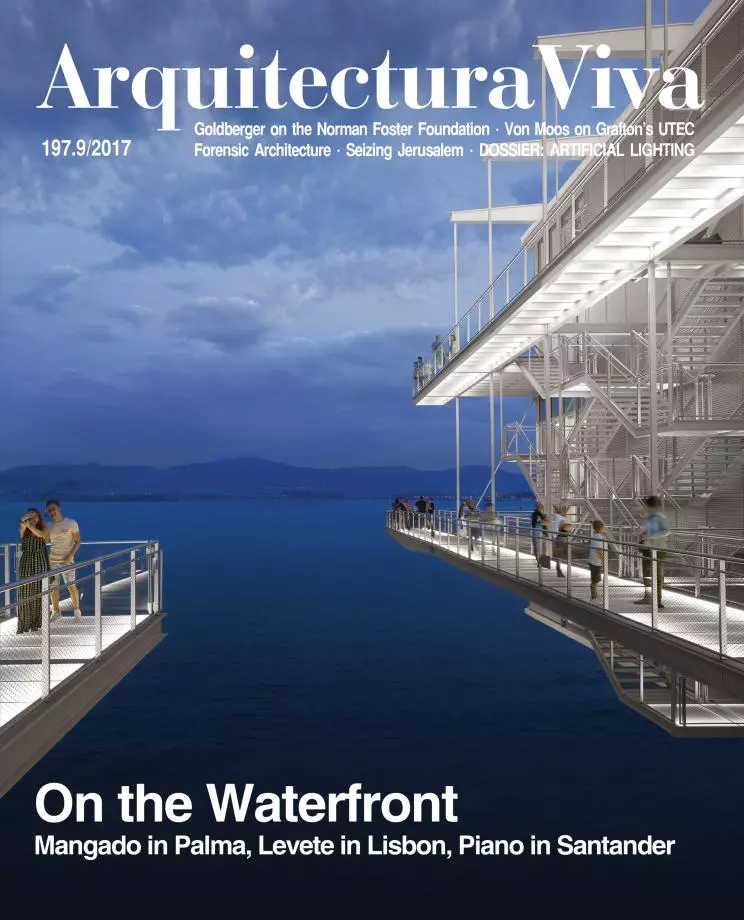

Museum of Art, Architecture and Technology (MAAT), Lisbon

AL_A (Amanda Levete Architects)- Type Museum

- Material Ceramics

- Date 2016

- City Lisbon

- Country Portugal

- Photograph Piet Niemann Fernando Guerra FG+SG Hufton + Crow Alejandro Villanueva

- Brand Panoramah! Disset

The cultural centre as landscape has become a recurrent trope of late. We find Frank Gehry doing it in Paris with his Fondation Louis Vuitton, a glass-and-stone hillock you can climb up to enjoy the Bois de Boulogne’s tree canopy; or, across town, there’s Jean Nouvel making a mountain out of his Philharmonie, complete with a cave, in a nod to the anti-Tschumi park that is the nearby des Buttes-Chaumont; and before either of them there was Snøhetta, in Oslo, turning a commission for an opera house into a glacier you can walk up or (in an ideal world) toboggan down. Amanda Levete and her firm AL_A faced a similar waterside situation with the new addition to Lisbon’s Museu de Arte, Arquitetura e Tecnologia (MAAT), and it’s primarily as an accessible public space that the majority of visitors, those who choose not to enter the museum, will experience the 20 million euro edifice, on a spectacular site on the banks of the majestic River Tagus, in the Portuguese capital’s Belém district.

MAAT is owned and run by the Fundação EDP, the non-profit social and cultural arm of Energias de Portugal (EDP, formerly Electricidade de Portugal), and is housed in two buildings: AL_A’s new Kunsthalle (commissioned by EDP CEO António Mexia in 2010) and the former Tejo Power Station just next door. A splendid brick-and-steel cathedral of thermo-electricity built between 1908 and 1951, the power station closed in the 1970s, and initially opened to the public in 1990 as an electricity museum. Now, however, with the creation of MAAT, it also contains a large amount of whitecube gallery space, installed by director Pedro Gadanho, who left MoMA to head MAAT in 2015.

EDP’s new institution joins a whole host of monuments and cultural sites in Belém, among which are the presidential palace, the monastery of the Jerónimos, the naval museum, Vittorio Gregotti’s Centro Cultural de Belém (1992) and Paulo Mendes da Rocha’s coach museum (2015). But all are cut off from the river by a major transport artery – eight traffic lanes and a railway – that stretches between the quayside and the inland residential district. At the time of writing, only two inadequate footbridges, a kilometre apart, span this formidable barrier.

“If EDP selected us, I think it’s because they appreciated our understanding of public space,” says AL_A director Maximiliano Arrocet. “After we first visited Lisbon, two things were immediately clear: we didn’t want to compete with the old power station, and we wanted to reconnect the site to the city. The idea of a footbridge was fundamental.” Scheduled for construction later this year, the bridge will spring from the residential district on the other side of the transport artery, landing pedestrians on MAAT’s roof. “The area around the springing point will be landscaped,” continues Arrocet, “so visitors’ experience of the museum will begin on the other side.”What visitors discover on arriving where the bridge will land is an 8,000 square meter lunar landscape of Moleanos limestone – as used for Lisbon’s famous calçada paving – above whose curvature surreally poke, as though pasted onto the sky, the pylons of the 25 de Abril suspension bridge and the statue of Cristo Rei across the Tagus (the estranging effect is reminiscent of the views of the Arc de Triomphe from Le Corbusier’s Beistegui apartment, or Magnum’s 1960s photos of Oscar Niemeyer’s Brasilia).

Unpublished Panoramas

Advancing up the steep incline, you reach a suspended balcony with stunning views of the estuary. But for AL_A, the view behind was just as important: “When you turn around and look back, you see the whole of Lisbon,” explains Arrocet, “a view that could previously only be experienced from a boat on the river.” This relationship with Belém is also expressed in MAAT’s restricted height. “We had quite a few meetings with the neighbours, who were terrified we would block their view,” he recalls. By sinking the interior 6 meters under grade, a low profile was achieved.

From the belvedere, visitors have a choice: a path that winds down to the highway at the rear; another that funnels you into the museum entrance; or lateral slopes leading to the quayside. It is of course on the waterfront that AL_A sets out to bedazzle, with a 190-meter-long elevation that rises at its centre into an enormous, cantilevercarrying inclined arch dressed in a scaly skin of 14,751 cream-coloured, high-glaze stoneware tiles. The result appears at once ‘iconic’ – in its formal freedom and engineering prowess, especially when viewed laterally – and low-key, when viewed from the water, like the brow of a gently rising hill. While sceptics may see only a gratuitous blob, the arch’s form, says Arrocet, was defined by the path of the sun, to ensure that at the hottest times of the year the space under it – containing the café, the entrance and a large skylight – is always in shade.

If the junction with the power station seems a little awkward, it’s because AL_A had to incorporate a new substation into the building, as well as integrating a safety perimeter around its attendant transformer. As for the tiles (profiled half-hexagons), they were designed with economy in mind, just three mould types being needed to make them. Not only are they a reference to the Portuguese tradition of cladding buildings in ceramics, they were also conceived to mimic the rippling of water and to reflect the surrounding light conditions, the association of energy and light being intended as a subtle evocation of the genius loci and its power-producing history. However, the tiles were both miscast and – thanks to hurried construction – poorly aligned, and have had to be rehung.

An Immersive Experience

There’s something a bit Bilbo Baggins about entering a building under the brow of a gentle hill, and the impression of a Hobbit burrow continues as you are channelled inside. Once past the entrance, museum-goers find themselves on another balcony, this time overlooking the main bravura space, a 1,200-square-meter oval hall that is column-free. Left exposed, at Gadanho’s request, to form a blackpainted technical ceiling, the impressive span of the steel roof is set off by a battalion of neon strips that materialise the ghost of the white false ceiling originally envisaged. MAAT’s Oval Gallery is of course the equivalent of Tate Modern’s Turbine Hall, a space for specially commissioned large-scale works (MAAT’s real turbine hall in the Tejo Power Station being unsuited for such a role, and instead hosting cocktails and public gatherings). While its form is a clear nod to Wright’s Guggenheim, it was also chosen for its structural stability, the concrete walls of the oval allowing AL_A to erect the column-free ceiling and cantilevered belvedere in a seismic zone.

AL_A imagined the museum as an immersive experience, and has created a sort of swirling vortex that begins on the roof and carries on inside via a very long ramp that winds down from the entrance to the floor level of the Oval Gallery (informed both by Frank Lloyd Wright’s Guggenheim and Lubetkin’s penguin pool, says Arrocet). Once at the bottom, visitors can cross the Oval Gallery to reach the all-white Main Gallery (1,050 square meters), which swirls round the building’s riverside perimeter and doubles back to the starting point, via a space known as the Project Room. On first visiting, when the museum was empty, I wondered how the conservators would handle these cavernous, non-orthogonal spaces conceived in the absence of a specific curatorial brief. “I remember an experiment we tried the first week after the pre-opening (October 2016),” says Gadanho. “We installed six pieces from the collection for another ten days, just for the public to be able to see the new building. Among them was a very large painting, which when we hung it here looked like a postage stamp stuck on the wall.”

In the five months since, in response to the found object he was given, Gadanho, also an architect, has taken a rather Merzbau approach, filling it up with all sorts of Cubist boxes that, as well as dividing the galleries into manageable chunks, provide black-box space for video art and straight walls for hanging paintings. A central feature of the Main Gallery is the giant skylight that allows the space to be flooded with indirect daylight bouncing off the ceramic-clad arch, but, for the majority of the exhibitions, it seems the curators will prefer to obscure either all or part of it in favour of artificial illumination.

As a space for exhibiting art, AL_A’s MAAT is perfectly adequate, even if you can never quite escape the feeling that the interior was always secondary to the exterior. As a piece of landscaping, however, the building has the potential to do something that neither the Oslo Opera, nor the Philharmonie, nor the Fondation Louis Vuitton achieve: once the footbridge has been completed, in addition to an object people climb, it will also become a space they traverse to get from A to B. In this it will be reminiscent of Rome’s Spanish Steps, both a place for gathering and a route through the city. MAAT’s roof is equipped, moreover, with outlets for outdoor events such as film screenings, giving it the potential to become a truly popular riverside piazza. To understand its potential, you only need look at photos of the 22,000 people who thronged there during the building’s initial unveiling. While MAAT is perfectly timed for the tourist boom that Lisbon is currently experiencing (some 3.6 million visitors in 2015, in a metropolitan area of 2.8 million inhabitants), it will also, just as importantly, give back to the local community.

Andrew Ayers, an architectural critic and historian, teaches at Columbia GSAPP.

Obra Work

Museo de Lisboa de Arte, Arquitectura y Tecnología Lisbon Museum of Art, Architecture and Technology (MAAT).

Arquitectos Architects

Amanda Levete / AL_A.

Consultores Consultants

PanoramAH! (carpintería window frame); Disset (sistema y montaje de fachada facade system and installation).

Fotos Photos

Hufton+Crow (pp. 30 arriba top, 37, 38, 39); Piet Niemann (p. 30-31); Fernando Guerra / FG+SG (p. 32 izquierda left); Francisco Nogueira (pp. 31 arriba top, 33, 34, 36); Alejandro Villanueva (p.35).