At the Service of Life

Architectural modernity was born at the service of life, but ended up becoming only a visual language. Anne Lacaton and Jean-Philippe Vassal recover the ethical fiber of the modern project to again place construction at the service of the everyday, and their aesthetic emerges without stylistic mediations from their commitment to the comfortable shelter of the organic. Using elements and systems that come from agricultural construction or civil engineering, the architects propose strategies that allocate the budget available with exemplary pragmatism, intelligently establishing priorities to attain results that are both appealing and self-evident. This radical realism fertilizes industry with craftsmanship, research with casualness, and the readymade with bricolage, and the results of this essential mix are inhabitable spaces that harbor both intimacy and sociability, exact works that bring together generosity and joy.

With its bold foundations, the vital architecture of Lacaton & Vassal shows a spontaneous freshness that does not exclude historical referents, from Mies van der Rohe, Richard Neutra or their compatriot Jean Prouvé to the Californian case-study houses of the Eames, Craig Ellwood or Pierre Koenig; and going back in time, it is not difficult to locate a heroic antecedent of their inhabited greenhouses in the Crystal Palace of the gardener Joseph Paxton. But from our own observatory, many will find in this oeuvre confirmation of the theses of past professors of the Madrid School of Architecture like José Fonseca (‘in housing, the floor area is more important than the finishes’) or Fernando Ramón (‘thermal confort needs the user’s participation’), as well as of the laconic diagnoses of masters like Alejandro de la Sota (‘not making Architecture is a path to making it’) or Miguel Fisac (‘my best works are those I did not do’).

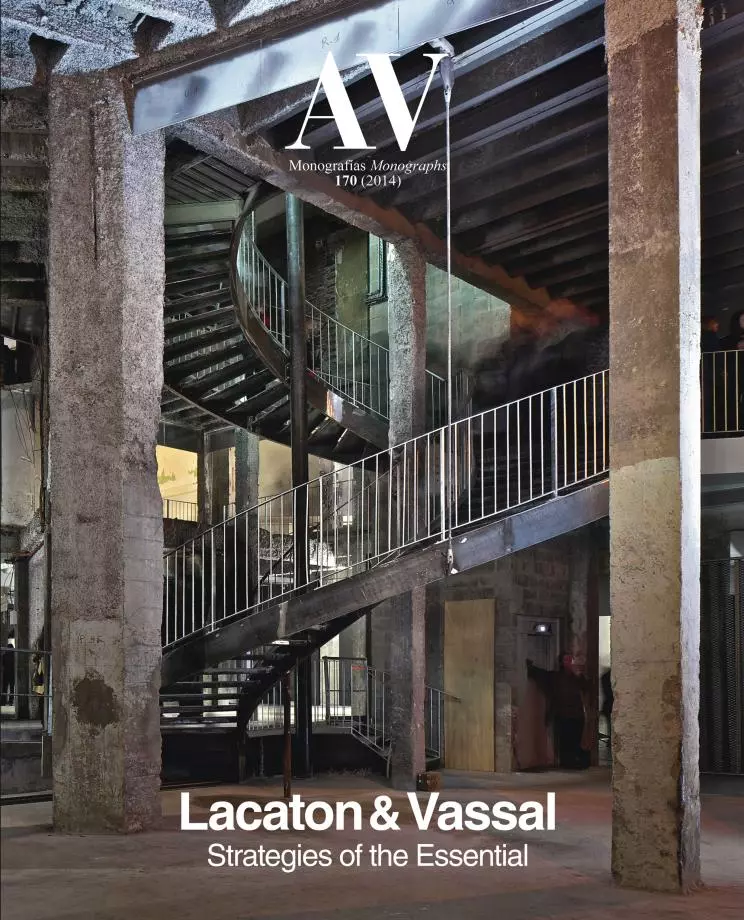

If at the Maravillas ‘no one misses the Architecture it does not have,’ the same happens at the Latapie House, the Nantes Architecture School or the FRAC in Dunkerque; and if Fisac valued highly the works he had chosen not to do because they were unnecessary, something similar applies to the minimal intervention at the Palais de Tokyo, the alternative to demolition at Bois-le-Prêtre or the decision to not remodel the Léon Aucoc Square in Bordeaux because it already possessed ‘the beauty of what is evident, necessary and sufficient.’ That beauty of the necessary can be found in the pavilions, hangars or flower-filled greenhouses by the French architects, and was also in their opera prima, the straw matting hut in Niamey that Jean-Philippe left to return to Europe in 1985: this magazine was born that same year, and celebrates now its thirtieth anniversary and the beginning of a new period with this recognition of an architecture at the service of life.