Mina de carbón a cielo abierto en Hambach (Alemania) © Bernhard Lang

Climate is not the problem, lack of governance is. Fifteen years ago I published an article, ‘Celebration of the City,’ which started by stating: “Climate is the problem, the city the solu-tion.” One year later, the Lehman Brothers crisis ushered in a period of global convulsions which questions that optimistic opinion. We thought that the 21st century had begun with the collapse of the Twin Towers on 11 September 2001, but most probably the crash of 14 September 2008 will mark a more significant milestone, because it hit the heart of the sys-tem. After the conservative ‘pink decade’ of the eighties, and the technological ‘digital dec-ade’ of the nineties, the bubble of ‘the real estate decade’ burst, starting a period of misrule that has replaced climate change as the main problem of our time. In fact, climate is not so much a problem as a context: if we are concerned about its alteration it is only because we have adapted to the current one, and both land use and the exploitation of resources are questioned when climate changes fast.

The debate on the energy transition to tackle the effects of climate change inevitably focus-ses on energy sources, and to a lesser extent on the amount of energy necessary to maintain our societies. Despite the many calls to reduce air travel or indoor temperature, contempo-rary hedonism is not very compatible with the appeals to control our carbon footprint through personal behavior or consumer decisions. Indeed, as much the energy needs of buildings as those created by the urban model and its impact on transport and mobility can be moderated through the thermal refurbishment of constructions and by promoting more compact and dense residential patterns, but both efforts can only pay off in the long run, and today it is urgent to act on sources. Taking for granted that the ultimate goal of a decarbon-ized economy is the exclusive use of renewables, the transition energies will most likely be nuclear and gas, with a probable future protagonism of hydrogen and electricity as the main networks for energy distribution.

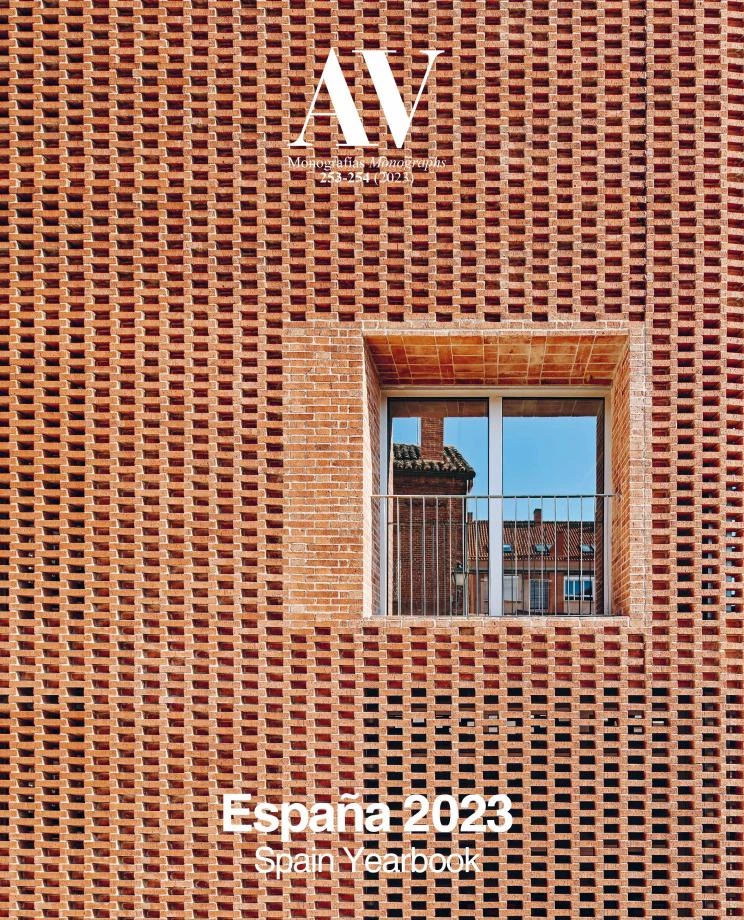

Since the Industrial Revolution we have grown in wealth and population through fossil fuels, and now we face the challenge of not depending on energy deposits but on flows. Such per-spective is both promising and menacing, because if during the past century the so-called ‘black gold’ created disfunctional petrostates where geological fortune distorted economy, society, and politics, the energy transition can produce electrostates capable of altering geo-political balances, because the non-ferrous metals on which the electrical revolution is based (copper, lithium, nickel, cobalt, silver, zinc, or aluminum) are unequally distributed, so we can expect measures like the Mexican reform of the Mining Law that has nationalized lithium. In Anéantir, Michel Houellebecq’s latest novel, the Minister of Economy of a future France de-votes all efforts to guarantee the supply of rare-earth elements, essential components of green technology, and it is possible that in this, too, the Cassandra of the Fifth Republic might have anticipated the key challenge of our time.

Successive reports drawn up by the United Nations on climate change have made it recommendable

to reduce fossil fuel use, but without suppressing coal extraction in exploitations like the Hambach mine.

El Mundo: El problema no es el clima

Extracción de litio en Bolivia © S. Broshevan / Depositphotos