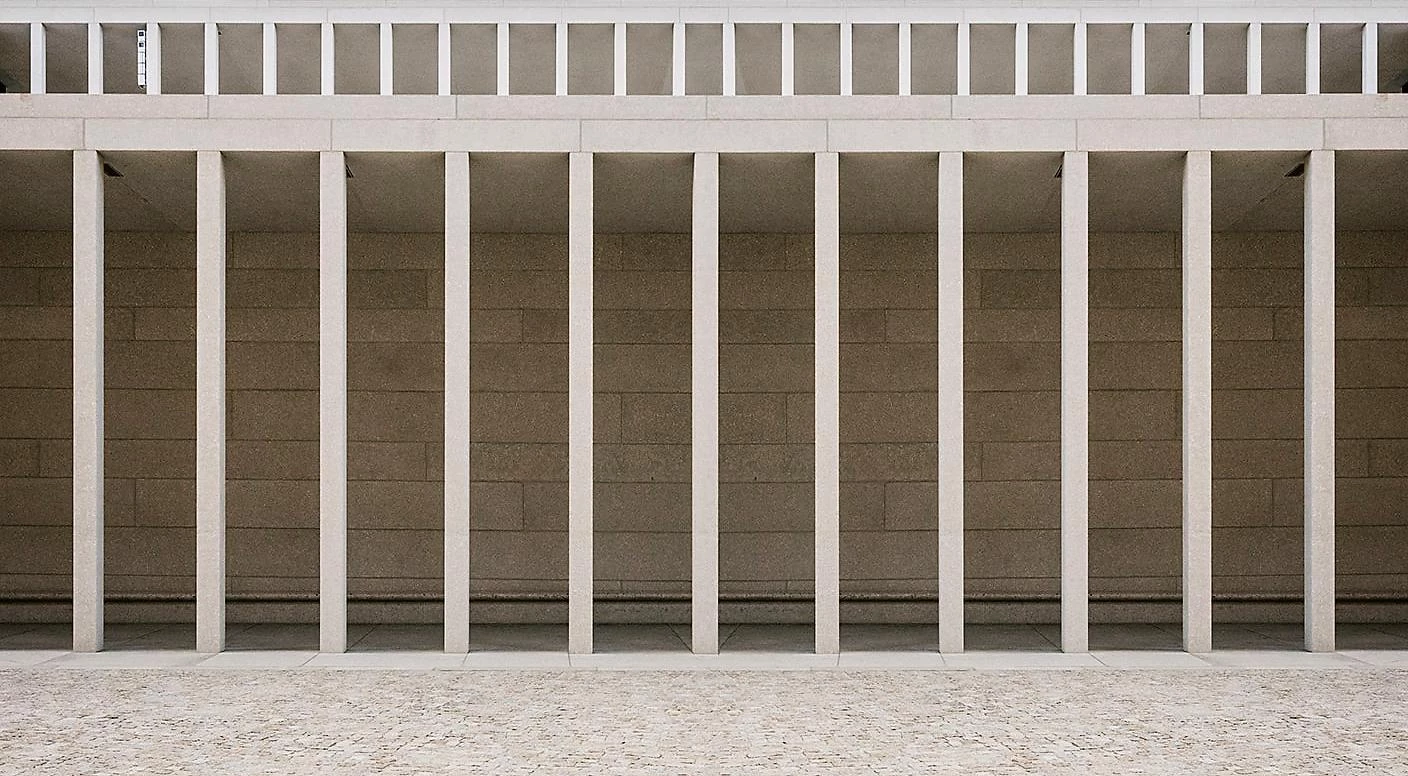

Museum of Modern Literature, 2002-2006, Marbach am Neckar (Germany)

David Chipperfield has a disciplined heart. Like Charles Dickens’ almost homonymous character, he tenaciously strives to temper his sensibility with rigour; however, unlike David Copperfield, the architect has disciplined his heart from the beginning of his professional Bildungsroman. Associated in his first London ventures with the gallery and magazine 9H, located in the same building as his studio then – its name referring to the hardest pencil lead – Chipperfield became known in the mid-eighties with a boutique for Issey Miyake on Sloane Street, which combined the tactile sensuality of the materials with its geometry’s disciplined refinement. In those times of historicist, postmodern fervour, fashion allowed space for dissent. Young Chipperfield, who studied at the experimental Architectural Association and was marked by the technological refinement of Rogers’ and Foster’s studios, made the Issey Miyake shop a manifesto for Miesian resistance.

In those days even his mentors were finding difficulty in being accepted in London: Rogers publicly rebuffed Prince Charles’ influential traditionalism, while Foster celebrated the creation of a small store for Katharine Hamnett on Brompton Road in Knightsbridge as a success. However, Chipperfield was fortunate to be commissioned for a series of projects during the Japanese real estate bubble, and in the eighties/nineties transition he erected three buildings that follow Tadao Ando’s formal trail and draw on materials such as concrete to express the urban and architectural continuity between what is present and the new, a feature that has doggedly characterised his work since.

This temperate fusion of tradition and innovation – together with the influence of the Italian Tendenza’s fundamentalism and vernacular inspiration – is magnificently expressed in the River & Rowing Museum, made up of two large sheds raised on stilts by the bank of the River Thames, recalling, in their exquisitely elementary forms, materials and details, Oxfordshire’s traditional barns. Its completion in 1997 was highlighted by a host of distinctions. It is made even more manifest in his own holiday house on the Atlantic coast in Galicia. Work on the latter started around the same time and the building was equally lauded with awards after its completion. In this house, genial nods to the Portuguese master Álvaro Siza merge naturally with the seafront of a small fishing village to create enclosures that are minute in their exact dimensions, yet infinite in generous views at the service of family life by the ocean. However, 1997 would prove decisive for the architect’s trajectory because of his triumph in the international competition for the restoration of the Neues Museum in Berlin. This commission would establish intimate bonds between him and that city, as well as with Germany itself.

Chipperfield had already built a brick family house in Berlin that was a sophisticated tribute to Mies’s late 1920s Esters and Lange Houses, but the Neues Museum was an undertaking of a completely different scale and complexity. Originally built in the mid-nineteenth century in Berlin’s Museum Island by a disciple of Schinkel, and partially destroyed during World War II, its restoration posed methodological and political problems, not to mention sentimental and symbolic ones, that Chipperfield addressed not only by drawing on architecture’s disciplinary foundations but also on technical procedures only previously applied to the restoration of works of art. To reconstruct a building the way you would restore a painting is certainly a slow, laborious and costly endeavour; nevertheless, the acclaim by critic and public alike that hailed its completion in 2009 clearly showed that it was well worth the effort. The German people had recovered an emblematic building, enriched by the traces of time and the scars of historical catastrophes, and the architect had conceived a new method for heritage intervention that has made this project his most celebrated to date.

During the twelve years he devoted to the Neues Museum project, Chipperfield increased his presence in Germany with corporate, commercial and institutional buildings such as the Ernsting Service Centre, a solid yet light structure in precast concrete almost Swiss-like in its succinctness; the Empire Riverside Hotel, a subtly articulated tower in Hamburg’s harbour front; and the Museum of Modern Literature in Marbach, Friedrich Schiller’s birthplace, with monumental porticoes incorporating the landscape into its muted classicism, a remarkable adaptation of character that earned the museum the Stirling Prize. Also in Berlin, and just opposite the Neues, across the canal surrounding Museum Island, he has built an imposing art gallery with warm materials and a provokingly abstract façade composition. Its large windows offer views of the new front for the museum complex, with the large portico, also designed by Chipperfield, which runs parallel to the canal and contains the new organisation of accesses and services; all of it in the Museum of Modern Literature’s refined classicist language, that merges seamlessly with Berlin’s massive nineteen century buildings and shapes a disciplined and exciting landscape.

Now a global architect, David Chipperfield has had the opportunity to build in different countries. In Italy he has worked in locations as unique as the Venetian Lagoon, where he has extended the dreamlike landscape of San Michele’s historic cemetery by means of severe courtyards and porticoes, or as complex as the periphery of Salerno, where he has erected a Palace of Justice in precast concrete and terracotta aggregate made up of interlocking volumes. In the United States he has finished two buildings in Iowa and a reflective extension to the Anchorage Museum which houses the Arctic Studies Center in Alaska’s largest city. Chipperfield’s creations have reached even China, with the Liangzhu Museum in Hangzhou – four bare travertine prisms that hold the extraordinary jade pieces produced by this Neolithic culture – and the unusual Ninetree Village residential complex, a luxury condominium supported by an elegant layout of load-bearing walls, enclosed by a vibrant façade of wooden slats, adapted to the topography of a small valley surrounded by bamboo forests.

This itinerary also includes Spain, the scene of his family holidays, where he has completed a series of works such as the Villaverde social housing in southern Madrid, a sculptural piece of random rhythm and intense chromaticism, redeeming the predictable with a determined plasticity; the splendid and at the same time succinct refurbishment of the Paseo del Óvalo in Teruel, with its great stone carpet and the large corten steel gate leading to the lifts built in the escarpment that enable the mechanical connection between the railway station of the lower city and the medieval centre upon the cliff; the colossal City of Justice in Barcelona, where he has pushed the ideas tested in Salerno to an extreme in order to arrange an extraordinary still life of impassive prisms that combine the disciplined regularity of the openings with Morandi’s delicate sandy palette; or the ‘Veles e Vents’ building in Valencia, which provided quarters and grandstands for the 2007 America’s Cup, a series of cantilevered floor slabs of precise regularity and Mediterranean whiteness projected over the port and sailing boats.

In the end this conspicuously extraterritorial Englishman has also been accepted in his home country. The meticulous industrial anonymity of Gormley’s studio in London, and the terraced spatial richness of the prism erected in Glasgow for the BBC Scotland Headquarters were followed by recognition: in 2008 Chipperfield was made a Royal Academician; he was knighted in 2010 and was awarded the RIBA Gold Medal in 2011. Also in 2011 he finalised two small museums related to British artists – the Hepworth Wakefield gallery in Yorkshire and the one dedicated to William Turner in Kent – and received the Mies Award for the Neues Museum. In 2012 he directed the Architecture Exhibition of the Venice Biennale, and in 2013 was awarded the Praemium Imperiale, but we have had to wait until 2023 for the Pritzker Prize to celebrate his exceptional career. The extra hard lead pencil has come a long way and the disciplined heart of this Englishman, which is now partly German and a great deal Latino – married as he is to a warm and outgoing Argentinian – runs studios in London, Berlin, Milan and Shanghai with projects all over the world. His architectural practice operates masterfully within the limits imposed by continuity: the continuity of built environments, but also the continuity of people’s lives.

James-Simon-Galerie, 1999-2018, Berlin (Germany). Photo: Celia Uhalde