On: Architecture, exhibition at the Swedish Center for Architecture and Design (ArkDes), Stockholm

The work of Bolle Tham and Martin Videgård could well be described with a title of August Strindberg. He published Utopier i verkligheten in 1885, the year of birth of Gunnar Asplund and Sigurd Lewerentz, masters of an architecture that had in their contemporary Sven Markelius and in the later Ralph Erskine, Carl Nyrén, and Peter Celsing moments of brilliance, but that has been depressed for decades. Tham and Videgård are today the most visible representatives of a generation that can restore Sweden to its rightful prominence, and who do so with a string of works that have in common being ‘utopias in reality’: efforts to recover constructive clarity, functional efficiency, and expressive elegance while respecting the contextual constrictions of reality. Strindberg’s book is a collection of brief narrations, and the corpus of Tham and Videgård is similarly a group of episodes that do not make an extended story, because in each case the physical and material environment leads to a different outcome.

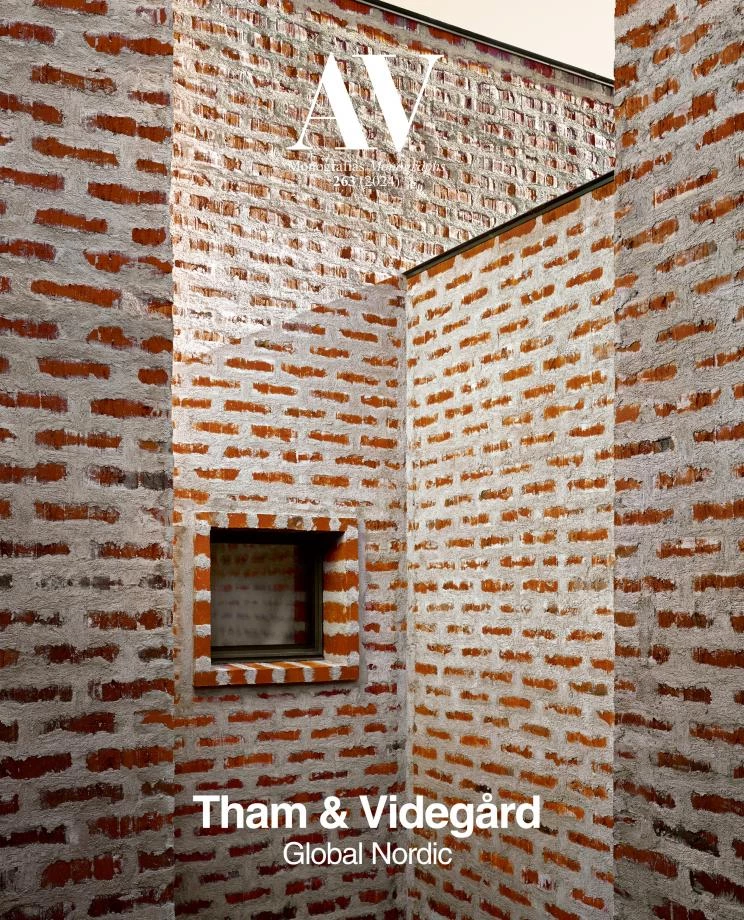

Palladians rather than Albertians, and Vitruvians in their devotion to the firmitas, utilitas, and venustas of the Roman, the Stockholm partners could be ascribed to Nordic classicism if they were not openly universal in their awareness of the global scene, and associated with a ‘retour a l’ordre’ if their search for simplicity did not exclude the imagination that makes each project a challenge of invention. But they are quite Nordic, though not in the somber tradition that goes from the existential angst of Ingmar Bergman to the noir universe of Stieg Larsson or Henning Mankell, but in the reasonable modesty of an egalitarian country, the perfect stage for the dissolution of authorship before the power of nature, and where design still feeds on the sources of its peasant past: a country that was able to harbor both the friendly impressionism of Anders Zorn and the theosophical symbolism of Hilma af Klint, and which goes well with the motto of Tomas Tranströmer, “half-finished heaven.”

In an itinerary that extends from the material and formal variety of the houses to the urban wisdom of the public buildings, heaven is half-finished in the unexpected floor plan of the Creek House and in the evocative section of Krokholmen, in the vertical aplomb of the Kalmar Museum of Art, and in the contextual intelligence of Nya Konst, expressions of an architecture that does not stop at interiors or landscaping, which disdains the immediacy of the present because it aspires to survive through adaptation, and which is direct without renouncing to spark the inspiration that remains in our memory. Of all the works, perhaps the most memorable is the most ephemeral, the design of their exhibition at ArkDes, conceived as a glass floor beneath which their oeuvre was displayed. In contrast to the shows that overwhelm, forcing to look up to the exhibits, in Stockholm visitors perceived them looking down towards a frozen pond: utopias in reality that last like insects trapped in the white amber of the museum.

Tham & Videgård, Summerhouse Lagnö, Stockholm