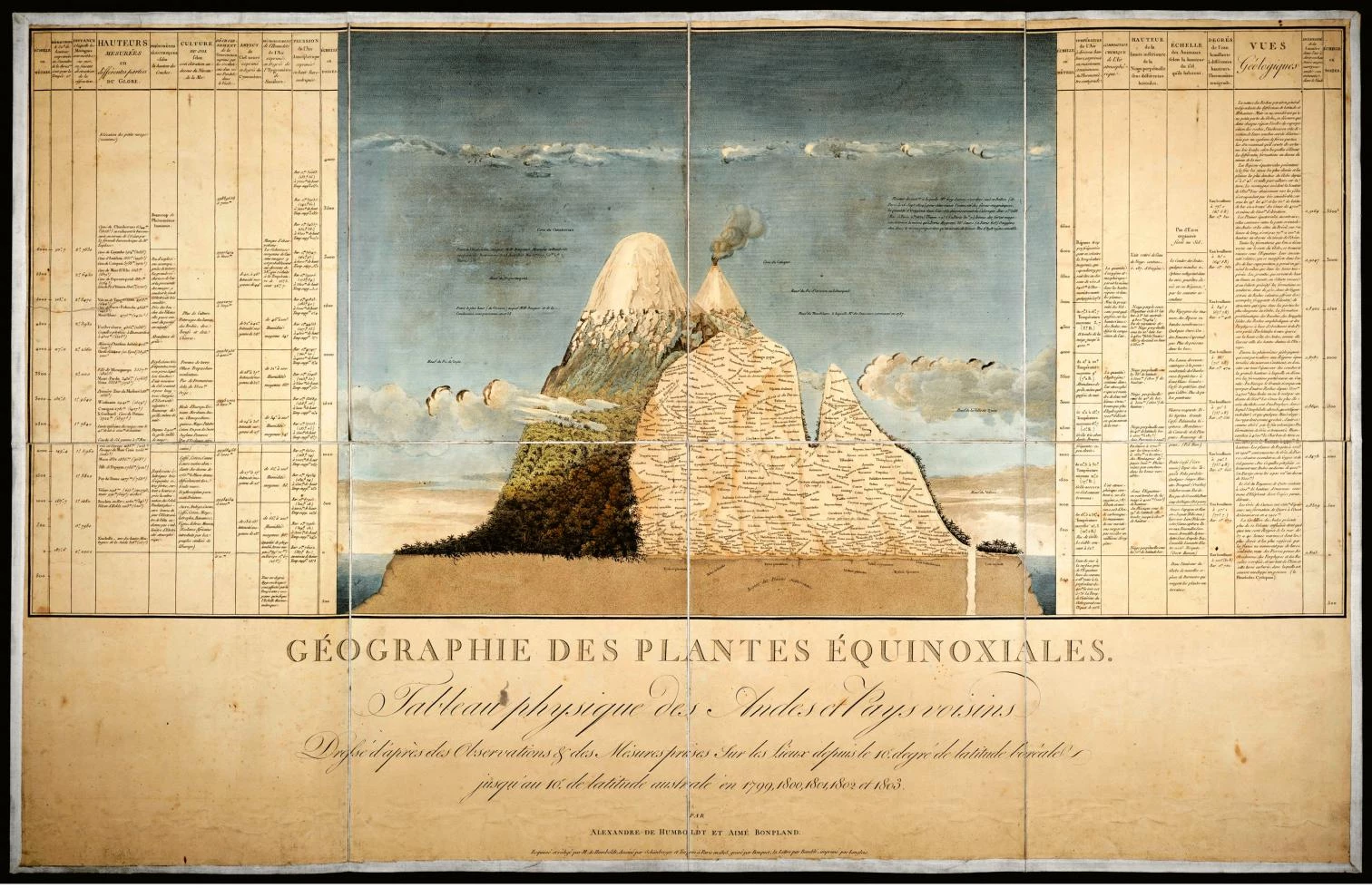

We are all children of Humboldt, but Sandra Barclay and Jean-Pierre Crousse have made special merits to be worthy of that title. The great German naturalist and geographer crossed the Atlantic to explore Spanish America between 1799 and 1804, and upon returning settled in Paris, where until 1827 he organized and published in 33 volumes what he had collected during his journey. The Peruvian architects, after graduating in Lima, made the reverse trip two centuries later, establishing themselves in Paris to take in all that the Old Continent could offer, and went back to their home country to materialize in buildings the fruits of their transatlantic experience. Somehow, their fascination with the tropics, which they discovered with new eyes when back from Europe, evokes the inquisitive gaze of the explorer, and their emphasis on territory and climate as defining elements of architecture reminds of the holistic vision of the scientist who conceived his Naturgemälde, the representation of the unity of nature, in his ascent to the Andes peaks.

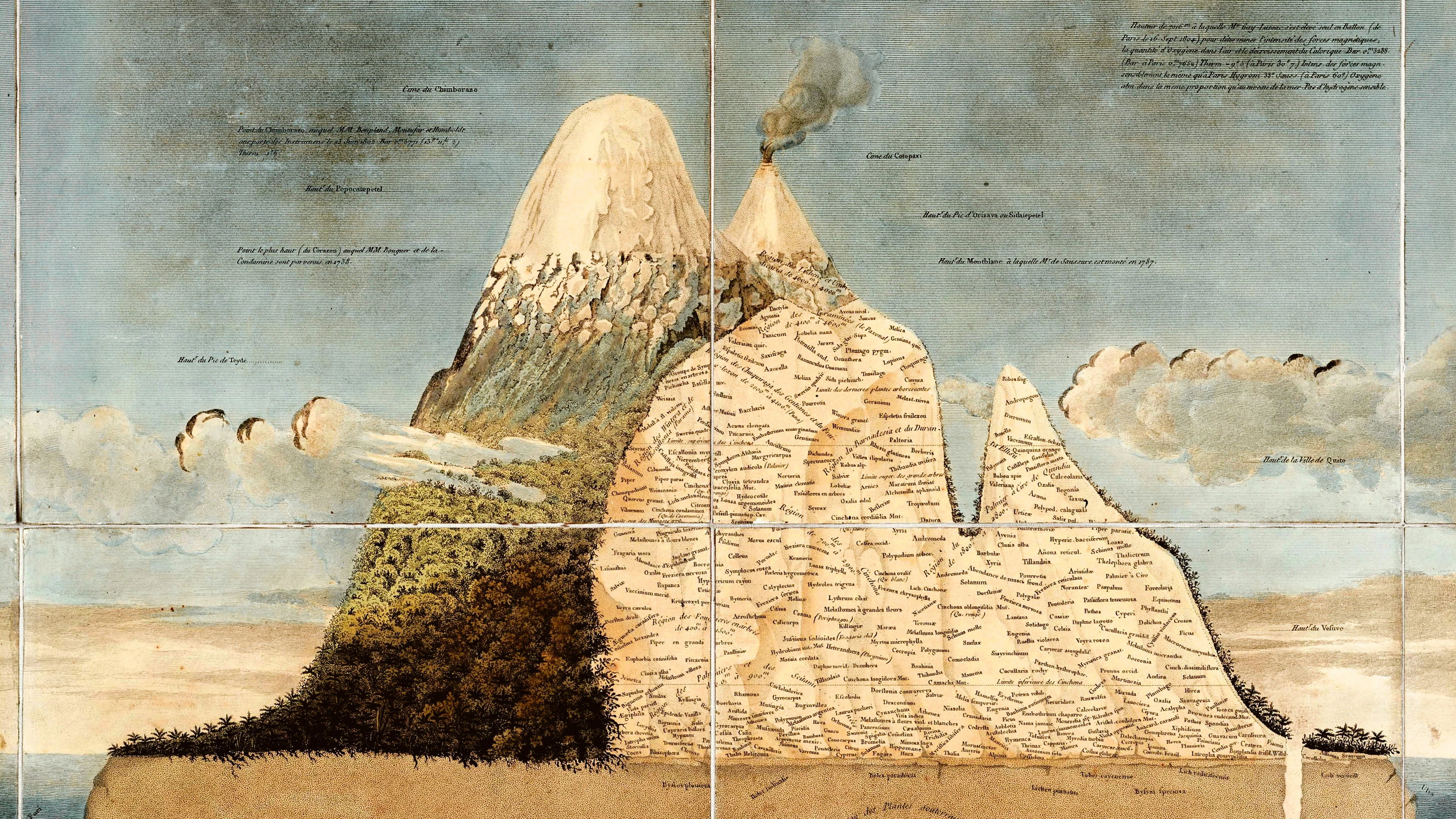

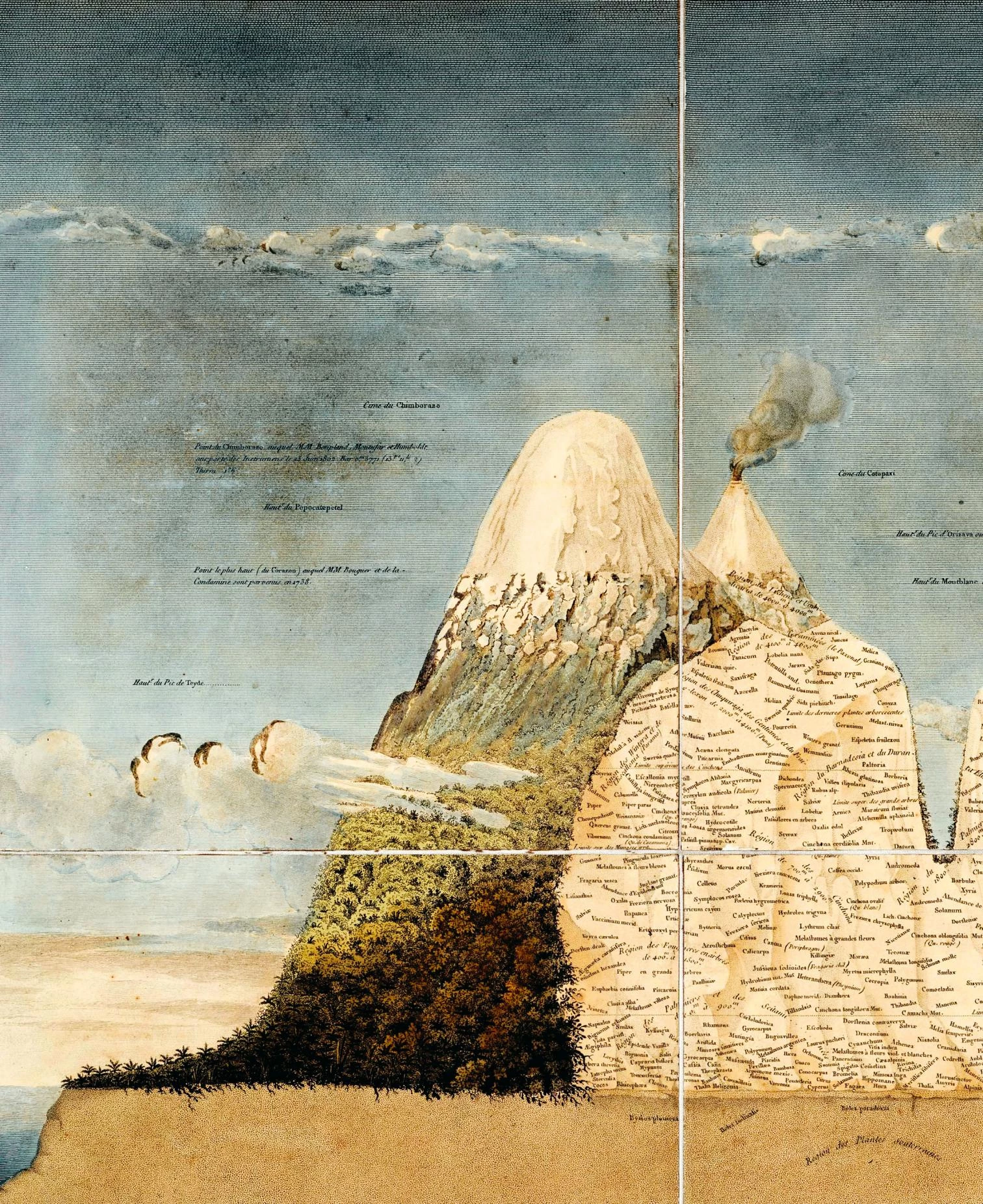

If Petrarch’s ascent of Mont Ventoux in 1336 is a milestone in the aesthetic perception of the landscape, Alexander von Humboldt’s climb of Chimborazo volcano in 1802 marks the crucial moment in what his biographer Andrea Wulf calls The Invention of Nature, seeing it as a web of life woven by ‘a thousand threads,’ connecting his experiences in the Alps, the Pyrenees or the Teide with what was found in the botanic expedition that took him from the Pacific coast to the snows of the Chimborazo. It was ‘a microcosm in one page,’ that the scientist summed up with the extraordinary drawing of the volcano’s cross section. “One single life – writes Wulf – had been poured over stones, plants, animals and humankind,” and this vision, which announces today’s ecological perception of the planet (nuanced by Maren Meinhardt, who underlines its enlightened origins and its ties with German Romanticism), is what has also inspired the recent novel by the Colombian William Ospina on Humboldt’s expedition, Pondré mi oído en la piedra hasta que hable.

Barclay and Crousse put their ears on the stone until it speaks, and the result is an oeuvre of material density, climatic intelligence, and poetic breath that extends along the length of the country, and where each work emerges from the interpretation of landscape, to create microcosms defined by section rather than by plan. From their studio in what Patricia Ciriani has called Lima la sublime – a city that was however described by Sebastián Salazar Bondy as ‘Lima la horrible’ –, the architects assume the imperfections and precariousness of the professional and social environment to raise architectures that ‘worship the Earth’ and possess ‘the deep sense of what remains.’ Ospina’s book opens with a quote from Hölderlin’s Patmos, and perhaps no other can serve best to close the presentation of the work of these two children of Humboldt: “Wir haben gedienet der Mutter Erd’/Und haben jüngst dem Sonnenlichte gedient,/Unwissend, der Vater aber liebt,/Der über allen waltet,/Am meisten, daß gepfleget werde/Der feste Buchstab, und Bestehendes gut/Gedeutet.”