Balkan Urbicide

The deliberate destruction of the material, historical, and emotional heritage of the old Yugoslavia has caused in the region a genuine cultural genocide.

The first victim of wars is usually truth; in the Balkans, the first casualty has been memory. Physical and genetic genocide goes with urban and cultural genocide; the extermination of populations and mass deportations happen in simultaneity with the deliberate, systematic destruction of museums and archives. Rapes violate the freedom and dignity of women, but also the genetic heritage of the community under assault; the shelling of mosques and libraries destroys buildings of great historical and artistic worth, but also reduces to rubble the spiritual legacy of a human group.

In what was Yugoslavia, genetic memory and cultural memory are annihilated with equal cruelty: bodies and cities are ravaged, monuments and individuals mutilated, manuscripts and children sacrificed. In a war whose correspondents have not spared us the horror, the abyssal fright of human suffering has pushed the destruction of architectural and documental heritage to second place. But this destruction is happening on such a scale – and in such degree of detail – that it deserves a pause of attention.

The destruction of the National Library in Sarajevo was one of the most dramatic moments of the war, and the ruins became a symbol of the cultural genocide that the former Yugoslavia has been suffering.

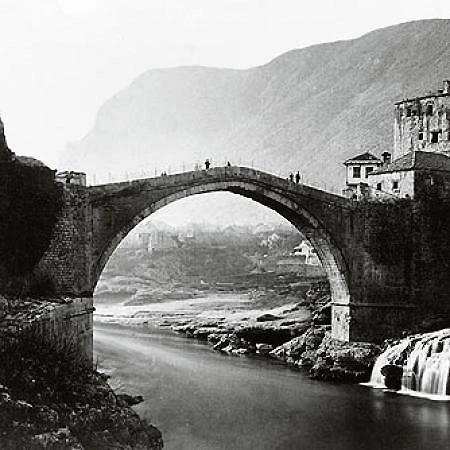

Fifty or so urban cores in Bosnia-Herzegovina and Croatia have been completely or partly destroyed. Places like Vukovar, Osijek, Gospic, Trebinje, Zadar, Karlovac, Dubrovnik, Mostar, and Sarajevo today form a litany well familiar to the reader of newspapers, but just a few years ago they were names most commonly found in travel guidebooks of what was Yugoslavia. The beauty of Osijek or the Baroque charm of Vukovar, on the Danube, were included in recommended itineraries; the Ottoman past of Mostar, the layered density – Muslim, Christian, and Sephardi – of Sarajevo, or the splendid Dalmatian beauty of Dubrovnik made these cities attractive destinations for the traveler interested in something more than the Adriatic beaches.

Over them fell a furious, devastating beast that has been described with a new noun, coined by both indignation and propaganda: ‘urbicide.’ That is how it was called by the Croatian voices that through a dozen texts and two hundred photographs documented the destruction of Mostar by Serbian forces from April to June last year. The architect Bogdan Bogdanović – who was mayor of Belgrade, where he still lives, from 1982 to 1986 – prefers to say “ritual murder of the city” when referring to the devastation wrought by this bitterly antiurban war. For their part, the orientalist scholars and intellec- tuals who have published pro-Bosnian propaganda in dailies have used the term ‘cultural genocide’ to describe the continued sacking of memory that is taking place in the Balkans.

Sarajevo Library

Urbicide, city murder, and cultural genocide are three different names for one same reality, the brutal destruction of the material, historical, and emotional heritage of a nation. The inevitable symbol of this immense catastrophe is Sarajevo, capital of Bosnia and of sorrow, whose National Library, which also held the university’s stock of books and the country’s newspaper collection, was bombed with incendiary grenades and reduced to ashes from 25 to 27 August 1992, losing a million and a half tomes and 150,000 manuscripts and rare publications. Serbian artillery had during the month of May, in Sarajevo, already razed the Oriental Institute and its valuable possessions, as well as the Mosque and the Gazi Husrev-beg Library, founded in the 16th century and depositories of a rich stock of illuminated codices, but nothing would express the horror as eloquently as the ruined vaults of the country’s principal cultural institution.

Mostar – another important city and the station, on the Neretva, of the Spanish Blue Helmets – saw the destruction, last summer, of its cathedral and thirteen mosques, six of seven historical bridges, and a good number of buildings of great artistic value, including the Franciscan monastery, which sheltered the main historical archives of Herzegovina. And this systematic demolition – never wrought by the accidents of combat, but always deliberately working to blind the forces of memory and reinforce ethnic cleansing with cultural hygiene – has been carried out all over the old Yugoslavia, in numerous places, most spectacularly in the destruction of hundreds of mosques but also targeting libraries, archives, and museums.

The radical devastation of built heritage that the Balkan conflict has brought affected mosques like that of Donjo Kamengrad (above) and bridges like the historic one in Mostar (below).

Recent Ruins

The determination to erase the past is equally evident in the early plans for reconstruction, which are already unashamedly taking shape on architects’ drawing boards, showing, for example, a new Vukovar rising in a picturesque Serbian-Byzantine style… But none of this will seem very strange to anyone familiar with the Spanish experience in what were called Devastated Regions, during our postwar 1940s. At the time, the writer Agustín de Foxá venerated ruins “because in them lie the faith and hate and passion and enthusiasm and struggles and soul of men,” and upheld the need for “recent ruins, new ashes, fresh rubble” as virile tributes to purification. Also during that time, visionary poets and architects dreamt in the same direction of landscapes cleared of human and stylistic impurities.

Perhaps the most significant thing about the Balkanic urbicide is that, far from obeying a blind and ignorant violence, it is part of the designs of a group of intellectuals of ardent views and inflamed words. As Bogdan Bogdanović reminds us, “the designers of the Bosnian horror are two or three poets of dubious talent, an unsuccessful historian of literature, and as the main strategist, a psychiatrist by profession and populist poet by vocation.” Paradoxically and inevitably, the authors of cultural genocide are the priests of culture.

With the help of European weakness, Serbian nationalists have set out to conquer the territory with their cultural mythology, invented traditions, poetic fabrications, and even architectural stylistic falsifications. A step behind but without a doubt outstanding disciples, the Croatian nationalists are similarly redesigning the landscapes of memory, and have started to try their hand at purging Zagreb’s streets of all communist and antifascist names that “disturb Croatia’s national identity,” sprinkling the city map with the surnames of notorious Nazis. Between the two opposed identities, Bosnia’s longtime multicultural and tolerant pluralism – which made Sarajevo ‘the Toledo of the Balkans’ – bleeds to death.

Under pressure from Germany, Europeans prematurely recognized Slovenia and Croatia, initiating a turbulence of unpredictable consequences. The subsequent recognition of Bosnia’s independence took place with the dogs of war already unleashed. As they howl, Europe’s leaders behave like those politicians in frock coat and top hat in the movie where the Soviet director Eisenstein made official cars and public buildings appear and disappear in fast motion, in a prolonged and ridiculously repeated action: quick, solemn, useless marionettes.

But European leaders are definitely as much to blame for events in old Yugoslavia as the likes of Milošević, Karadžić, Tudjman, or Boban. With their diplomatic irresponsibility they opened a Pandora’s box which they now are at a loss to close, and they had better find a way to seal it before the conflict spreads further. Today we can spot Krajina or Slavonia on the map, and we have become experts on the geography of the cruelty hitting the territory of Bosnia-Herzegovina, but we remain in innocent bliss about the toponymy of Kosovo or Macedonia, next scenarios of the Balkan war.

If we wish to maintain this pacific ignorance, our politicians have to understand, as Juan Goytisolo stresses, that “Europe is not dying in Maastricht, but in Sarajevo.” Urbicide is a contagious disease, spreading fast among neighbors but also to populations farther away. Although the rest of Europe’s cities seem intact, their hearts are starting to freeze, and they will soon be inhabited by corpses.