of architecture in the euro bills perfectly symbolizes the chorally deliberated condition of the Europe that Spain subsumes itself in, renouncing the rhetorical fiction of a sovereignty that has dissolved in a global interdependence, and contrasting significantly with the determination of some Catalan and Basque politicians to give their communities an epic history.

The liturgical celebrations of Spanish centenaries this year have shown significant emotional temperance. Lorca has not been championed by homosexual or leftist groups, but presented as a luminous poet who merges racial with cosmopolitan themes, of vernacular roots and avant-garde fruits. The episode of ‘98 has not been carped as a military, political and psychological catastrophe, but used as a pretext for exhibitions on turn-of-the-century painting. And Philip II has neither appeared as the black spider who wove the bureaucratic web of his empire from El Escorial nor as the prudent king who wisely administered a Spain where the sun never set, but as a cultured prince and lover of life, a refined collector and meticulous governor. The selfcomplacent tepidness of the centennials reflects a generally acritical panorama, and such absence of passion is reassuring to those who fear the stirring up of the beast that has slept for two decades to the mesmerizing tune of the democratic constitution.

There is no place for heroes and saints in the elaborate triviality of Spanish and European democracy. “No founding event, no grand designs, no baptisms of fire,” as Debray laments. But for the story of independence to assume dramatic plausibility, heroes need tyrants. The neurotic ant Z, whom Woody Allen gives voice to in the DreamWorks production, would not have become the liberator of his community of hymenopterans had he not dreamt of an insectopia, but neither would he have had it not been for the treacherous Mandible. The virtual architectures of the anthill were designed in animation computers and inspired by the works of Gaudí, an enlightened builder on the way up to the altars. Fortunately perhaps, we do not need such dramatic sacred forms to erect the customary and consensual architecture of a habitable Europe and a habitual Spain. The festive occasion of Constitution weekend, without pompous political metaphors, encourages us to enjoy the last tepid drops of autumn honey. It is of this sweet and ephemeral substance that civil coexistence is made.