At the mention of The Fountainhead, many will automatically think of the King Vidor movie; others, perhaps most people, will associate it with Gary Cooper; but neither the director nor the leading actor deserves as much recognition as the writer and philosopher Ayn Rand, the author of the novel on which the 1949 movie is based, who herself worked on the screenplay adaptation. Born in 1905 in St. Petersburg to a non-practicing Jewish family, Alisa Zinovyevna Rosenbaum wrote scripts since childhood, took up philosophy and history at university, made her reading of Aristotle, Victor Hugo, and Nietzsche compatible with her graduate studies at the State Technicum for Screen Arts, and emigrated to the United States in 1926 to settle in Hollywood and find her way as a screenwriter. She acquired US citizenship in 1931 with the name of Ayn Rand, and this prototype of the Russian intelligentsia, as she has been described, became an eloquent defender of American individualism against Soviet collectivism, and her influence spread to politicians and businessmen, including the future chairman of the Federal Reserve, Alan Greenspan, who for two decades would be the most powerful person in world finance, and was part of a group that gathered in Rand’s apartment to discuss her philosophical and social theses.

The writer’s ideas – which she expressed above all through her two great books, The Fountainhead of 1943 and Atlas Shrugged of 1957 (the latter has sold 25 million copies and the Library of Congress considers it the most influential book ever, second only to the Bible) – have clear echoes of her familiarity with Tolstoy, Dostoevsky, Chekhov, or Turgenev, who also promoted their worldviews through narrative and the theater, and even more with the Nietzsche of Thus Spoke Zarathustra, the Spengler of The Decline of the West, or the Ortega of The Revolt of the Masses, and crystallized in the philosophical system she named ‘Objectivism,’ a capitalist realism that defends enlightened selfishness and empirical judgment. Widely respected as a philosopher (she recently made the cut for The Visionaries: Arendt, Weil, Rand, Weil, and the Power of Philosophy in Dark Times, by Wolfram Eilenberger), Ayn Rand sought to reach the larger public through the novel, and even more through cinema, where she had started her writing career with screenplays.

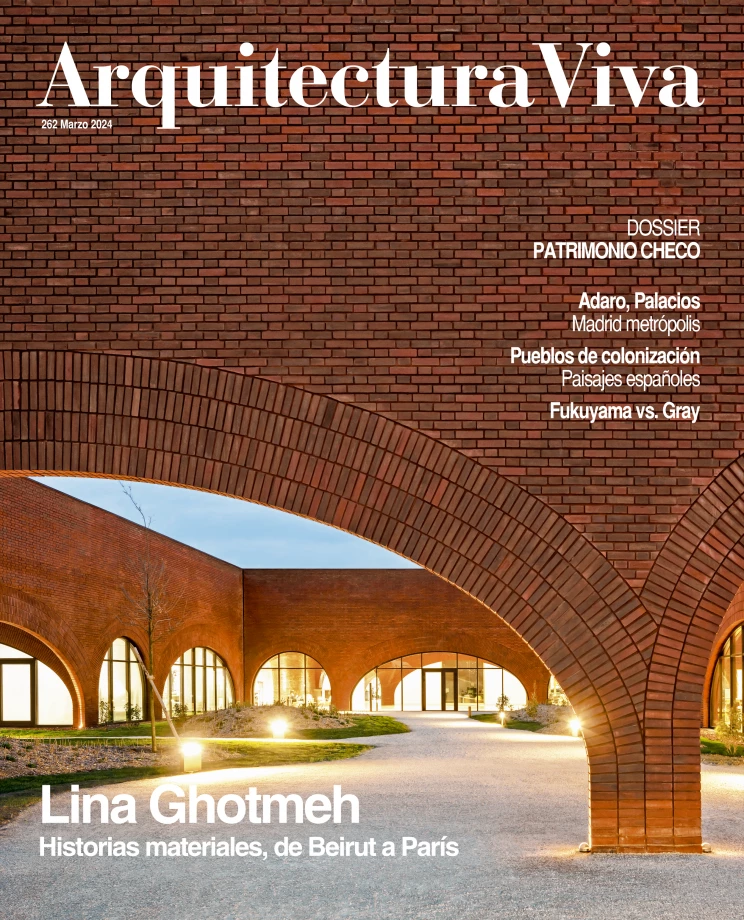

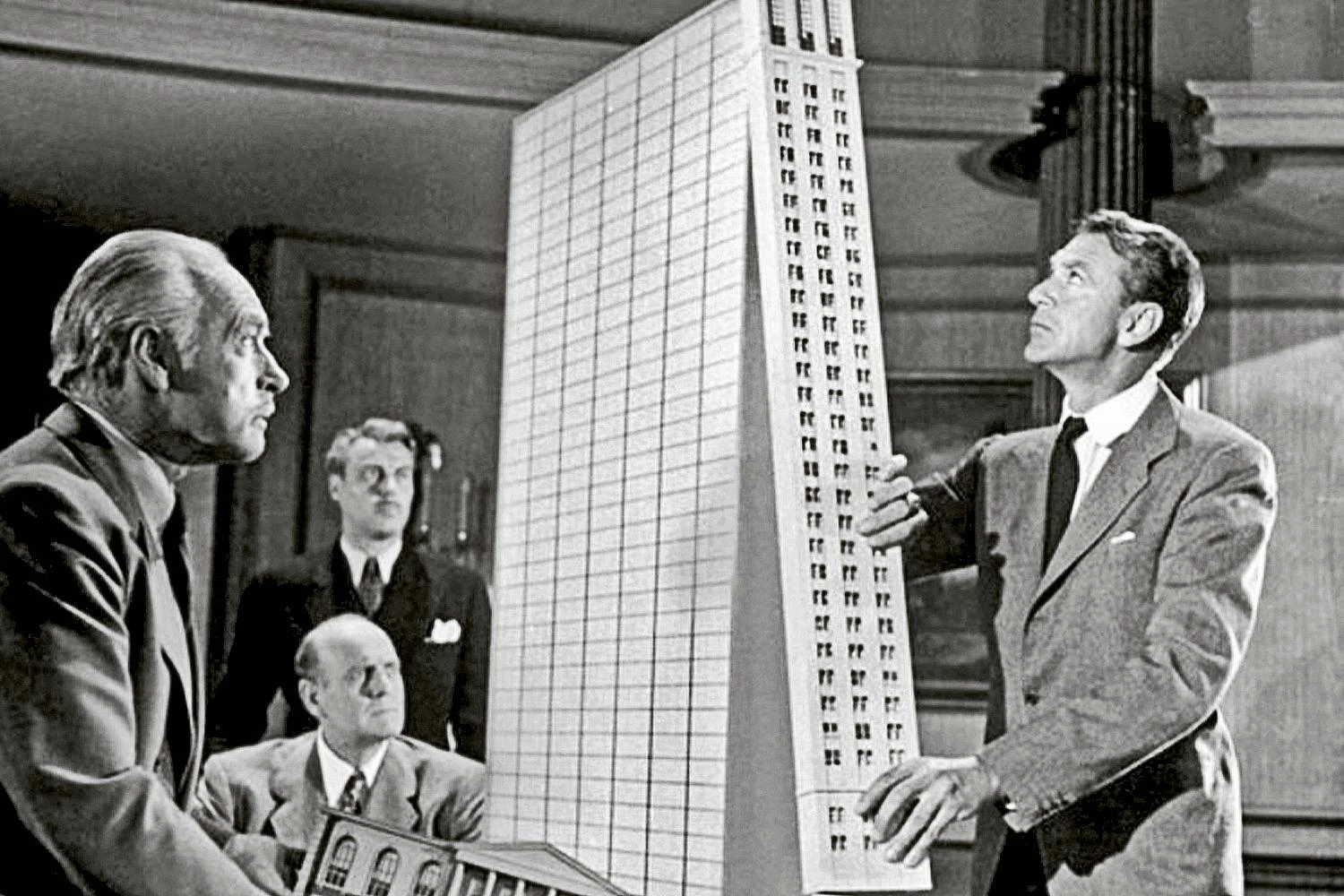

She was not fully satisfied, however, with the film that King Vidor directed, much as it has reaped a degree of success and popularity that has come down to our days, among architects of course but also among broader audiences. The movie is after all a love story in the world of architecture, ending with a trial of the kind that is frequent in American cinematography, and its protagonist is vaguely modeled on the titanic figure of Frank Lloyd Wright – who precisely in a law court described himself as the world’s best architect, justifying his lack of modesty by saying he had to tell the truth because he was under oath! – although many of the architectural models that appear are more in the language of Mies van der Rohe. Many architects have chosen their profession thanks to the fascination that Rand’s hero, Howard Roark, held for them, and yet his figure represents values opposed to those that ought to guide the practice of architecture, based as it should be on serving others more than on the pursuit of personal agendas. This paradox is explained in the memoirs of Moshe Safdie, the architect of Habitat 67 in Montreal, and I quote him in full:

“Every architect of my generation has had what I think of as an ‘Ayn Rand moment’ – the moment when one thinks of the architect as a self-assertive individual and an all-powerful creator with a singular grasp on Truth. I read Rand’s 1945 novel The Fountainhead very early in my time at McGill and recall absorbing it with great excitement. The architect in the book, Howard Roark, Rand’s Nietzschean hero, was briefly my idol. Gary Cooper’s portrayal of him in the movie only reinforced my enthusiasm, though I couldn’t quite see myself in Gary Cooper’s image. The enthusiasm was short-lived, at least in my case.

I came to appreciate that Roark was a self-obsessed narcissist, motivated by nothing noble. My ideal of an architect became Roark’s antithesis. Architecture is a mission, and an architect has a responsibility (to clients, to society) that transcends the self.”

Safdie’s reflection is probably shared by most architects. We still show the film in the schools and warn our students about Roark’s visionary individualism, but we cannot help but relish the lampooning of the critic Ellsworth M. Toohey, a character modeled on Harold Laski, or the demonization of the media magnate Gail Wynand, himself based on the mythical figure of William Randolph Hearst, who as we well know was also portrayed in Citizen Kane, Orson Welles’s masterpiece. There are scenes that now shock us, such as the violence of the first relationship of Roark and Dominique, but Rand knew about using scandal to make her books more popular, and people’s perception of relations between the sexes has changed much over the 80 years that have passed since the book was published. The philosopher, who took a break from her work in the film industry to take a secretarial position in an architecture practice and thus gain insight for the novel, filled The Fountainhead with her most extreme expression of the libertarian creed, her defense of sensual egocentrism against consensual capitalism, and her determined pursuit of freedom, the beacon of her life since her decision, at 21 years of age, to change her name and her country.

The Filmoteca Española presented a series of motion pictures about the fine arts. Architecture was represented by The Fountainhead (King Vidor, 1949), with a talk by Luis Fernández-Galiano.