Art Museum, Milwaukee

Santiago Calatrava- Type Museum Culture / Leisure

- Material Concrete Glass

- Date 1996 - 2001

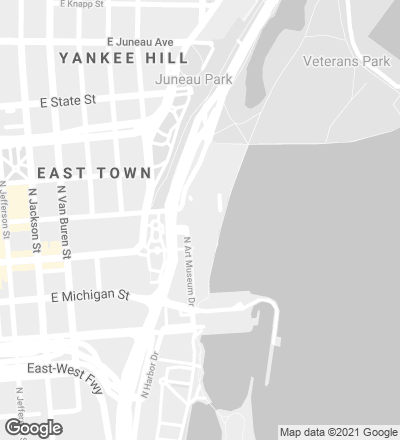

- City Milwaukee

- Country United States

- Photograph Alan Karchmer Timothy Hursley James Brozek

Joseph Giovannini

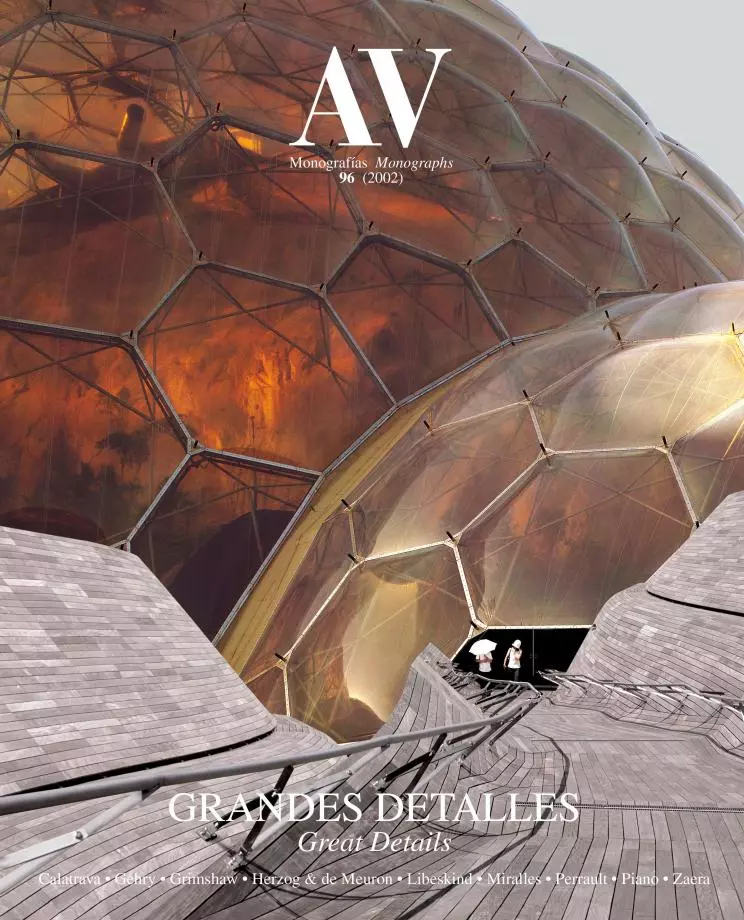

With its two angled masts suspending a monumental glass dome and bridge from fanning webs of cable, the entrance pavilion to the new Milwaukee Art Museum seems spectacular enough. But at the push of a button, a pair of huge sunscreens lifts off the sides of the elliptical dome and gradually spreads until it achieves full reach, looking like an eagle poised to land, wings feathering to a point. Designed by Santiago Calatrava, the screens consummate the vista at the east end of Wisconsin Avenue, the main thoroughfare of the town, like the Victory of Samothrace at the top of the heroic flight of stairs at the Louvre. When it is flying, Calatrava’s building is an event that captivates citizens, who actually stop and watch from overlooks along the city’s Lake Michigan waterfront. Like the Guggenheim Museum in Bilbao, in Spain, this is a building that entrances, breathing new life into an older metropolis. Santiago Calatrava is making Milwaukee famous again.

Many buildings imply motion, but though they may look dynamic, they do not actually move. Calatrava, however, has been studying the geometry of building movement since his doctoral thesis in engineering on the foldability of space frames, and in Milwaukee, he has turned the idea into a form of urban ballet. He deliberately sited the spectacle at the terminus of Wisconsin Avenue in order to reconnect the city to its abandoned waterfront. For his first museum and first American building, the Spanish-born architect inflated architectural rhetoric and scale to create a dramatic figural form that would anchor one pole of the city while establishing a presence on the vast lake beyond.

Triple Link

The museum was originally located in the basement of Eero Saarinen’s 1955War Memorial, before Milwaukee architect David Kahler extended it east toward the lake in 1975. The identities of the memorial and museum have always been muddled, and in response to director Russell Bowman’s desire to give the museum an independent identity, Calatrava relocated the entrance from the back side of the building to a position a full city block south, and hyphenated his new entrance with a long, low wing for temporary exhibitions, an auditorium, museum shops, and two long sculpture galleries.

Calatrava is both an engineer and an architect, but also a sculptor whose abstract artworks adhere to the modernist tradition of reductive purity typified by Constantin Brancusi’s work. Calatrava belongs to a generation of masters who hybridize disciplines (the way architect Eisenman imports philosophy, and Gehry imports art). Calatrava, however, is unique because he bridges three fields: he sculpts, engineers, and designs, producing works of unusual disciplinary integration and scope.

As a spectacular landmark, the wings and dome tie the waterfront to the city visually, but Calatrava makes the connection from the high ground to the water with a long narrow footbridge asymmetrically suspended from one of the masts by a web of cables. He shapes the cast-in-place concrete bridge in smooth, organic curves that diagram the flow of forces. The bridge leads to the museum entrance’s ‘beak’, since in profile, the southern facade resembles the flanks of Saarinen’s birdlike TWA Terminal at John F. Kennedy Airport. With his light yet monumental forms, Calatrava achieves the critical mass necessary to lure people from the city to an entrance that resituates and redefines the museum. From the bridge, a double stairway and an elevatorlead down to the foyer, and an Alexander Calder mobile hovers over a circular stairwell leading to a 100-car garage. (Visitors who drive to the museum in what may be the most beautiful garage in the world, with its lithe, white structural concrete ribs supporting the ceiling like vaulting in a Gothic cathedral.)

Wisconsin is Frank Lloyd Wright territory, and as Wright did in the houses like Wingspread just down the coast in Racine, Calatrava bursts space open just beyond the foyer. The structural lines of the reception area under the great glass dome angle obliquely so that you feel as though you are falling up. The hall’s glazed prow points to Lake Michigan, offering a conquering view commensurate with the vast scale of the Great Lake. Calatrava divides the museum functions north and south of this transept. The service core to the right, with the kitchen, bathrooms, and restaurants, forms a circular apse in what emerges as a cathedral plan.

The structure to the left of the transept inaugurates a visit to the museum proper. Incandescent white interiors and natural light glowing on pristine curves are bounded front and back by long, archetypal sculpture galleries “as in the Louvre or the Prado” says Calatrava. The tall space between the galleriesis subdivided,loaflike, alongitslengthinto the temporary exhibition hall, a museum shop, and the auditorium. Calatrava structures this wing not with a grid of columns but with arching ribs that bifurcate like wishbones, extending into the basement parking and up to the roof. Each pair of skeletal arches defines a bay and, in the two long, outlying galleries, frames a sculpture; hidden sources of light wash the wall surfaces in between, beatifying the artworks, like in the side altars of a baroque church. The whole wing acts as a link connecting the new entrance hall to the lowest floor of the existing museum (itself reorganized and refurbished).

The engineering may be elegantly acrobatic, but the floor plan has the straightforwardness of a traditional European cathedral. Arches organize the spaces, and the architect fits the program neatly into the structure. Yet the disparity between the plan’s simplicity and the complexity of the section creates a conceptual warp within the 40,000-square-foot addition. Why does an engineer so inventive with structure fall back on a plan without comparable spatial invention? The plan expresses no movement, just a sense of organization. And why is it symmetrical? “Why not?” responds Calatrava. “I wanted to achieve great clarity in the plan. The first problem was to address the connection to the city. The second was creating a sectional structure that defines the form, and then the functional needs that define the plan. The pulsation of space is given by the section”. With its simplified plan and clear hierarchy of parts, the three-dimensional composition is classically ordered and surprisingly unevolved – out of sync with the more sophisticated engineering of, say, Calatrava’s bridges.

For all the structural pyrotechnics, Calatrava has created a closed formal container that does not open easily to the site or even within itself to its interior spaces. The building’s containing skin is not more conceptually advanced than the boxlike galleries within. In the context of its traditional plan, engineering seems reduced to decoration. The dialogue between disciplines within Calatrava’s practice has not equally advanced each individual discipline. Traditional typological thinking holds back the engineering and the sculpture. Still, it is hard to argue with the sheer joy this exuberant museum has stirred in Milwaukee. The whole building, even given its conceptual shortfall, is worth its flying roof.With a fairly simple mechanism, Calatrava has brought real movement to architecture. With his inventiveness as an engineer and talent as a sculptor, he has not only reclaimed the waterfront, but rejuvenated the city. For architecture, he has opened up a major subject about transformability and time: the building is an event, bravely raising the curtain on the notion of the city as urban performance...[+]

Cliente Client

Milwaukee Art Museum

Arquitectos Architects

Santiago Calatrava

Colaboradores Collaborators

Kahler Slater (arquitectos asociados associate architects); Graef Anhalt Schloemer (estructuras structure); Ring & Du Chateau (instalaciones mechanical and electrical engineering), CG Schmidt Inc. (gestión construction management)

Fotos Photos

Alan Karchmer / ESTO, Timothy Hursley, James Brozek