DG Bank, Berlin

Frank Gehry- Type Headquarters / office Commercial / Office

- Material Glass

- Date 1995 - 2001

- City Berlin

- Country Germany

- Photograph Roland Halbe

Francesco Dal Co

Berlin played host to a gigantic monster, born of the history of Europe. It took form in 1961 and survived for twenty-eight years. Then, with apparent haste, it was gone. Every moment of its demise was recorded and broadcast live. The fall of the wall was a unique and incomparable spectacle, displayed on television screens all over the world, through images of the dispersal of a nightmare, of edifying value for all. But each and every chunk of cement produced by the hammers that were used to smash the nightmare has left a deep mark on the land, and not only in the immediate vicinity of what had been a no-man’s-land at the center of a city. More than ten years have passed since then. The rubble has been cleared away and cellists can no longer perform sonatas in their honor and their presence, as in the autumn of 1989.

Since then Berlin has become a gigantic forge. Countless worksites have been opened to reconfigure its order and recompose its parts, in an attempt to mend, pursuing memories and myths, the wounds of a lacerated history. But nothing has really been mended in Berlin.Walkingthroughthe city one senses that ten years cannot suffice to give time the chance to claim the title of the great constructor: 1989-2001, the space of the immediate, a mere instant in the history of a city. For this reason Berlin unwittingly offers prompt confirmation of the observation of Ernst Jünger: cities “with their tangle of architectures and their innovations that completely transform their visage every ten years, are gigantic factories of forms: and yet, for they are cities, they possess no form”, we read in Der Arbeiter.

The attempts made in the years of the reconstruction of Berlin to impose a style on the anarchy of the energies accumulated in this instant that separates usfrom 1989 have been pathetic. Efforts have been made to conceal the monsters that have contributed to define the history of the city and the new aberrations that mark its development beneath a waxen visage with a reasonable, reassuring expression, just like the regulations and recommendations that have moulded its features. But because the objective pursued by the Berlin authorities is simply that of transmitting these impressions, the layer of wax is often so thin that it cannot hide the leer on the face below. If today we attempt to make an incomplete and necessarily provisional assessment, we can only conclude that the reconstruction of the city of Berlin has been a wager from which it would be unwise to expect any winnings. The bet was lost as soon as the chips hit the table.

Potsdamer Platz has been there for a few years now, to confirm this impression; the images it offers could easily be used to illustrate the passage from Der Arbeiter quoted above. An even more eloquent case can be found nearby, around the Brandenburg Gate and the Pariser Platz. In the new Reichstag restored and reconfigured by Norman Foster technology gutted of any meaning and coherence transforms one of the most disturbing monuments of the history of Europe into an empty spectacle. Commonplace spectacularization of a repressed memory, the new Reichstag seems to have been restored to its non-original functions with the aim of eliminating the stratifications accumulated by the past and modeled by time. We get the same impression looking at the facades around the Pariser Platz, resigned and polished so that this space, with the Brandenburg Gate as its backdrop, will communicate no troubling emotions, nurturing the nostalgia that has created it.

A Declaration of Intent

Among the shiny facades of the Pariser Platz one notes, at number 3, a volume whose diversity is perceptible at the very first glance. A succession of solids, of tall pilasters clad in stone (a stone similartothat utilized by Carl G. Langhansforthe Brandenburg Gate), that rise in steps, without summing themselves up in a top. The lack of limits and conclusions is the principal characteristic of this facade, actually a pure rhythmical pattern. Between the pilasters that form a flat gigantic order, without comment, the openings appear as a sequence of dark, hollowed parallelepipeds protected by inclined, brutal, terse panes of glass. Also free of any comment, set into the masonry, these windows confirm the fact that the composition of the elevation is intended as a declaration of a programmatic rejection of the Gemütlichkeit (familiarity) and the Traulichkeit (intimacy), one is tempted to say, that the visitors to the square are invited to appreciate.

Eight years have passed since Frank Gehry began work on the project for the multifunctional building of Pariser Platz 3. Various difficulties slowed down the construction process and delayed its completion. Thinking back on his other works in this same period, one might imagine that Gehry, in the design of the elevation on the square, had complied with the guidelines (or perhaps, in this instance, it would be better to say “the climate”) imposed on the architects commissioned to design the various episodes in the more or less ambitious building projects completed – or still in progress – in Berlin. But this is not the case. The facade of Frank Gehry’s building on Pariser Platz, as we have noted, has nothing affected or self-satisfied about it, and it is certainly not playful or seductive. Intentionally incomplete, it appears as an unsociable fragment. Like a splinter, it inserts itself in one of the most important urban spaces of Berlin, a strident presence with respect to its surroundings, to the gracious, apparently cultured streetfronts facing the square of the Brandenburg Gate. This construction speaks a language that expresses a different history than the one represented, here in the heart of the city, as a pleasant spectacle of harmony and composure.

The fact is that Gehry, once again, has given voice to the culture of which his architecture is the mosttimely expression. Its roots havethe same vigor possessed by those of the rugged modes of design practice which form the backbone of the history of architecture in the United States, starting with the years of the Gilded Age, illustrated by the works of Frank Furness and Henry H. Richardson. Rejection of conventions, pragmatic experimentalism, freedom opposed to nostalgia, reduction of history to an arsenal of materials available for all uses, usability as a principle: these are the teachings of the irreverent, barbaric contaminations of Furness or the primitive tectonics of Richardson. The approach of Frank Gehry is similar (and equally wily). Behind the screen that is placed over the structure on Pariser Platz – a facade that displays only its indefinite repeatability in a place where every construction is presented as unrepeatable we find a fragmented organism, completely concealed from the outside world. To the rear, on Behrenstrasse, the construction has an image that has nothing in common with that of the main facade. The succession of the windows, slightly protruding, inserted in a variously curved surface, gratified to the point of appearing to have been borrowed from another construction – evidently a self-citation –, has nothing in common with the good manners of the new Berlinese architecture and, above all, with the mimetism that marks so many of its episodes.

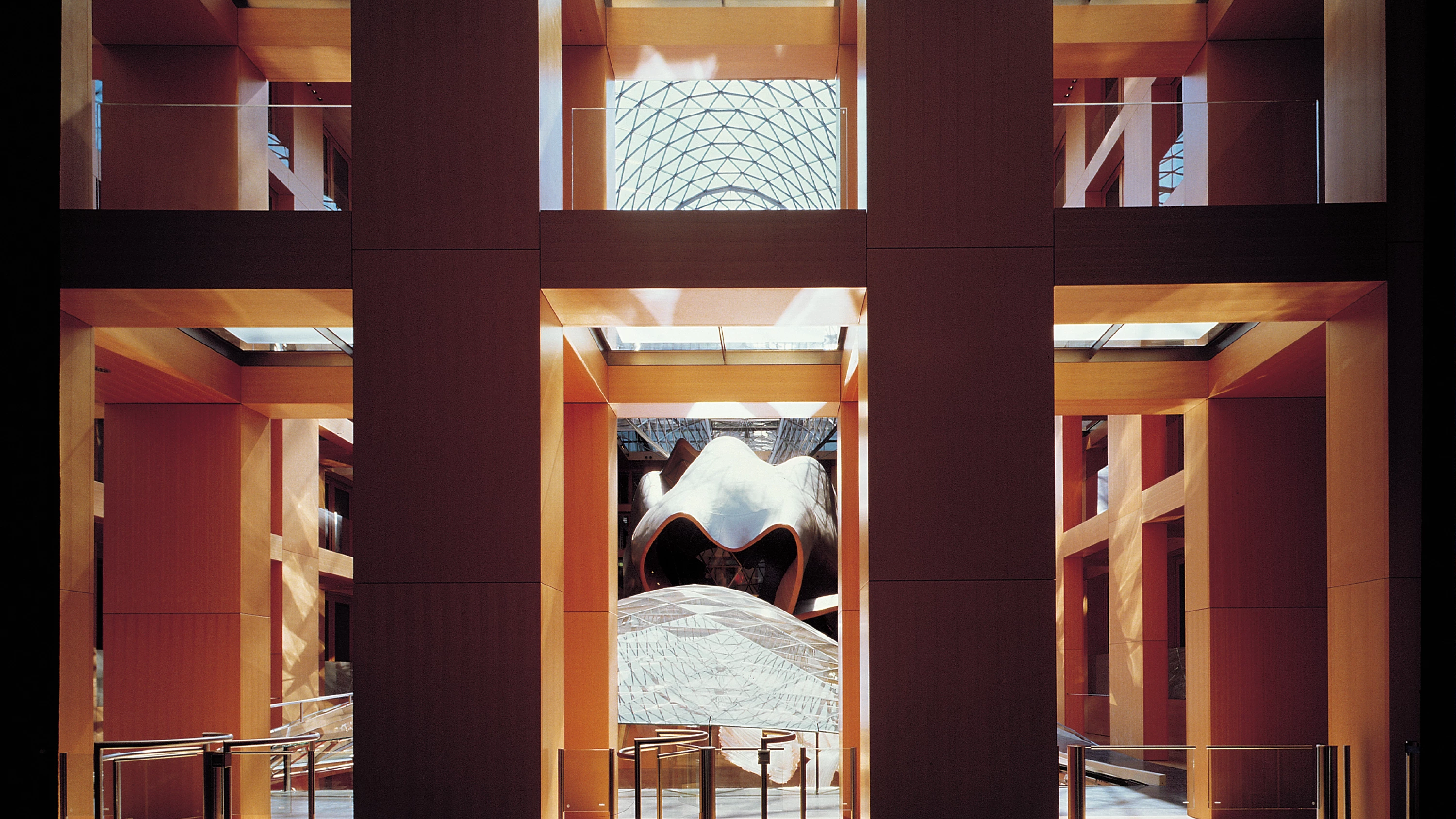

While the rhythm of the elevation on Pariser Platz does not fit in, with the energy which characterizes Richardson’s dissonances, with its surroundings, inside, in a dilated, emptied space, tormented by transparency, beneath a large glazed cap that emerges from the roof as if it were the back of a big fish, a surprising although not totally unexpected spectacle is staged.

Here the Californian architect picks up the dialogue that, through multiple mediations, he maintains with the Dada artistic experiences. The spectacular mingling and amazing mixing of materials and figures he realizes in the gutted womb of the building is a display of virtuosity. A montage of figures gives form to the vast void like a succession of caverns, one inside the other, updating a technique utilized by Kurt Schwitters in the Merzbau. Barbaric in its open lack of justification, in its self-referentiality, this spatial succession is arranged around the profile of a gigantic bucranium that seems to have been lifted from a painting by Georgia O’Keeffe (under the cap, modeled by a second masterfully shaped enclosure, we find a common space and then an auditorium). With its osteological configuration this form gives the space an unexpected admonitory meaning. In a disarming gesture, making an arbitrary decision, Gehry couples the Dada technique with a figure whose origins like in the desert of Santa Fe. In this way he evokes a monstrosity and, at the same time, offers the possibility of grasping the distance of the many nightmares his collage causes to materialize.

The building on Pariser Platz is also concealed by the mask of two different elevations of which one – we have now discovered – is simply a gigantic theater curtain. Its full and empty segments are the shadows produced by the folds of the velvet. Behind these folds, in contrast with what happens in some many other constructions of the new Berlin, the space is subjected to a horripilation. With its evident, radical gratuitousness and lack of basis, the polymateric bucranium evokes the countless monsters from which Berlin futilely struggles to free itself, as the city itself sees to the their reproduction in the attempt to derive its own form from the process. In vain, as we can now understand by taking a walk at Pariser Platz...[+][+]

Cliente Client

DG Inmobilien Management

Arquitecto Architect

Frank Gehry

Colaboradores Collaborators

R. Jefferson, C. Webb, M. Salette, T. Takemori, L. Tighe; Müller Marl, Schlaich Bergermann (estructura structure); Brandi (instalaciones mechanical); A. G. Licht (iluminación lighting); Munich (acústica acoustics)

Fotos Photos

Roland Halbe