Deconstruction in memoriam

Jacques Derrida’s death symbolically wraps up an aesthetic movement that claimed to be derived from his thought, and that found in Eisenman its interpreter.

Architectural deconstruction was formulated in opposition to the postmodern style. Ironically, literary and philosophical deconstruction were unequivocal manifestations of postmodernity. This is only one of many misunderstandings that blur the lines of the aesthetic movement inspired by the recently deceased Jacques Derrida. None as flagrant, of course, as the difficult agreement between construction and its reverse, making architectural deconstruction an oxymoron whose terminological contrary has more lyrical than pragmatic validity. But no less significant is the inscrutability of many of the protagonists of this cross fertilization of philosophy and the arts, starting with Derrida himself and deconstruction’s main architectural spokes-man, Peter Eisenman. The Frenchman and the New Yorker engaged in a dialogue of fuzzy outlines and typographic subversions that supplied textual metaphors of dislocation without offering reliable cartographies of shared territories.

Eisenman, who designed with Derrida a project for La Villette, has finished in Berlin a Jewish memorial.

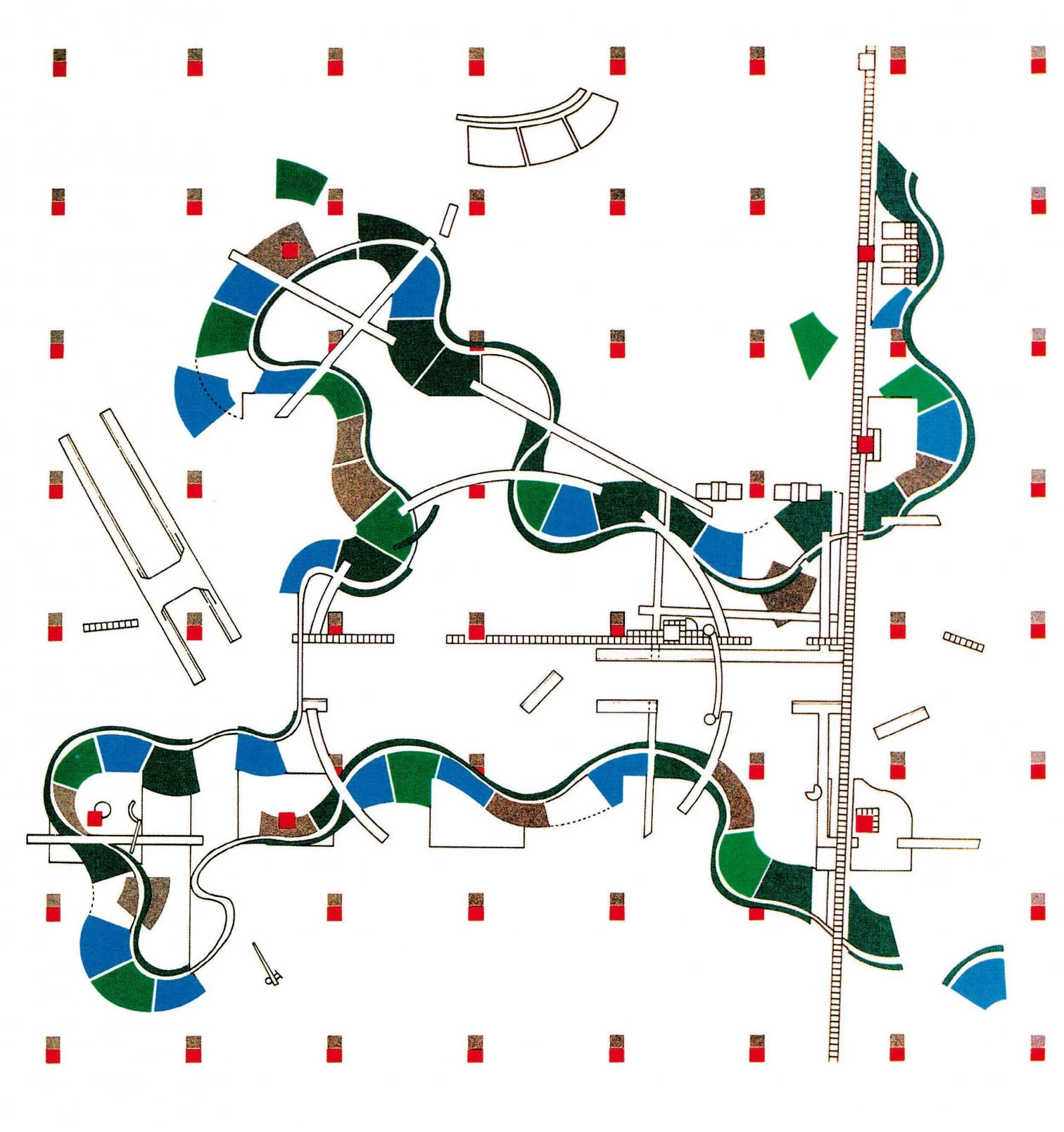

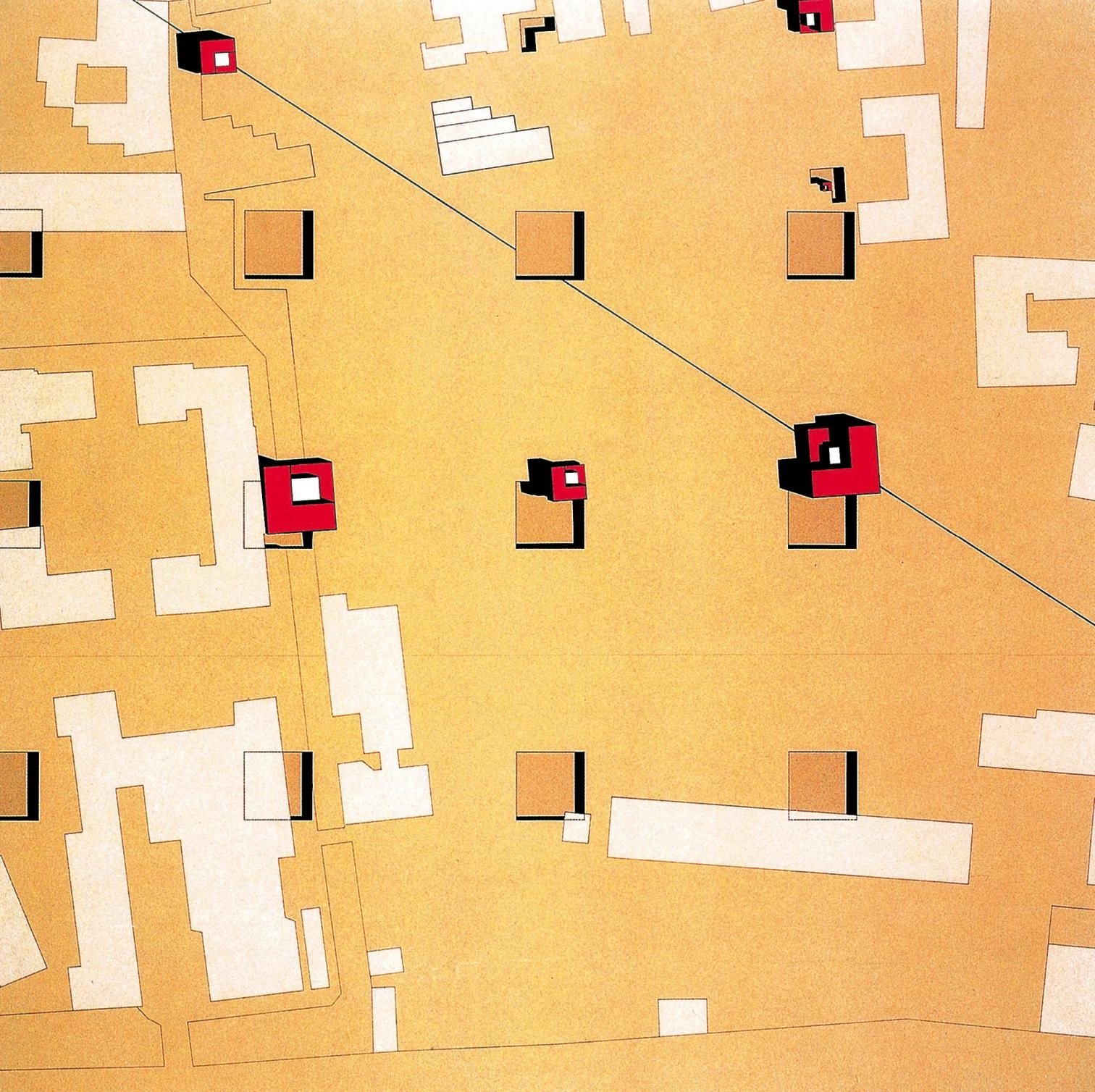

The philosopher of Sephardic origins had become a star of American campuses as early as 1966, when a symposium in Johns Hopkins University introduced his ideas in the United States, but contact with the Jewish architect and intellectual did not come about until 1985, when Bernard Tschumi invited them to team up and design a folie in La Villette. Over a brilliant proposal submitted by Rem Koolhaas that introduced the concept of functional bands, the Swiss architect Tschumi had just won the competition for the Parisian park by proposing a grid of knots (the so-called folies) that evoked a project Eisenman had previously drawn up for Venice’s Cannaregio, which in turn was inspired by a Venetian hospital of Le Corbusier that was never built. The folie never materialized, but engendered a book whose title – Chora(l) Works – alluded as much to the collaboration between Derrida and Eisenman as to the platonic term that had served as a hinge for their dialogue; a text by Derrida – ‘Why Peter Eisenman writes such good books’ – that only critics like Jeff Kipnis considered ironical; and a fervor for architectural deconstruction that was to crystallize in the 1988 exhibition of New York’s Museum of Modern Art.

Organized by Philip Johnson and Mark Wigley, the show brought together the work of seven architects – Eisenman, Tschumi, Koolhaas, Gehry, Libeskind, Coop Himmelbau, and Zaha Hadid – who shared a penchant for disconnected or fragmented forms and were critical of the friendly figuration of the postmodern classicism then in vogue. The title, “Deconstructivist Architecture,” was an allusion to the early 20th-century Russian avant-gardes so admired by many of the architects on display. It was perhaps also a way of distancing itself from the literary deconstruction then dominating the American academe, shaken the year before by the disclosure of anti-Semitic early writings of Paul de Man, the high priest of that school in its Vatican, Yale. As much in this case as in that referring to the Nazi past of Heidegger, and though expelled from school at the age of twelve by the Vichy government’s racial laws, Derrida defended his masters with tortuous arguments that earned him the sarcastic censure of The New York Review of Books: “Deconstruction means never having to say you’re sorry.”

Derrida’s misunderstanding by a part of Anglo-Saxon culture, which culminated in the cause célèbre of the controversial honoris causa doctorate bestowed on him by Cambridge in 1992 – put to the vote for the first time in thirty years, and finally approved by a count of 336-204 – has continued even in death. The front page of The New York Times announced his passing with a headline calling him an “abstruse theorist,” a posthumous attack that has sparked a flood of letters of protest and articles of apology. In one of them, published in the opinion section of the same newspaper, the Columbia University professor of architecture and religion Mark Taylor declares Derrida to be one of the 20th century’s three leading thinkers (alongside Wittgenstein and Heidegger), assesses the final phase of his career, in which his philosophical and literary interests shifted to the spheres of ethics and politics, and evokes his exceptional intellectual generosity and cult of friendship: an affectionate tribute much in line with the French unanimity in positively appraising Derrida – from the special supplement of Le Monde or the wide coverage of Libération to Le Figaro’s respectful treatment – and in contrast to the caustic farewells of journals like The Economist, which in view of theologians’ growing interest in his texts hopes that God will help them to understand him.

Such persistent hostility affected Derrida more than one would imagine. I was privileged to have a regular correspondence with him over the last seven years of his life, and that concern of his never failed to surface in his letters, provoked by the critical texts of The Times Literary Supplement that I would send to him. Already in 1997 he wrote: “Je ne sais pas si je m’habituerai jamais à tant de bêtisse et à tant de haine. Peut-être que ce que je crains le plus, c’est justement une certain habitude. La leur et la mienne.” But those articles, he would write years later, “me sont aussi précieux par le contenu que vous savez (qui m’apprend beaucoup, m’enrage parfois, me fait le plus souvent rire d’un rire résigné) que par le lien amical et durable, la complicité aussi qu’ils entretiennent entre nous.” As many were able to verify, the author of Politics of Friendship practiced it in the fertile form of open dialogue and intellectual accessibility. Like his architectural alter ego Peter Eisenman, the philosopher raised a barrier of textual cryptography that only mercurial conversation and hypnotic reflection could break down.

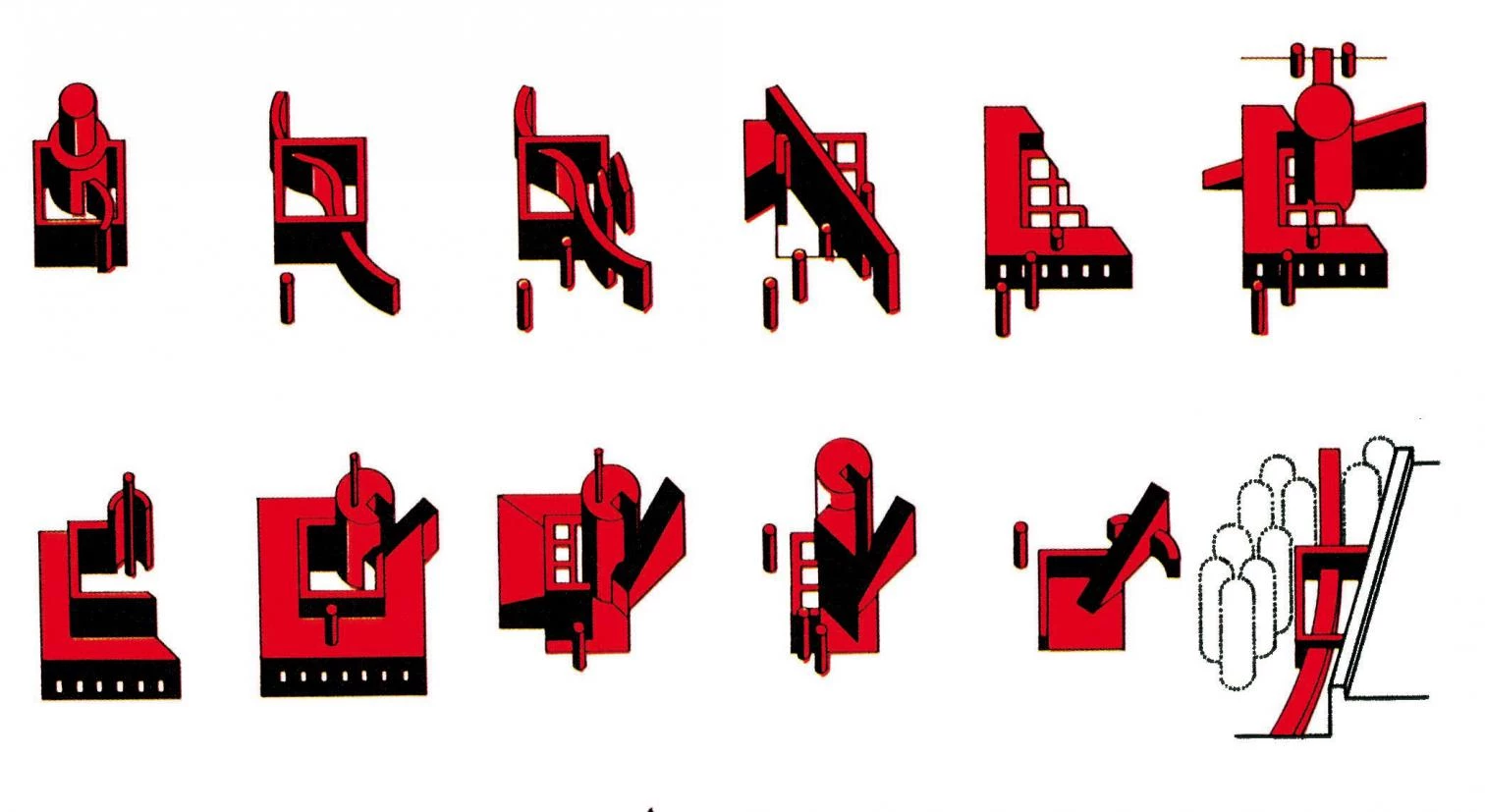

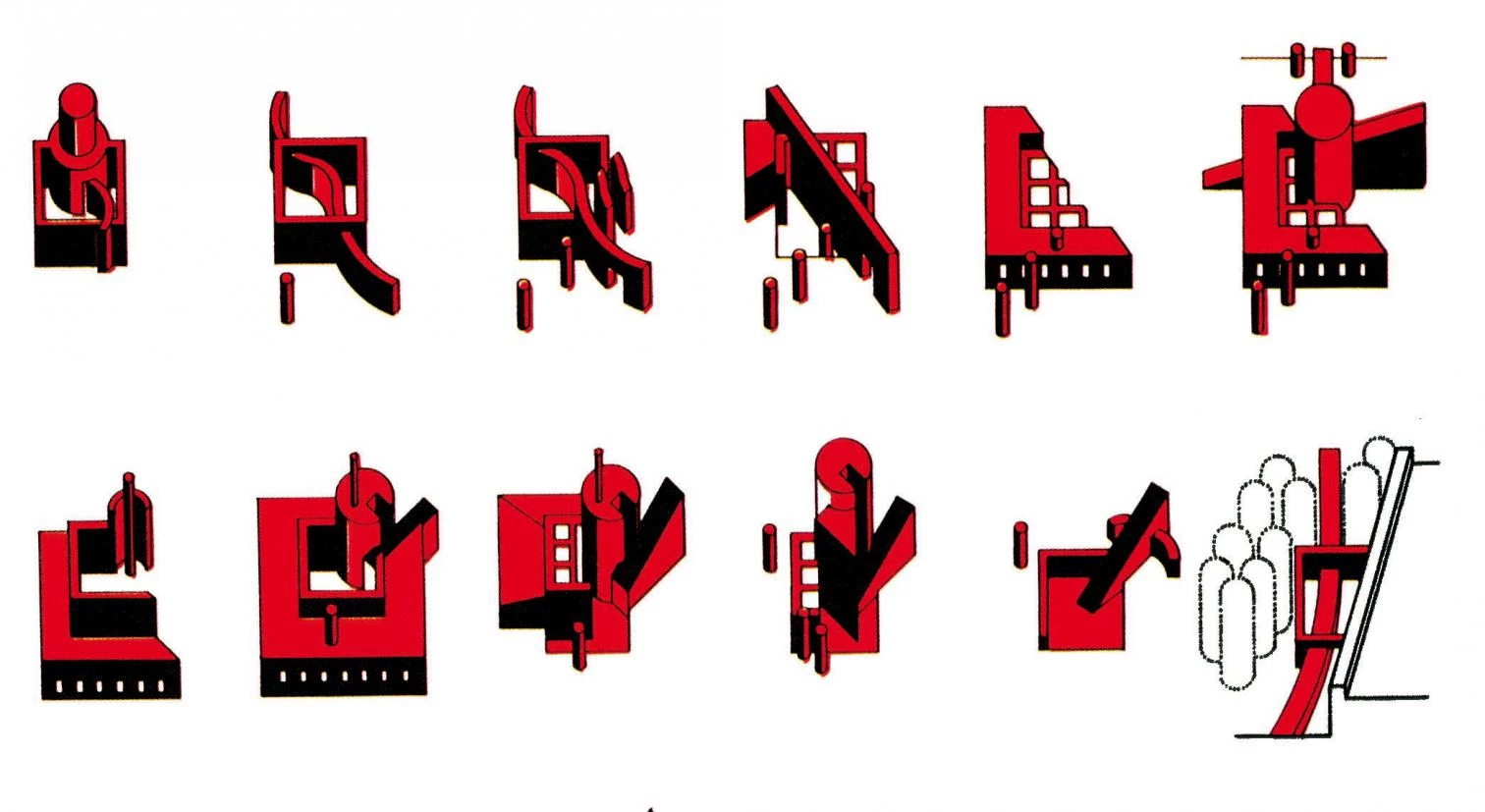

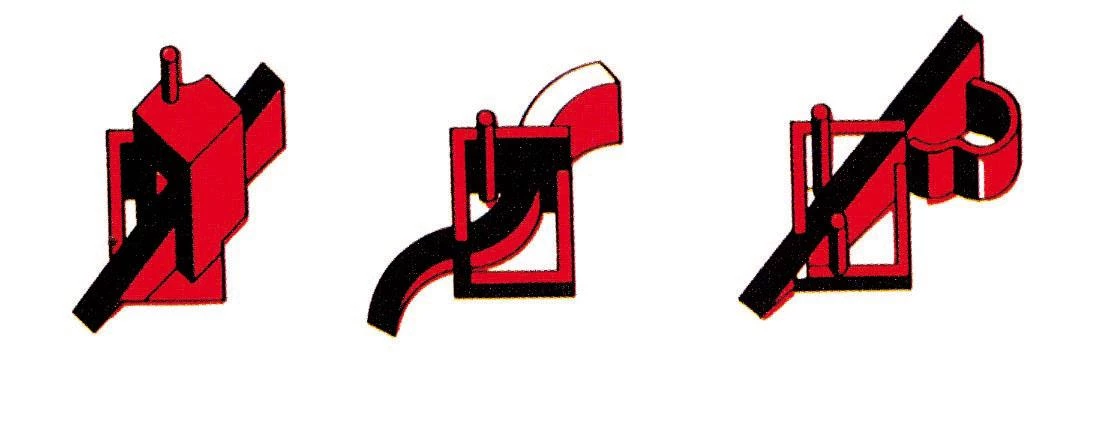

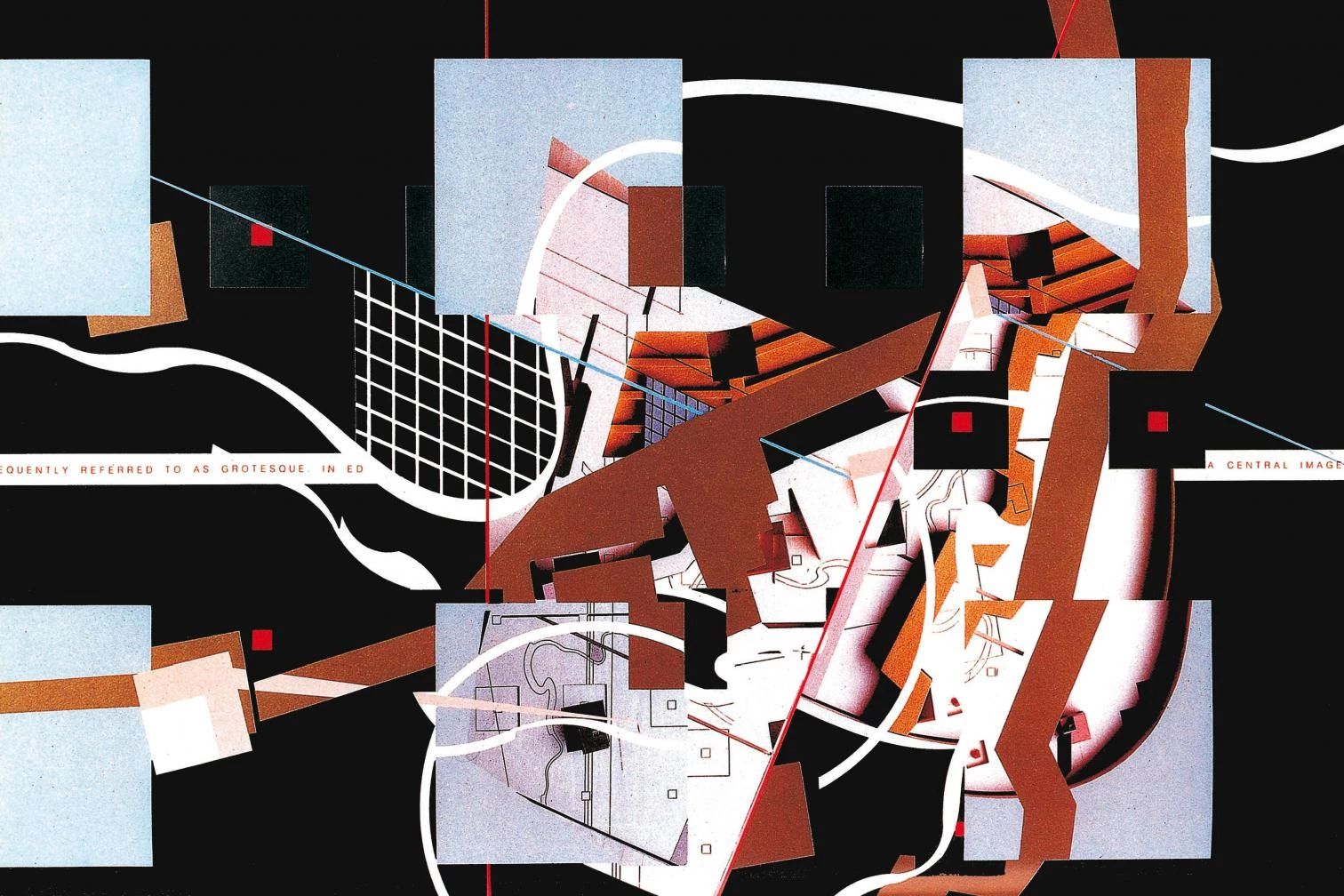

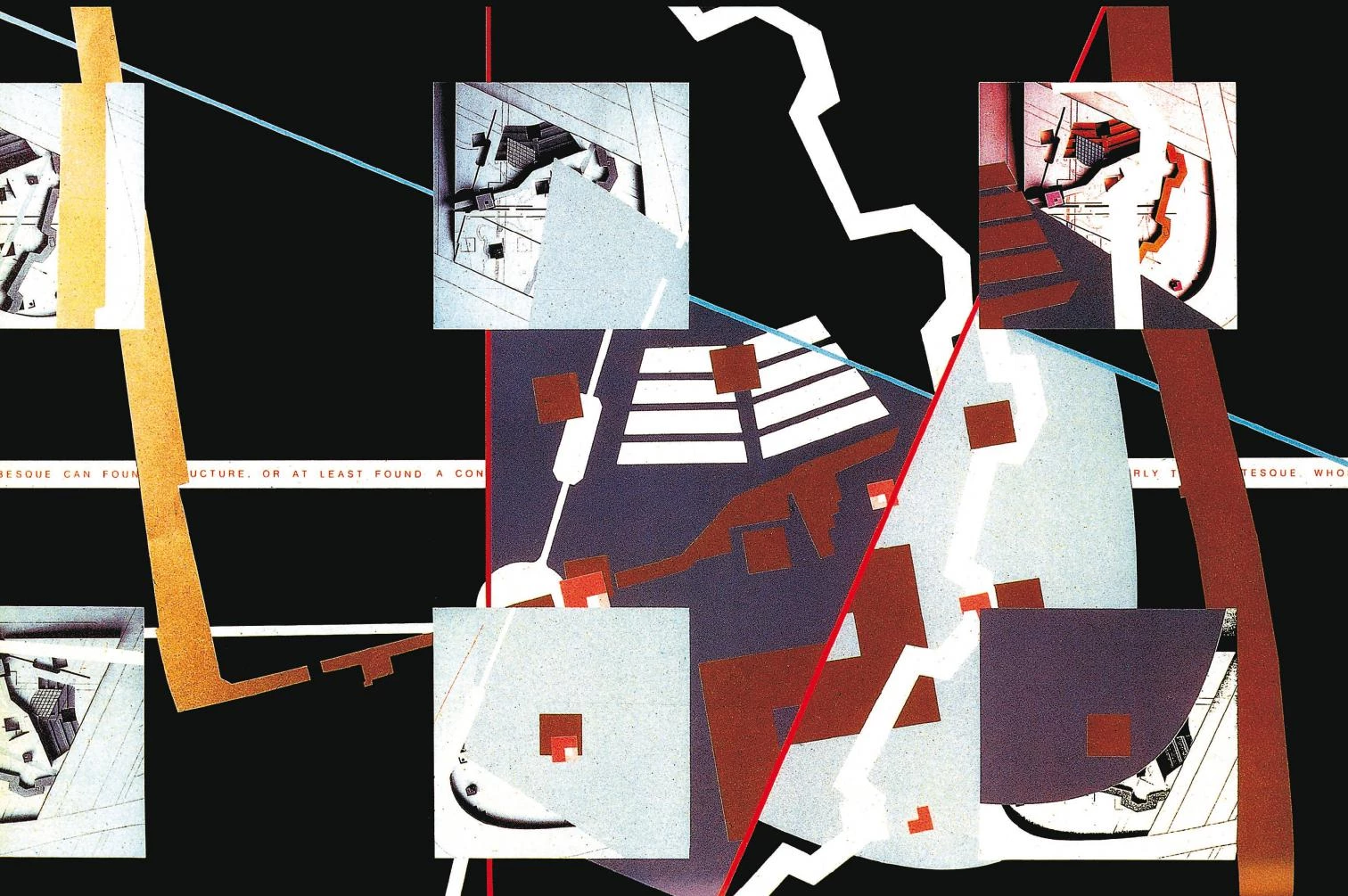

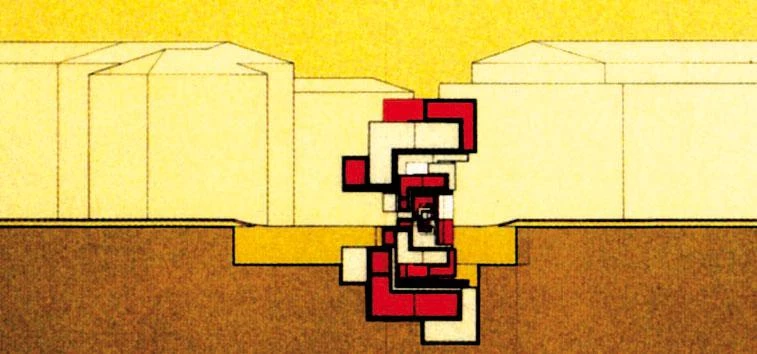

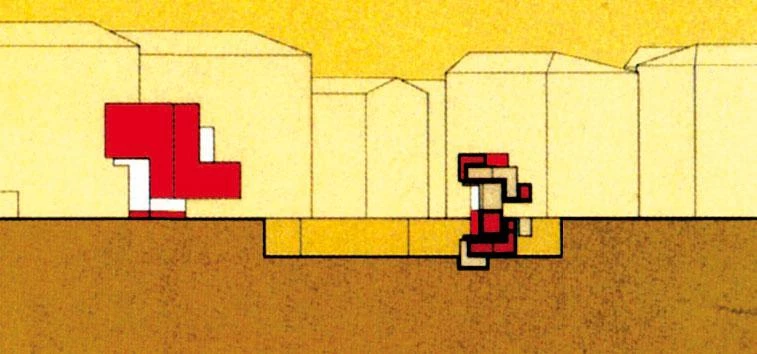

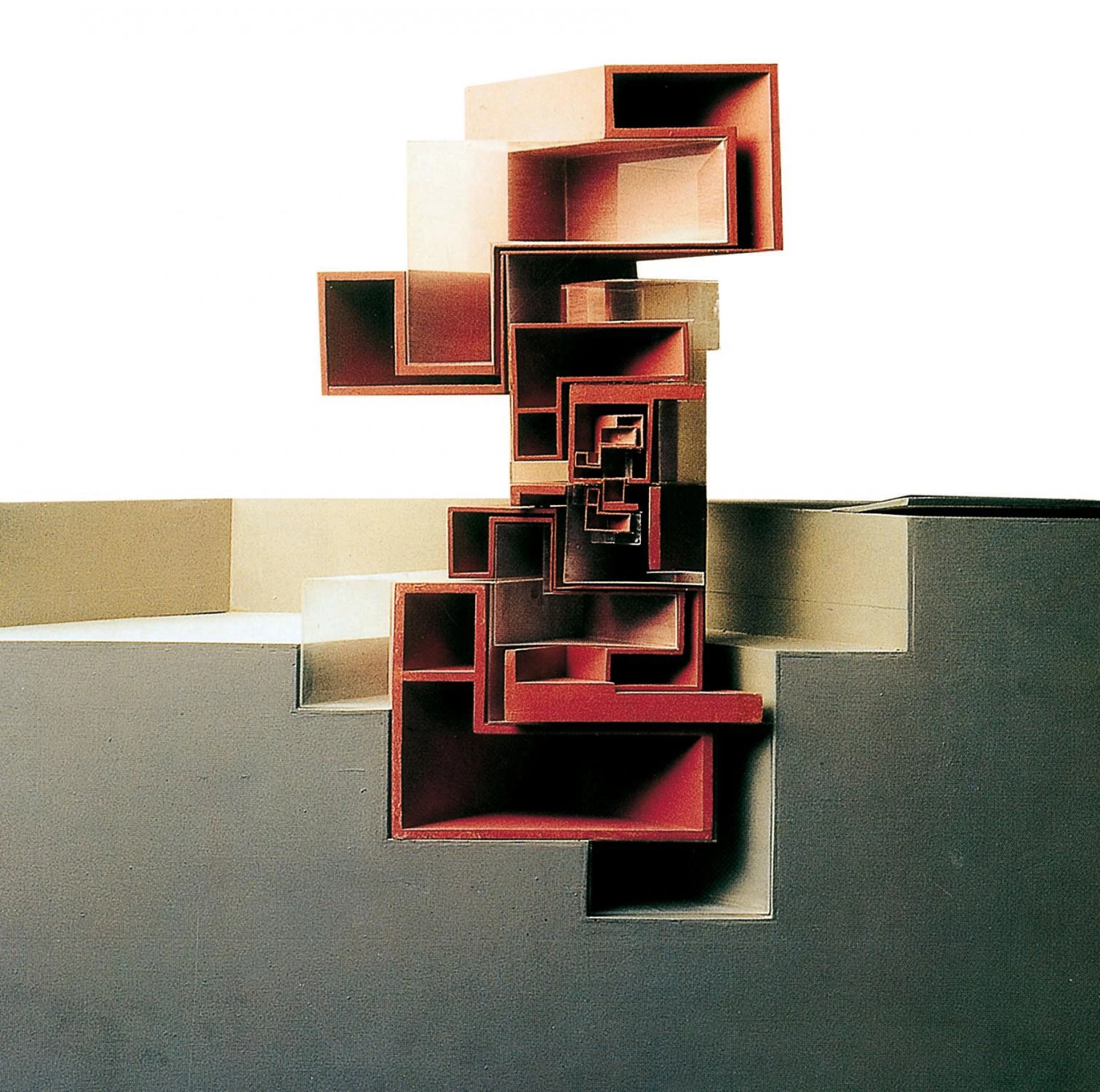

Peter Eisenman’s corbusian project for the Cannaregio of Venice clearly influenced the winning proposal by Bernard Tschumi in the competition for the remodelling of La Villette park in Paris.

As much the regular grid of the two proposals as their systematic alteration with formal elements and their enhancement with rhythmic variations are seen as architectural expressions of theoretical deconstruction.

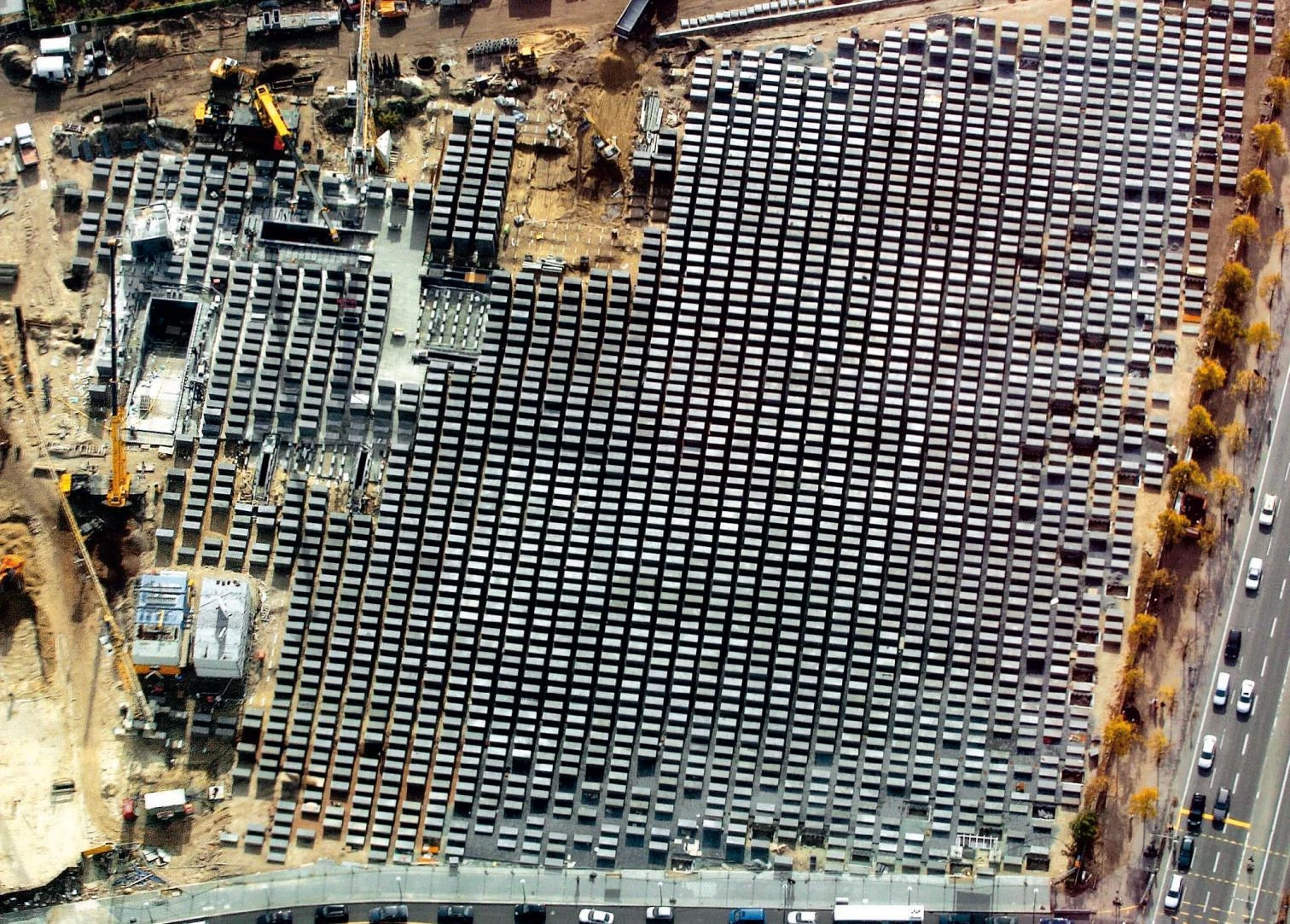

Now Eisenman wraps up his Jewish memorial in Berlin, and one cannot help seeing this gridded concrete labyrinth as a lapidary symbol of deconstruction and a horizontal cenotaph of a movement that Derrida’s death has rhetorically concluded. The philosopher and the architect staged their intellectual drifting apart with a famous epistolary exchange that the magazine Assemblage published in 1990. Here Derrida raised such disparate issues as God, Jewish space, or the opposition between the immutability of glass and the fragility of the ruin, and Eisenman reacted to this extensive palimpsest of absence and distance by expressing indignation at the implicit rejection of his work and at the same time relief at the declaration that it could not be considered deconstructive. I tried to bring them together for a final conversation, but illness made a farewell ceremony impossible. In his last letter to me, seven months before his death, Derrida mentioned the tumor and chemotherapy as the reason to decline the invitation. “De surcroît, je ne vous cacherai pas que, s’agissant de l’architecture aujourd’hui, je me sens moins compétent et moins inspiré que jamais.”

The folies drawn up by Tschumi in the knots of the grid that covers the park of La Villette also have a precedent in those imagined by Eisenman for the Venetian Cannaregio.

Many have considered deconstruction, with its demolishing or dismantling of ideological scaffolding, as an intrinsically architectural activity that reveals the internal structure of thought systems by decomposing their elements while reducing them to rubble. But in a world where George Bush presents his campaign strategist Karl Rove as ‘the architect’ of victory, and where Bill Gates describes himself as ‘the chief architect’ of Microsoft, deconstruction takes on a metaphorical breadth that breaks through philosophical architectures to become the colloquial term used by Woody Allen in Deconstructing Harry or the chef Ferrán Adriá in his ‘deconstructed cuisine’. Fifteen years after the exhibition in the MoMA – recently reopened after a rebuilding by Taniguchi with a canonic modernity diametrically opposed to the deconstructivist vanguard then promoted in its walls – the magnificent seven are all stars of the architectural firmament. Of the movement sparked by their fractured forms, nothing remains but blurred traces and scattered ashes. In the words of the critic Michael Speaks, “theory was interesting, but now we have work.”