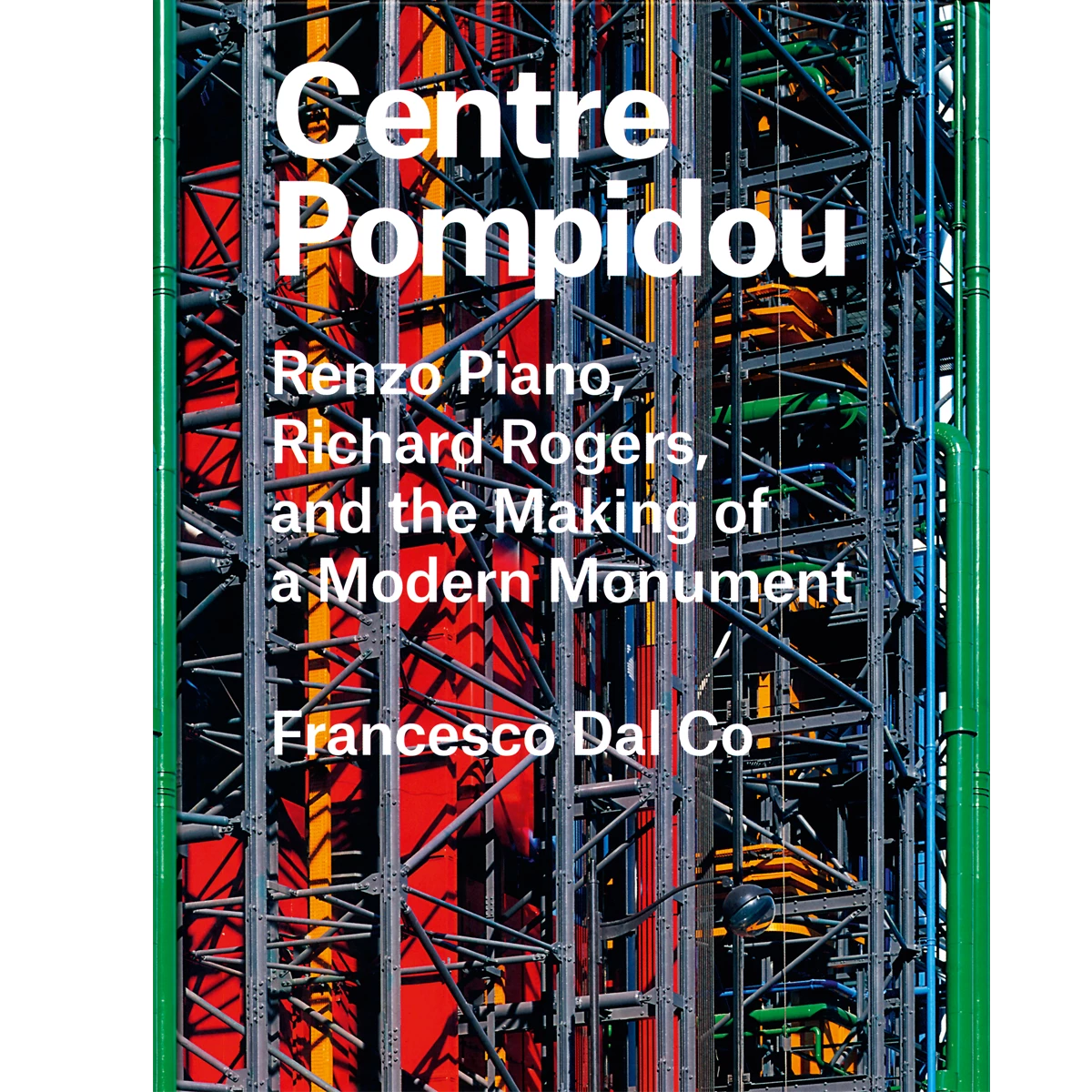

Few buildings deserve an intellectual biography and the Pompidou is one of them. On the occasion of its anniversary, the historian and critic Francesco Dal Co has masterfully braided together the narratives behind this extraordinary work, where the political and cultural effervescence of 1968 Paris interwove with the technical creativity of the Anglo-Saxon world, resulting in one of the icons of the 20th century: an accidental monument that became a symbol of a radical and optimistic time. Expanding an essay published in Italian in 2014, Dal Co now offers in English a compact and vibrant book, free of academic scaffolding but solidly based on previous literature. Aware that no historian can narrate the past ‘as it really happened,’ the Venetian professor and editor of Casabella makes his own interpretation to free the Beaubourg of its ‘invented tradition.’

The opening salutes Georges Pompidou, who as President of the Republic launched a revolutionary building, a product of the intellectual and aesthetic tsunami of 1968 but also nourished by the structural lightness of 19th-century metal constructions like Les Halles – demolished in 1971, when the Beaubourg competition was announced. Lamenting that his predecessor De Gaulle did not leave a building to be remembered by (despite the charisma of his Minister of Culture, André Malraux, who planted Maisons de la Culture all over France), Pompidou firmly supported this new kind of museum, described by some as a permanent World’s Fair of art and technology, and which would open in 1977, three years after his death. Dal Co comments on the inspirations for the project, which go back to Piano and Rogers’ formative years and to their shared admiration for Buckminster Fuller, Frei Otto, or Jean Prouvé (who chaired the competition jury), but also to the British engineering tradition then represented by Ove Arup’s office, with figures like Ted Happold, Peter Rice, or Tom Barker.

As a popular palace of culture (the closest thing there is to a state religion in France), synthesis of a technological Arcadia and a Parisian arcade, the Centre Pompidou is intellectually indebted to the Fun Palace of Cedric Price and Joan Littlewood – the goddess of agitprop theater – and Dal Co shows that its link to that “mechanical temple for the homo ludens,” as Reyner Banham defined it, is more pertinent than the frequent reference to the apolitical and antigravitational pop graphics of Archigram. The Pompidou’s architects were builders more than they were draftsmen, and its story is told, like the building itself, ‘piece by piece,’ from the mythical ‘gerberettes’ to the fusion of composition and construction in the rear facade, so different from the side facing the plaza, in the ‘speaking architecture’ tradition of Boullée, Rodchenko, Bayer, or Nitzchke, enabling visitors to take in the city transformed into merchandise, as before from the Eiffel Tower. If you wish to pay tribute to the building on its anniversary, read this small book by a great historian. You will not regret it.