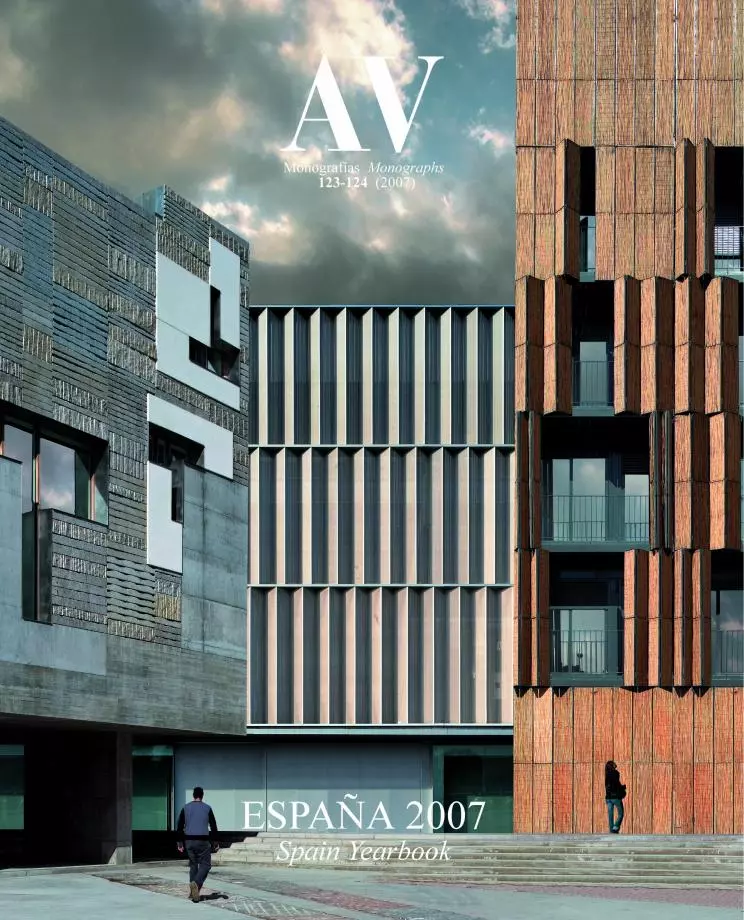

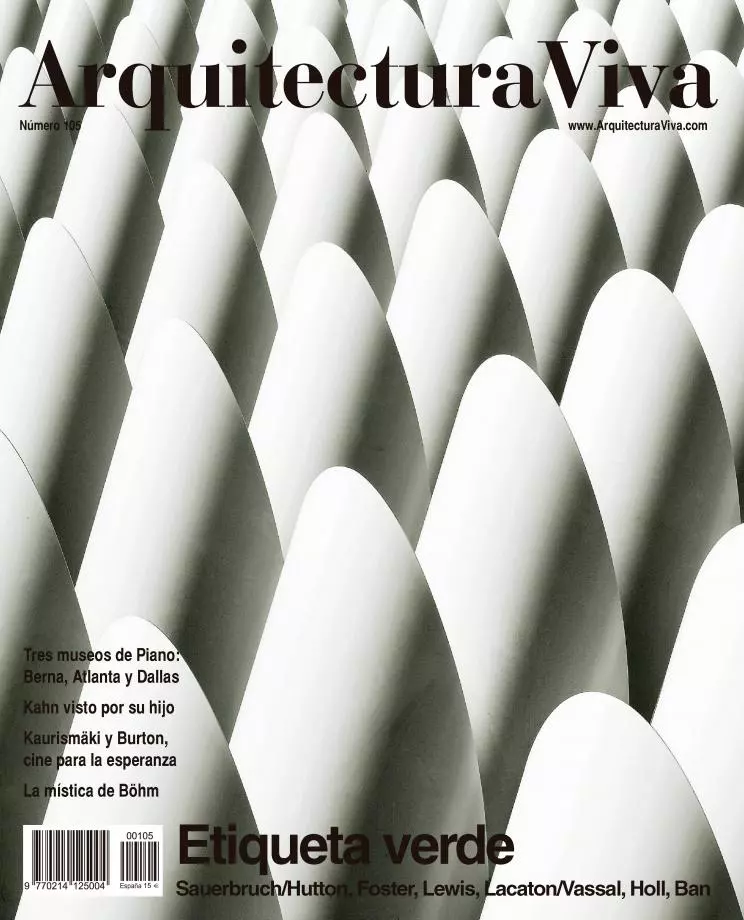

Spanish Landscapes

The Marbella crisis has put urbanism at the center of the political debate in Spain, a country that seems doomed to choose between prosperity and landscape.

Marbella has undergone an exorcism. With Mthe dissolution of the City Council and the imprisonment of those responsible, political and judicial Spain tries to drive away the all too familiar demons of speculation and corruption, expel the evil spirits of the healthy body of a young democracy. But Marbella is really the extreme case of a common disease: the penal pathology may reach its worst there, but the symptoms are everywhere. As much the coasts as the edges of cities, and even rural areas that up to now have been intact, are suffering a historic mutation driven by the economic boom and the new demands that come with it. Because of the pain we feel at the thought of the accelerated disappearance of natural landscapes, we tend to describe this process of colonization in medical terms like infection or metastasis. But this impetuous growth can also be interpreted as a result of the vitality of a prosperous and hedonist society that multiplies its needs and desires with impulsive impa-tience. The territory is always a physical picture of the culture that has molded it and, whether we like it or not, Spain’s new landscapes accurately reflect what we are today: well-off, smug and vulgar.

The uncontainable advance of asphalt, just like the real estate bubble itself, is not only a product of corruption or greed. It comes from a social demand for first and second homes that low interest rates and lifelong mortgages have made financially accessible, and that unanimous motorization and the new transport infrastructures have made geographically accessible. In the nineties, urbanized land in Spain increased by 25% (a good 50% in Madrid or on the coast of Valencia and Murcia). Everywhere, this spread of cement and brick arous-es the same contradictory reaction: on one hand, despair at the destruction of the environment; on the other, frenzied acquisition of seaside apartments or houses in the low-density developments of urban peripheries. The town planner Ramón López de Lucio recently took the trouble of documenting the new residential landscapes in the outskirts of Madrid, and the result was as depressing as it was stimulating. To begin with, the low density of this urban environment pushes all activity to the large commercial centers that serve to finance the costs of urbanization, but privatize the collective domain and leave residual public spaces exposed to vandalism. But at the same time, the conventional developments of row houses or low-rise blocks of apartments that form the greater part of the new compounds are uniformly spacious and functional in design, and carried out with a very reasonable degree of material quality. They are homogeneous in their lifeless, selfwithdrawn triviality, yet solid, well-equipped and luminous.

The surge of Marbella, symbol of a Costa del Sol whose uncontrolled urban growth is reflected by the panoramic view of Mijas, was based on corrupt political practices that led to the dissolution of the City Council by the courts.

Those of us who write in newspapers are in general too old and too elitist to understand that the indifferent anomy of these new urban landscapes do not make them any less desirable, that their abysmal visual mediocrity does not in any way decrease their market value, and that the absence of collective activity in them is not as important to the home buyer as the quality of window frames or the tiling of floors. Urban life has been replaced by suburban life, a way of occupying space and time that also characterizes all the recent developments on the coasts. These new forms of relating to one another and consuming are for many an additional attraction. Never mind if there is no street life; there will be life in a commercial center, around a community swimming pool, or in a backyard barbecue party.

Millions of Spaniards have with their mortgages voted for the faded suburbanity of the peripheries and for the massive vacational colonization of the coastline. Both are expressions of economic prosperity, but also of a political democracy that gives governing capacity to municipalities that are powerless in the face of the colossal forces that shape the territory. They may be routinely greedy and occasionally corrupt, but these forces feed on the freedom to choose of real estate buyers, and the landscapes they have shaped faithfully portray the Spanish society of democracy. Moreover, they are electorally devastating, as we have seen in the caricatural case of the Costa del Sol, but also as we witnessed when Britain’s New Labour was forced to shelf the Urban White Paper drawn up by Lord Rogers, which included a call to refrain from building on ‘greenfields’(previously undeveloped land), a recommendation that would have antagonized the rising middle classes of the cottage and the SUV that currently make up the demographic and electoral support of any European political center.

The outcrop of cranes amid the endless rows of houses in Paracuellos and the massive residential blocks of Seseña, both near Madrid, contrast sharply with the essential landscape of Lalín’s carballeira, in Galicia.

In a recent exhibition in Madrid’s Círculo de Bellas Artes, the architect César Portela showed his interventions in two Galician landscapes of singular beauty and emotion, the carballeira of Lalín and the isles of San Simón and San Antonio in the estu-ary of Vigo, two intact natural places which tourist and holiday bulimia has not yet devoured with its unstoppable machinery, and the exhibition’s timing with the Marbella crisis made one contemplate the contrast between the way we were and the way we are. The carballeira, a spot in the woods presided by a monumental granite table where 150 neigh-bors come together for communal celebrations, is a space of archaic poetry that evokes the popular fiesta and the sacred mystery, but also speaks of the frozen time of the village and the stifling rigidity of superstition and habit. The isles of the estuary, the location of an old lazar house and jail, stand out for their melancholic nature and the romantic splendor of their essential constructions, but in this lost world of ashlars and lichens that the architect barely touches with accents of glass, beats an ominous past of illness, punishment and isolation. In contrast with the trivial, ostentatious landscapes of Marbella, the aching beauty of these faded places beckons to us with the magnetic force of the abyss of time. But if we look straight and without the moist veil of aesthetic emotion, we will realize that the new landscapes of narcissist prosperity portray us more accurately than those exact traces of the past, which are preserved only like insects in amber. Hypocritical reader, Marbella is all of us.

Carballeira de Lalín, de César Portela