Synopses

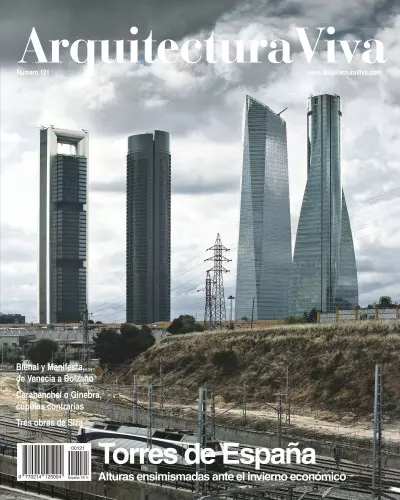

Towers of Spain. Optimistic icons of economic power, skyscrapers are acquiring new values in order to adapt to the ecological and social demands of vertical urban models. Four articles analyze the present and the future of the high-rise development of cities, the proliferation of towers designed by Spanish architects in their country and abroad, and comparatively examine the structures of two buildings in Barcelona and the facades of the four skyscrapers that have been recently inaugurated in the city of Madrid.

Contents

Iñaki Ábalos

Verticalism

Vicente Patón

The Path of Giants

Robert Brufau

Shell and Cantilever

Ramón Araujo

High-Rise Gowns

Ten National Projects. As much in the cold northern part of the Peninsula as in the warm south, Spanish cities are adopting vertical growth with residential or office projects that will change their skylines, if the financial circumstances so allow. This fertile reproduction of towers in the country is illustrated with a helical hotel in Gijón; a glass piece in Bilbao; a colossus of precise offices and a pair of opposites at the Fira of L’Hospitalet; a thin screen in Barcelona; an organic design in Madrid; a complex of orthogonal blocks in Málaga; two volumes in Seville – one with an elliptical floor plan and the other zigzagging – and a duet of epigraphic cylinders in Cádiz.

Heights of Madrid. The grounds formerly occupied by the Real Madrid Sports Complex, in the northern part of the capital, have provided the site for a recently inaugurated complex of skyscrapers that, under the name Cuatro Torres Business Area (CTBA), will become a new financial center of the city. It includes the tower of stacked boxes by the British studio, the slender black volume by the Spanish office, the faceted prism by the Argentinian architect and the sculptural aerospatial building by the American firm.

FOA/Zaera & Moussavi, Gijón

Pelli Clarke Pelli, Bilbao

Mangado, L’Hospitalet

Ito & b720, L’Hospitalet

Perrault, Barcelona

Estudio Lamela, Madrid

Alonso & Balaguer, Málaga

Pelli Clarke Pelli, Sevilla

SV60, Sevilla

De La-Hoz, Cádiz

Norman Foster

Torre Caja Madrid

Rubio & Álvarez-Sala

Torre Sacyr-Vallehermoso

Pelli Clarke Pelli

Torre Cristal

Pei Cobb Freed

Torre Espacio

Views and Reviews

Italian Biennials. The Manifesta 7 concentrates in Bolzano the most recent works of contemporary art in Europe and the 11th Venice Architectural Biennial explores the more conceptual areas of design.

Art / Culture

Juan Antonio Ramírez

Remains and Souls

Richard Ingersoll

‘Povera’ Architecture

Visual Collections. Two exhibitions reflect upon the nature of photography; a vast archive of documentary images is presented in Barcelona and several perspectives of urban life are displayed in Madrid.

Jaume Vidal Oliveras

The Infinite Register

Elena Vozmediano

Superimposed Views

Personal Relations. A biography of Le Corbusier and the publication of ten taped interviews with Philip Johnson unveil surprising sides of the author of Ronchamp and revealing stories about the ‘dean’ of American architecture.

Focho’s Cartoon

Paul Andreu

Various Authors

BooksRecent Projects

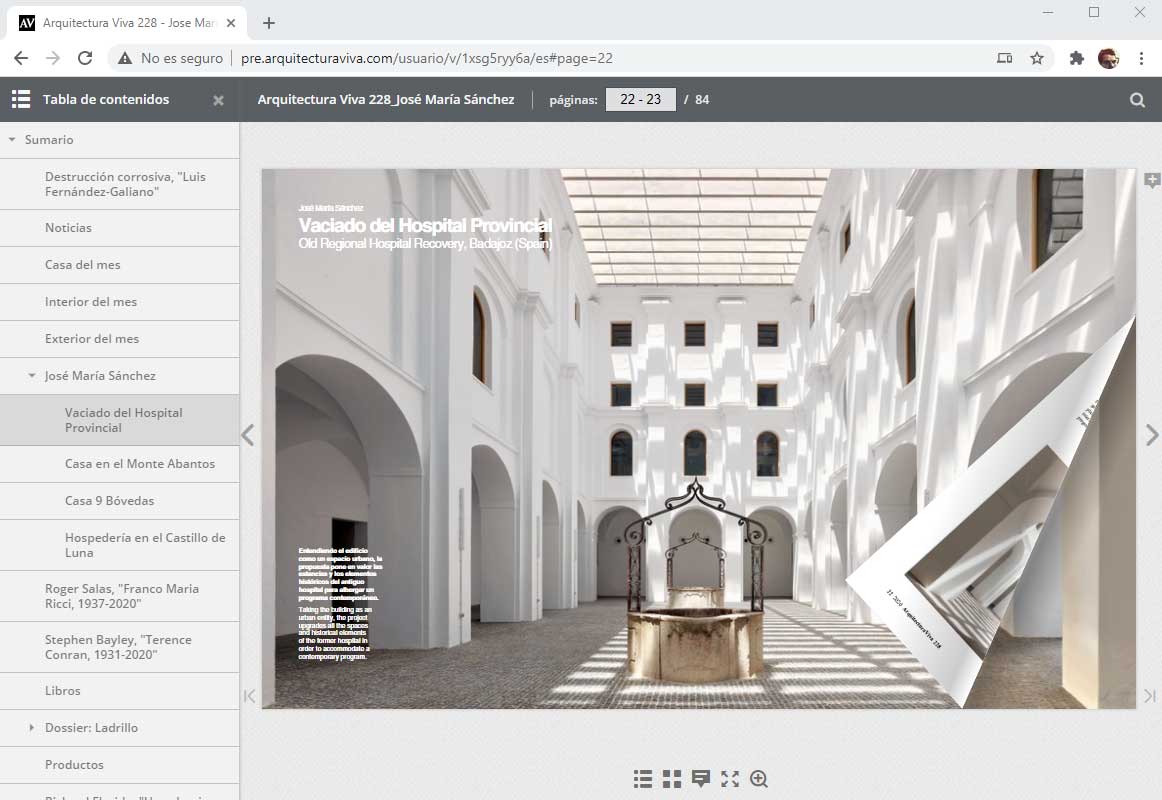

Three Works of Siza. A firm follower of the modern project, the Portuguese architect maintains his distinctive style in the purity of lines, the attention to context and monochromy. Three examples confirm these affinities: a museum in an old quarry in Brazil, an orthogonal library with views over the River Lima and a prismatic winery in the silent landscape of Degolados.

Technique / Style

Lusitanian Embrace

Museum, Porto Alegre

Elevated Content

Library, Viana do Castelo

White Wine

Winery, Campo Maior

To close, the prison of Carabanchel, one of the main symbols of Franco’s repression, and its large dome, unique example of panoptic architecture, have been demolished in spite of popular opposition. Around the same dates, the cavernous dome painted by Miquel Barceló at the UN headquarters in Geneva sparked controversy due to its excessive cost.

Products

Decoration, Heating

English Summary

Towers of Spain

Juan Antonio Ramírez

Painted Domes

Luis Fernández-Galiano

The vertical vertigo

While towers soar, stock markets crash. The completion of the Burj Dubai, the tallest building in the world, coincides with the bursting of the Gulf’s real-estate bubble, and in Spain the four new Madrid towers reach their final height as markets collapse. As often before, the construction of high-rises comes with the ruin of economic expectations. Thus, the Great Depression that began in 1929 was marked in New York’s profile by the tops of the Chrysler and the Empire State, and that same year Madrid saw the opening of the Telefónica building, the first European skyscraper. Once again, the 1973 oil crisis coincided with the topping of the WTC towers and the Sears Tower of Chicago, which would successively be the tallest buildings of the planet, and when the crisis hit Spain a few years later, the completion in Madrid of the Windsor Building and the Bank of Bilbao tower would signal the country’s bust. In 1996, the bursting of the Asian bubble had its architectural correlate in the opening in Kuala Lumpur of the Petronas Towers, once again a world record coinciding with a crisis, and that same year Madrid saw the inauguration of the KIO towers, whose construction had been interrupted in 1993, becoming a symbol of economic decline and social despair during that period of Spanish democracy.

Today, the Burj Dubai has taken the top of the world to the Emirates while the financial crisis drags the economies into recession, and in our country the Madrid towers once again become the backdrop of a disturbing scenario, where the political and business muddles are braided around an international crisis that is intensified here by the housing market collapse: the conflicts around Caja Madrid, which bought its tower from Repsol, are tangled up with the efforts of the banks spearheaded by the Santander to avoid the downfall of Sacyr-Vallehermoso – owner of another of the towers – through the sale of its Repsol shares to the Russian energy company Lukoil, while insurance companies such as Mutua Madrileña, owner of the third of the towers, take stock of the toxic residue left by the real estate crisis, and construction companies such as OHL, owner of the fourth tower, strive to face the crash of the real estate sector. On this stage of intertwined intrigues, the four towers – instead of representing Spanish prosperity or Madrid’s ambitions – rise as a crepuscular symbol of the corporations whose irresponsible behavior has forced governments around the world to plan massive rescues.

It is not hard to understand why so many major banks and companies prefer the low-profile of business campuses to the vibrant visibility of skyscrapers. So it happened with the Santander, which commissioned Kevin Roche with the construction of its financial city in Boadilla del Monte, and so it will be in the case of the BBVA, which has recently presented the campus project by Herzog & de Meuron for their new Madrid headquarters, replacing the tower by Oíza in Azca; so it has occurred with Telefónica, which already occupies the campus designed by Rafael de La-Hoz, and so it goes for Repsol, which has entrusted its horizontal headquarters to the same architect. Only savings banks seem to demand a different urban presence, and just like La Caixa changed Barcelona’s skyline with vertical landmarks for companies of its group such as Agbar or Gas Natural, Caja Madrid also reaches for the skies and will transfer its logo from one of the KIO towers to that of Foster in the old training grounds of the Real Madrid. But savings banks’ status as semipublic entities allows them extravaganzas such as the one intended by Cajasol with a skyscraper that dwarves the Giralda facing the historic center of Seville.