Hexagonal Reflections

The elections in France coincide with the decline of the ‘grands projets’, in a wealthy and uncertain country which demands more security than identity.

France is no different. After the lay papacy of François Mitterrand, who profiled his place in history through a series of grands projets for Paris, the bicephalous France of Jacques Chirac and Lionel Jospin offers voters a plain track record and a bloodless project. Neither of the two candidates to the presidency has that “certain idea of France” that was an engine for the foundational regime of General De Gaulle, and neither do they, incumbent president and prime minister, present in their back-to-back platforms anything more than a tepid continuity of a conformist panorama where meaty promises and a rhetorical fidelity to ‘French exceptionality’ are only used to color a placid consensus for a growing cultural and economic globalization: democracy and architecture à la francaise are none other than thematized versions of global democracy and global architecture.

In the struggle to preserve its cultural identity, France uses architectural weapons: Lacaton & Vassal have recovered the Palais de Tokyo in Paris (above), and Jakob & MacFarlane, the Pont Audemer theater (below).

In a world of blurred frontiers, the very idea of national schools reeks of stale convention. Though we still refer to British high-tech, Swiss laconicism, or Dutch experimentalism, we know that these stenographic denominations are archaisms of convenience, occasionally useful for publicity but entirely devoid of true substance. When SuperDutch was published in the Netherlands, where such kind of architectural marketing has reached paroxysmal levels, the representative of this hypothetical Dutch school, Rem Koolhaas, simply commented, “Imagine how we would puke if there were a book called SuperGermans; laugh at SuperBelgians, snicker at SuperFrench, complain about SuperAmericans... This is a ridiculous moment to base the notion of a new architecture on a national identity”.

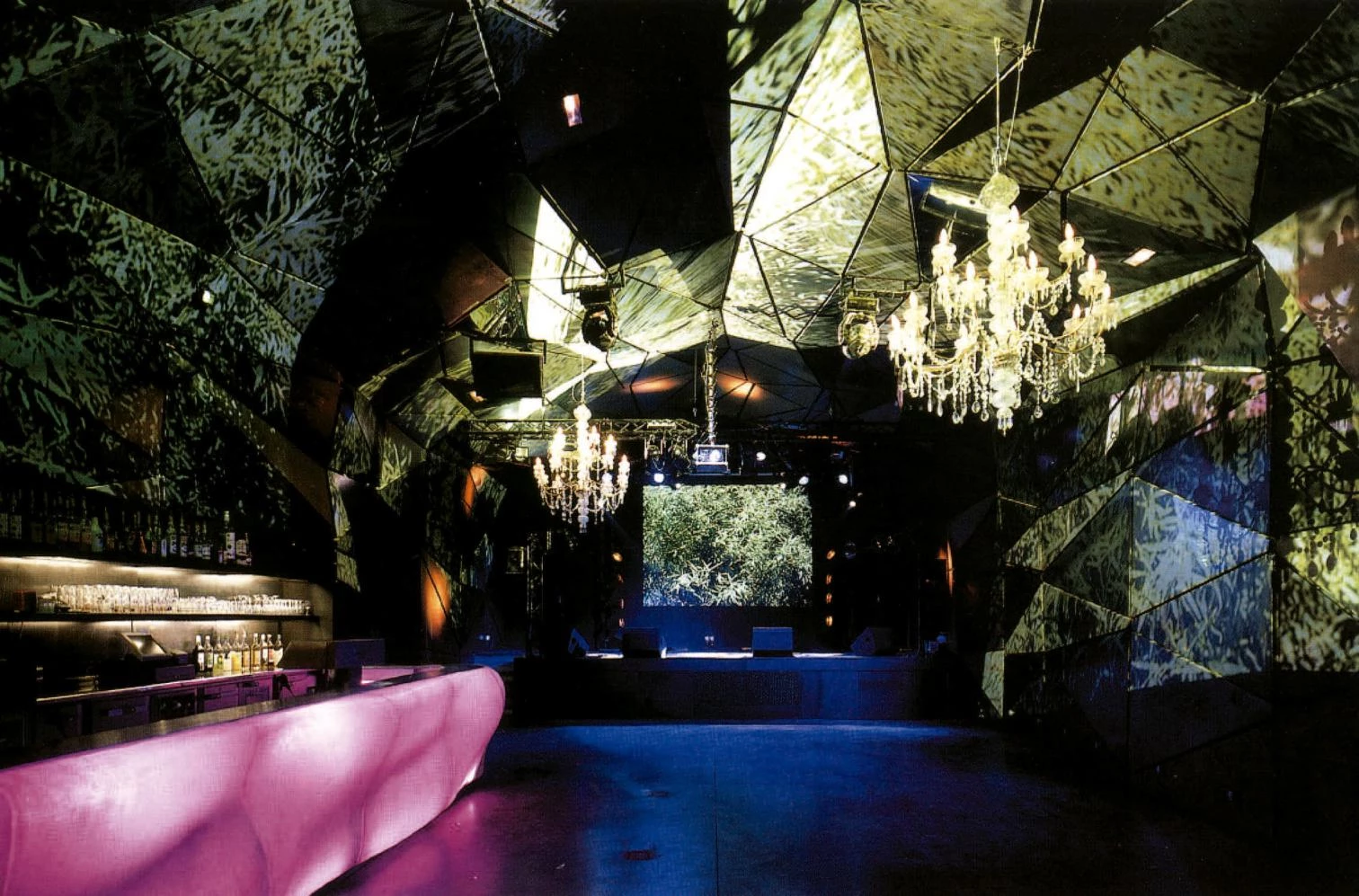

The stylistic panorama, polarized until yesterday between immaterial construction and sculptural corbusianism, is now more diverse and disperse; left and below, the Nouveau Casino in Paris, by Périphériques.

This may be true, but French architecture and democracy do manifest, despite everything, certain distinctive features that on another electoral occasion were admirably presented by Eric Rohmer in L’arbre, le maire et la médiathèque, a pedagogical comedy where the superfluous nature of a building is weaved with trivial political intrigues, describing the great urbanistic and ecological dilemmas of our times from the tiny laboratory of an idyllic village. Although their solid self-esteem have not yet produced a volume of SuperFrench, the cultural di-mension has been so characteristic of the Fifth Republic that architects have motives to expect much political and budgetary attention, and reasons to hope that their works will be differentiated from the unanimous trend of corporate building.

Such resistance to globalization is, in fact, resistance to Americanization, and the architectural debate is but a chapter of a more general controversy about Europe’s capacity to maintain its own cultural and political personality in an increasingly homogenized world subjected to the material and ideological hegemony of the United States. No matter how often such assertion of identity is an empty gesture, defending camembert against McDonald’s or the right of the Parisian Disneyland’s employees to sport a moustache, the defense of French uniqueness eventually leads to a project of European autonomy that insists on rescuing EU countries from their manifest destiny: becoming an American protectorate, where the organization of the territory and the forms of urban growth, as well as the economics of construction and the symbolic models of architecture, come from the metropolis..

The idea of France embodied in the heritage inventories and cultural centers of De Gaulle and his minister André Malraux underwent a significant transformation with the grands travaux – which after the Pompidou Center had their heyday with the 1981 election to the presidency of François Mitterrand, who with the help of the minister Jack Lang promoted and spearheaded the French capital’s last series of great cultural works – and again experienced an inflection with the last collection of media libraries and museums scattered all over its geog-aphy: republican values were replaced by a monar-chical, mediatic colossalism, and this in turn gave way to a decentralized and disoriented agitation. If the grandeur could be prolonged as a spectacle, the current ‘democracy of proximity’turns French cultural exceptionality into an empty slogan.

In the last decade, some architects believed to have found in the forms of Le Corbusier a cultural reference and critical weapon against the invasion of immaterial and mediatic architecture, which they considered a tool of technocratic consumerism and an expression of the society of spectacle. But if French architecture was historically characterized by geometric monumentality and technological innovation, both cylinders of concrete and cubes of glass had legitimate stylistic credentials; in the end, the industrial, futuristic refinement of the Nouvels or Perraults would win over the sculptural Corbusianism of Ciriani and his disciples. This may not necessarily have been a triumph of the global over the local; nevertheless, evidently it was a victory of the mediatic over the old “wise and magnificent play of volumes under the light.”

This publicitary, narcissist and elegant architecture, whose landscapes of luxury and reflections juxtapose public uses and private programs, blurring the limits between institutions and commerce to marry culture with fashion, is of course an efficient representation of a prosperous, hedonistic, and cynical country: a disenchanted nation that is no longer the France of Marguerite Yourcenar but that of Michel Houellebecq. This skeptical France, more concerned with security than with identity, is in the end the quintessence of an aged and decadent Europe, a continent that proves as inefficient when it tries to maintain order in its own Balkan backyard as when it attempts to mediate in the religion and petrol conflict of the Middle East, and which confronts the migratory flows that are transforming it with a mix of reticent acceptance of ‘politically correct’ multiculturality and hidden fear of seeing cathedrals surrounded by mosques.

Tras los grandes proyectos de Mitterrand para la capital llegó una etapa de descentralización, de la que son fruto obras como la brasserie de Nouvel en Estrasburgo (arriba), o la mediateca de Du Besset y Lyon en Troyes (abajo).

Finally any exegesis of the hexagon must refer to the bittersweet legacy of the grands projets, whosecolossal shadow inevitably falls on the electoral de-bate. According to Le Monde, four mastodons of culture – the National Library, the Bastille opera, the Louvre, and the Pompidou – swallow up a fourth of the ministry’s budget only in operational expenditures, and together suffocate a cultural manage-ment that is paying the hyperbolic invoice of the tenure of Jack Lang. In the newspaper’s opinion, France will in future have to build less, decentralize more, and spend better. In sum, “be Malraux with the children of Lang.” The politics of museums, which is replacing investments with labels, so that the trademark Musée de France becomes as prestigious a tag as those of the grands crus, fashion, or perfume, is a good example of this new intelligent austerity. France is no longer different, but its cul-tural imagination remains a model for all.